Deep Dive into Virtual File Systems: Architecture, Implementation, and Practice

A comprehensive exploration of Virtual File System (VFS) architecture and implementation, covering design principles, kernel integration, and practical file system development.

Introduction

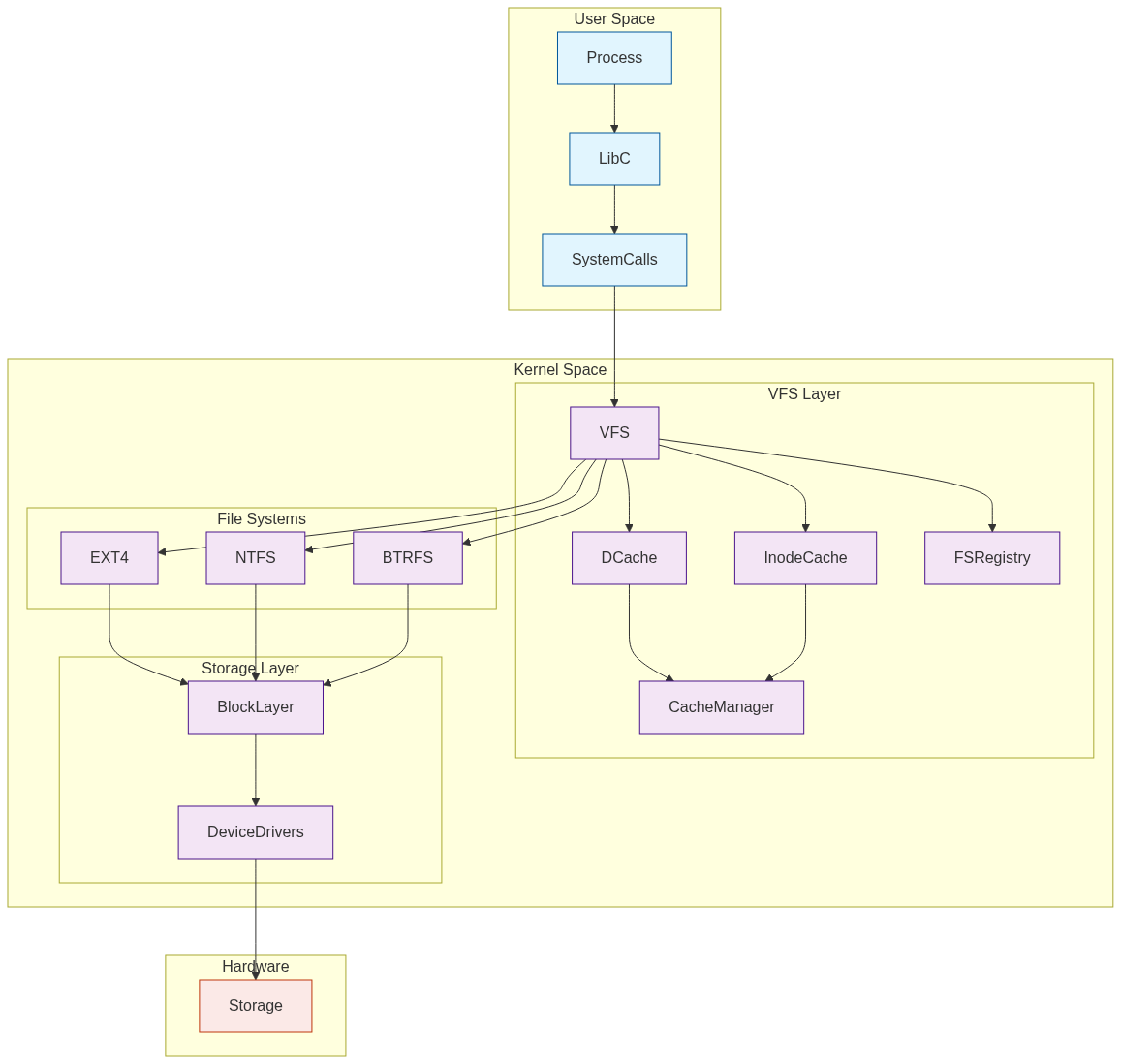

The Virtual File System (VFS) serves as a crucial abstraction layer in modern operating systems, providing a unified interface between user processes and various file systems. This article explores the intricate details of VFS implementation, its evolution, and practical applications in system programming.

