Everything About Memory Allocators: Write a Simple Memory Allocator

A comprehensive guide to memory allocators, covering allocation strategies, heap management, and implementing a custom memory allocator from scratch with performance considerations.

Introduction

Memory allocation is a fundamental aspect of systems programming that every developer should understand. This article provides an in-depth exploration of implementing a basic memory allocator in C, covering malloc(), free(), calloc(), and realloc(). While our implementation won’t match the sophistication of production allocators like ptmalloc or jemalloc, it will help you understand the core concepts.

Memory Layout Fundamentals

Before diving into implementation details, let’s understand how memory is organized in a Linux process. A program’s virtual address space typically consists of several segments:

- Text Segment (Code Segment)

- Contains executable instructions

- Read-only

- Shared among processes running the same program

- Data Segment

- Contains initialized global and static variables

- Split into read-only and read-write sections

- BSS (Block Started by Symbol)

- Contains uninitialized global and static variables

- Automatically initialized to zero by the kernel

- Takes no actual space in the executable file

- Heap

- Dynamically allocated memory

- Grows upward (toward higher addresses)

- Managed by malloc/free

- Starts after BSS

- Stack

- Automatic variables

- Function call frames

- Grows downward (toward lower addresses)

- Automatically managed

The program break (brk) marks the end of the heap segment. Our memory allocator will primarily interact with this boundary using the sbrk() system call.

Memory Management Basics

The Program Break

The program break is a virtual address that marks the end of the process’s data segment. We can manipulate it using two system calls:

- brk(void *addr) - Sets the program break to a specific address

- sbrk(intptr_t increment) - Adjusts the program break by a specified increment

Key points about sbrk():

- sbrk(0) returns the current program break address

- sbrk(positive_value) increases heap size

- sbrk(negative_value) decreases heap size

- Returns (void*)-1 on error

Building a Memory Allocator

Core Data Structures

Our allocator needs to track allocated memory blocks. We’ll use a linked list approach with each block containing a header structure.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

typedef char ALIGN[16];

union header {

struct {

size_t size; // Size of the block

unsigned is_free; // Block status flag

union header *next; // Next block in list

} s;

ALIGN stub; // Force 16-byte alignment

};

typedef union header header_t;

// Global variables

header_t *head = NULL, *tail = NULL;

pthread_mutex_t global_malloc_lock;

The header structure serves several purposes:

- Tracks block size

- Maintains free/allocated status

- Links blocks together

- Ensures proper memory alignment

Memory Block Headers

Each allocated block needs a header to store metadata:

1

2

3

4

5

6

typedef struct block_header {

size_t size; // Size of the block (including header)

int is_free; // 1 if free, 0 if allocated

struct block_header* next; // Pointer to next block

struct block_header* prev; // Pointer to previous block

} block_header_t;

The header contains:

- size: Total size including the header

- is_free: Flag indicating if the block is available

- next/prev: Pointers for maintaining a doubly-linked list

Implementation Details

The memory allocator implementation involves several key design decisions and optimizations:

Block Alignment

All memory blocks must be aligned to word boundaries for optimal performance:

1

2

#define ALIGNMENT 8

#define ALIGN(size) (((size) + (ALIGNMENT-1)) & ~(ALIGNMENT-1))

Block Splitting and Coalescing

When allocating memory, we may need to split large blocks:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

static block_header_t* split_block(block_header_t* block, size_t size) {

if (block->size >= size + sizeof(block_header_t) + ALIGNMENT) {

block_header_t* new_block = (block_header_t*)((char*)block + size);

new_block->size = block->size - size;

new_block->is_free = 1;

new_block->next = block->next;

new_block->prev = block;

if (block->next) {

block->next->prev = new_block;

}

block->next = new_block;

block->size = size;

return new_block;

}

return NULL;

}

Memory Coalescing

When freeing blocks, adjacent free blocks should be merged:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

static void coalesce_blocks(block_header_t* block) {

// Merge with next block if free

if (block->next && block->next->is_free) {

block->size += block->next->size;

block->next = block->next->next;

if (block->next) {

block->next->prev = block;

}

}

// Merge with previous block if free

if (block->prev && block->prev->is_free) {

block->prev->size += block->size;

block->prev->next = block->next;

if (block->next) {

block->next->prev = block->prev;

}

}

}

Core Functions Implementation

malloc()

The malloc() implementation follows these steps:

- Check for valid size request

- Look for existing free block of sufficient size

- If found, mark as used and return

- If not found, request new memory from OS

- Setup header and return pointer

Here’s the implementation:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

void *malloc(size_t size) {

if (!size) return NULL;

pthread_mutex_lock(&global_malloc_lock);

// Try to find a free block

header_t *header = get_free_block(size);

if (header) {

header->s.is_free = 0;

pthread_mutex_unlock(&global_malloc_lock);

return (void*)(header + 1);

}

// Need new block from OS

size_t total_size = sizeof(header_t) + size;

void *block = sbrk(total_size);

if (block == (void*)-1) {

pthread_mutex_unlock(&global_malloc_lock);

return NULL;

}

// Initialize new block

header = block;

header->s.size = size;

header->s.is_free = 0;

header->s.next = NULL;

// Update list pointers

if (!head) head = header;

if (tail) tail->s.next = header;

tail = header;

pthread_mutex_unlock(&global_malloc_lock);

return (void*)(header + 1);

}

free()