VFS Architecture

The Abstract Layer

At its core, VFS operates as an abstraction layer that standardizes how different file systems interact with the kernel. This design pattern emerged from the need to support multiple file systems concurrently while maintaining a consistent interface for processes.

The VFS layer implements several key abstractions:

- File Objects: Represent open files within a process

- Inodes: Store metadata about files

- Directory Entries: Cache filesystem hierarchy

- Superblocks: Maintain mounted filesystem information

System Call Interface

Let’s implement a basic system call wrapper to demonstrate how processes interact with VFS:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

#include <stdio.h>

#include <fcntl.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <errno.h>

typedef struct {

int fd;

char *path;

mode_t mode;

} file_ops_t;

int vfs_open_file(file_ops_t *ops) {

if (!ops || !ops->path) {

errno = EINVAL;

return -1;

}

ops->fd = open(ops->path, O_RDWR | O_CREAT, ops->mode);

if (ops->fd < 0) {

perror("Failed to open file");

return -1;

}

return ops->fd;

}

int vfs_close_file(file_ops_t *ops) {

if (!ops || ops->fd < 0) {

errno = EINVAL;

return -1;

}

if (close(ops->fd) < 0) {

perror("Failed to close file");

return -1;

}

return 0;

}

int main(void) {

file_ops_t ops = {

.fd = -1,

.path = "/tmp/test_file",

.mode = 0644

};

if (vfs_open_file(&ops) < 0) {

return 1;

}

printf("Successfully opened file with fd: %d\n", ops.fd);

if (vfs_close_file(&ops) < 0) {

return 1;

}

printf("Successfully closed file\n");

return 0;

}

To compile and run this code:

1

2

gcc -Wall -Wextra -o vfs_demo vfs_demo.c

./vfs_demo

The assembly output for the main function (x86_64) reveals interesting details about system call handling:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

main:

push rbp

mov rbp, rsp

sub rsp, 32

mov DWORD PTR [rbp-20], -1

mov QWORD PTR [rbp-16], OFFSET FLAT:.LC0

mov DWORD PTR [rbp-8], 420

lea rax, [rbp-20]

mov rdi, rax

call vfs_open_file

Core Components

Directory Entry Cache (dcache)

The directory entry cache is a crucial performance optimization in VFS. Let’s implement a simple dcache simulator:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

#define MAX_PATH_LEN 256

#define CACHE_SIZE 1024

typedef struct dentry {

char name[MAX_PATH_LEN];

struct dentry *parent;

unsigned long inode_ptr;

struct dentry *next;

} dentry_t;

typedef struct {

dentry_t *entries[CACHE_SIZE];

size_t count;

} dcache_t;

dcache_t *dcache_create(void) {

dcache_t *cache = calloc(1, sizeof(dcache_t));

if (!cache) {

return NULL;

}

return cache;

}

unsigned long hash_path(const char *path) {

unsigned long hash = 5381;

int c;

while ((c = *path++)) {

hash = ((hash << 5) + hash) + c;

}

return hash % CACHE_SIZE;

}

int dcache_add(dcache_t *cache, const char *path, unsigned long inode) {

if (!cache || !path) {

return -1;

}

unsigned long hash = hash_path(path);

dentry_t *entry = malloc(sizeof(dentry_t));

if (!entry) {

return -1;

}

strncpy(entry->name, path, MAX_PATH_LEN - 1);

entry->name[MAX_PATH_LEN - 1] = '\0';

entry->inode_ptr = inode;

entry->parent = NULL;

entry->next = cache->entries[hash];

cache->entries[hash] = entry;

cache->count++;

return 0;

}

dentry_t *dcache_lookup(dcache_t *cache, const char *path) {

if (!cache || !path) {

return NULL;

}

unsigned long hash = hash_path(path);

dentry_t *current = cache->entries[hash];

while (current) {

if (strcmp(current->name, path) == 0) {

return current;

}

current = current->next;

}

return NULL;

}

void dcache_destroy(dcache_t *cache) {

if (!cache) {

return;

}

for (size_t i = 0; i < CACHE_SIZE; i++) {

dentry_t *current = cache->entries[i];

while (current) {

dentry_t *next = current->next;

free(current);

current = next;

}

}

free(cache);

}

int main(void) {

dcache_t *cache = dcache_create();

if (!cache) {

fprintf(stderr, "Failed to create dcache\n");

return 1;

}

// Add some entries

dcache_add(cache, "/usr/bin/python", 12345);

dcache_add(cache, "/etc/passwd", 67890);

// Lookup test

dentry_t *entry = dcache_lookup(cache, "/etc/passwd");

if (entry) {

printf("Found entry: %s with inode: %lu\n",

entry->name, entry->inode_ptr);

}

dcache_destroy(cache);

return 0;

}

To compile and run:

1

2

gcc -Wall -Wextra -o dcache_demo dcache_demo.c

./dcache_demo

Inode Cache

The inode cache maintains frequently accessed file metadata. Here’s a simplified implementation:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <time.h>

typedef struct {

unsigned long inode_number;

mode_t mode;

uid_t uid;

gid_t gid;

time_t atime;

time_t mtime;

time_t ctime;

size_t size;

unsigned long blocks;

} inode_t;

typedef struct inode_cache_entry {

inode_t inode;

struct inode_cache_entry *next;

int ref_count;

} inode_cache_entry_t;

typedef struct {

inode_cache_entry_t **buckets;

size_t size;

} inode_cache_t;

inode_cache_t *create_inode_cache(size_t size) {

inode_cache_t *cache = malloc(sizeof(inode_cache_t));

if (!cache) {

return NULL;

}

cache->buckets = calloc(size, sizeof(inode_cache_entry_t*));

if (!cache->buckets) {

free(cache);

return NULL;

}

cache->size = size;

return cache;

}

unsigned long hash_inode(unsigned long inode_number, size_t size) {

return inode_number % size;

}

int cache_inode(inode_cache_t *cache, inode_t *inode) {

if (!cache || !inode) {

return -1;

}

unsigned long hash = hash_inode(inode->inode_number, cache->size);

inode_cache_entry_t *entry = malloc(sizeof(inode_cache_entry_t));

if (!entry) {

return -1;

}

entry->inode = *inode;

entry->ref_count = 1;

entry->next = cache->buckets[hash];

cache->buckets[hash] = entry;

return 0;

}

inode_t *lookup_inode(inode_cache_t *cache, unsigned long inode_number) {

if (!cache) {

return NULL;

}

unsigned long hash = hash_inode(inode_number, cache->size);

inode_cache_entry_t *entry = cache->buckets[hash];

while (entry) {

if (entry->inode.inode_number == inode_number) {

entry->ref_count++;

return &entry->inode;

}

entry = entry->next;

}

return NULL;

}

void destroy_inode_cache(inode_cache_t *cache) {

if (!cache) {

return;

}

for (size_t i = 0; i < cache->size; i++) {

inode_cache_entry_t *current = cache->buckets[i];

while (current) {

inode_cache_entry_t *next = current->next;

free(current);

current = next;

}

}

free(cache->buckets);

free(cache);

}

Implementation Details

The VFS implementation in the Linux kernel involves several key data structures and mechanisms that work together to provide a seamless file system abstraction. Understanding these implementation details is crucial for kernel developers and system programmers working with file systems.

VFS Data Structures

The core VFS implementation relies on several key data structures:

- struct super_block: Represents a mounted file system

- struct inode: Represents a file or directory

- struct dentry: Represents a directory entry

- struct file: Represents an open file

File Operation Tables

VFS uses function pointers to delegate operations to specific file systems:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

struct file_operations {

loff_t (*llseek) (struct file *, loff_t, int);

ssize_t (*read) (struct file *, char __user *, size_t, loff_t *);

ssize_t (*write) (struct file *, const char __user *, size_t, loff_t *);

int (*open) (struct inode *, struct file *);

int (*release) (struct inode *, struct file *);

// ... more operations

};

Practical Examples

Let’s explore practical examples of VFS usage and implementation:

Example 1: Simple File System Implementation

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

#include <linux/fs.h>

#include <linux/module.h>

static struct super_operations simple_super_ops = {

.drop_inode = generic_drop_inode,

};

static int simple_fill_super(struct super_block *sb, void *data, int silent) {

struct inode *root_inode;

sb->s_blocksize = PAGE_SIZE;

sb->s_blocksize_bits = PAGE_SHIFT;

sb->s_magic = 0x73696d70; /* "simp" */

sb->s_op = &simple_super_ops;

root_inode = new_inode(sb);

if (!root_inode)

return -ENOMEM;

root_inode->i_ino = 1;

root_inode->i_mode = S_IFDIR | 0755;

root_inode->i_op = &simple_dir_inode_operations;

root_inode->i_fop = &simple_dir_operations;

sb->s_root = d_make_root(root_inode);

if (!sb->s_root)

return -ENOMEM;

return 0;

}

Example 2: VFS Integration Points

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

// File system registration

static struct file_system_type simple_fs_type = {

.owner = THIS_MODULE,

.name = "simplefs",

.mount = simple_mount,

.kill_sb = kill_block_super,

};

// Mount function

static struct dentry *simple_mount(struct file_system_type *fs_type,

int flags, const char *dev_name,

void *data) {

return mount_bdev(fs_type, flags, dev_name, data, simple_fill_super);

}

Advanced Concepts

File System Registration

Modern VFS implementations maintain a registry of supported file systems. Here’s a simplified version:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

#define MAX_FS_NAME 32

typedef struct filesystem_ops {

int (*mount)(const char *source, const char *target);

int (*unmount)(const char *target);

int (*read)(const char *path, char *buffer, size_t size);

int (*write)(const char *path, const char *buffer, size_t size);

} filesystem_ops_t;

typedef struct filesystem_type {

char name[MAX_FS_NAME];

filesystem_ops_t ops;

struct filesystem_type *next;

} filesystem_type_t;

typedef struct {

filesystem_type_t *head;

size_t count;

} filesystem_registry_t;

filesystem_registry_t *create_fs_registry(void) {

filesystem_registry_t *registry = malloc(sizeof(filesystem_registry_t));

if (!registry) {

return NULL;

}

registry->head = NULL;

registry->count = 0;

return registry;

}

int register_filesystem(filesystem_registry_t *registry,

const char *name,

filesystem_ops_t *ops) {

if (!registry || !name || !ops) {

return -1;

}

filesystem_type_t *fs_type = malloc(sizeof(filesystem_type_t));

if (!fs_type) {

return -1;

}

strncpy(fs_type->name, name, MAX_FS_NAME - 1);

fs_type->name[MAX_FS_NAME - 1] = '\0';

fs_type->ops = *ops;

fs_type->next = registry->head;

registry->head = fs_type;

registry->count++;

return 0;

}

filesystem_type_t *lookup_filesystem(filesystem_registry_t *registry,

const char *name) {

if (!registry || !name) {

return NULL;

}

filesystem_type_t *current = registry->head;

while (current) {

if (strcmp(current->name, name) == 0) {

return current;

}

current = current->next;

}

return NULL;

}

void destroy_fs_registry(filesystem_registry_t *registry) {

if (!registry) {

return;

}

filesystem_type_t *current = registry->head;

while (current) {

filesystem_type_t *next = current->next;

free(current);

current = next;

}

free(registry);

}

System Architecture

The VFS system architecture provides a layered approach to file system management, with each layer serving a specific purpose in the overall design.

Architectural Layers

- User Space Interface Layer

- System call interface (open, read, write, close)

- Library functions (fopen, fread, fwrite, fclose)

- Application-level file operations

- VFS Abstraction Layer

- Unified file system interface

- Path resolution and namespace management

- Permission checking and security

- Caching and buffering

- File System Implementation Layer

- Specific file system drivers (ext4, XFS, Btrfs)

- Format-specific operations

- Metadata management

- Storage allocation

- Block Device Layer

- I/O scheduling and queuing

- Device drivers

- Hardware abstraction

Interaction Flow

The typical flow of a file operation through the VFS architecture:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

User Application

↓

System Call Interface

↓

VFS Layer (path resolution, permission checking)

↓

File System Specific Operations

↓

Block Device Layer

↓

Hardware Storage

This layered architecture ensures that applications can work with any file system through a consistent interface while allowing file systems to implement their specific optimizations and features.

Conclusion

Understanding VFS architecture is crucial for system programmers and anyone working with file systems at a low level. The abstractions provided by VFS enable the development of filesystem-agnostic applications while maintaining performance through sophisticated caching mechanisms. Further Reading

- Advanced Operating Systems and Implementation

- Linux Kernel Development (3rd Edition)

- Understanding the Linux Virtual File System

- Operating Systems: Three Easy Pieces - File Systems Chapter

References

- The Linux Programming Interface

- Linux System Programming

- Understanding the Linux Kernel

- Advanced Linux Programming

NOTE: This article provides a simplified view of VFS for educational purposes. Production implementations include additional complexity and optimizations.