The free() implementation handles memory deallocation:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

void free(void *block) {

if (!block) return;

pthread_mutex_lock(&global_malloc_lock);

header_t *header = (header_t*)block - 1;

void *programbreak = sbrk(0);

// Check if block is at the end of heap

if ((char*)block + header->s.size == programbreak) {

// Remove from list

if (head == tail) {

head = tail = NULL;

} else {

header_t *tmp = head;

while (tmp) {

if (tmp->s.next == tail) {

tmp->s.next = NULL;

tail = tmp;

break;

}

tmp = tmp->s.next;

}

}

// Return memory to OS

sbrk(0 - sizeof(header_t) - header->s.size);

} else {

// Mark block as free

header->s.is_free = 1;

}

pthread_mutex_unlock(&global_malloc_lock);

}

calloc()

calloc() allocates memory and initializes it to zero:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

void *calloc(size_t num, size_t nsize) {

size_t size;

void *block;

if (!num || !nsize) return NULL;

size = num * nsize;

// Check for multiplication overflow

if (nsize != size / num) return NULL;

block = malloc(size);

if (!block) return NULL;

// Zero out the memory

memset(block, 0, size);

return block;

}

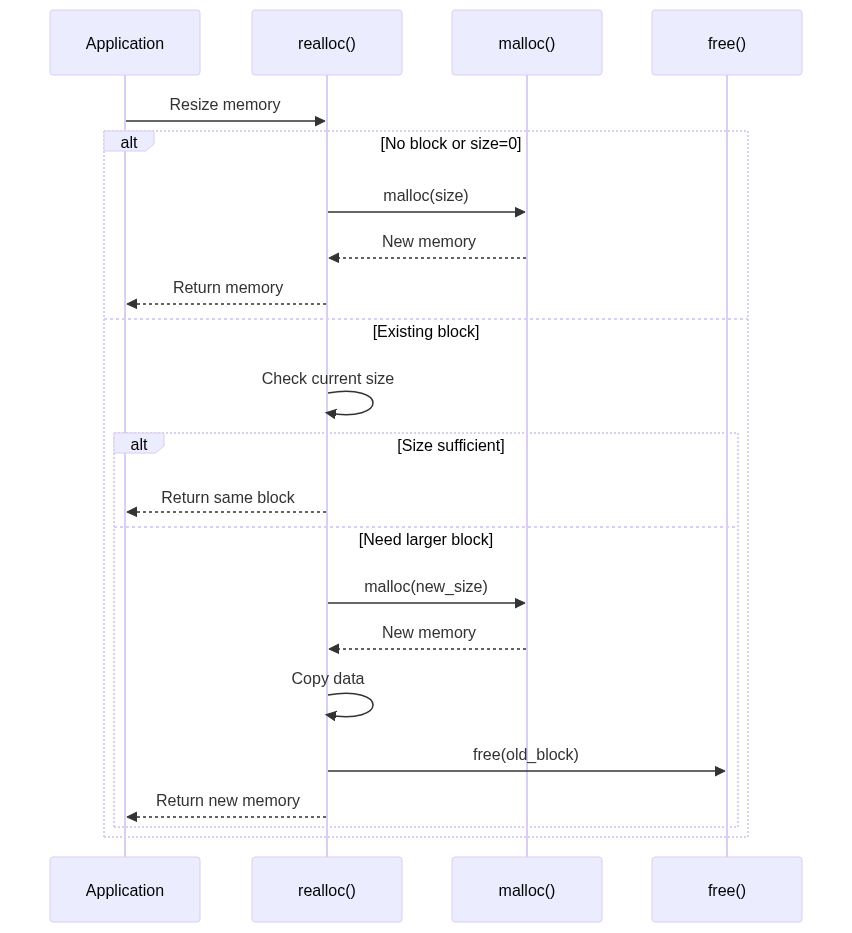

realloc()

realloc() changes the size of an existing allocation:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

void *realloc(void *block, size_t size) {

if (!block || !size) return malloc(size);

header_t *header = (header_t*)block - 1;

if (header->s.size >= size) return block;

void *ret = malloc(size);

if (ret) {

memcpy(ret, block, header->s.size);

free(block);

}

return ret;

}

Thread Safety Considerations

Our implementation uses a global mutex to ensure thread safety:

1

2

3

4

pthread_mutex_t global_malloc_lock;

// Initialize in main or constructor

pthread_mutex_init(&global_malloc_lock, NULL);

However, this approach has limitations:

- Single lock creates contention

- sbrk() isn’t thread-safe

- No protection against foreign sbrk() calls

Testing and Usage

Let’s test our allocator with a comprehensive example:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

int main() {

printf("Testing custom memory allocator\n");

// Test basic allocation

void* ptr1 = my_malloc(100);

printf("Allocated 100 bytes at %p\n", ptr1);

void* ptr2 = my_malloc(200);

printf("Allocated 200 bytes at %p\n", ptr2);

// Test freeing

my_free(ptr1);

printf("Freed first allocation\n");

// Test allocation after free (should reuse space)

void* ptr3 = my_malloc(50);

printf("Allocated 50 bytes at %p\n", ptr3);

// Test calloc

void* ptr4 = my_calloc(10, sizeof(int));

printf("Allocated zeroed array at %p\n", ptr4);

// Test realloc

ptr4 = my_realloc(ptr4, 20 * sizeof(int));

printf("Reallocated array to %p\n", ptr4);

// Cleanup

my_free(ptr2);

my_free(ptr3);

my_free(ptr4);

printf("All tests completed successfully\n");

return 0;

}

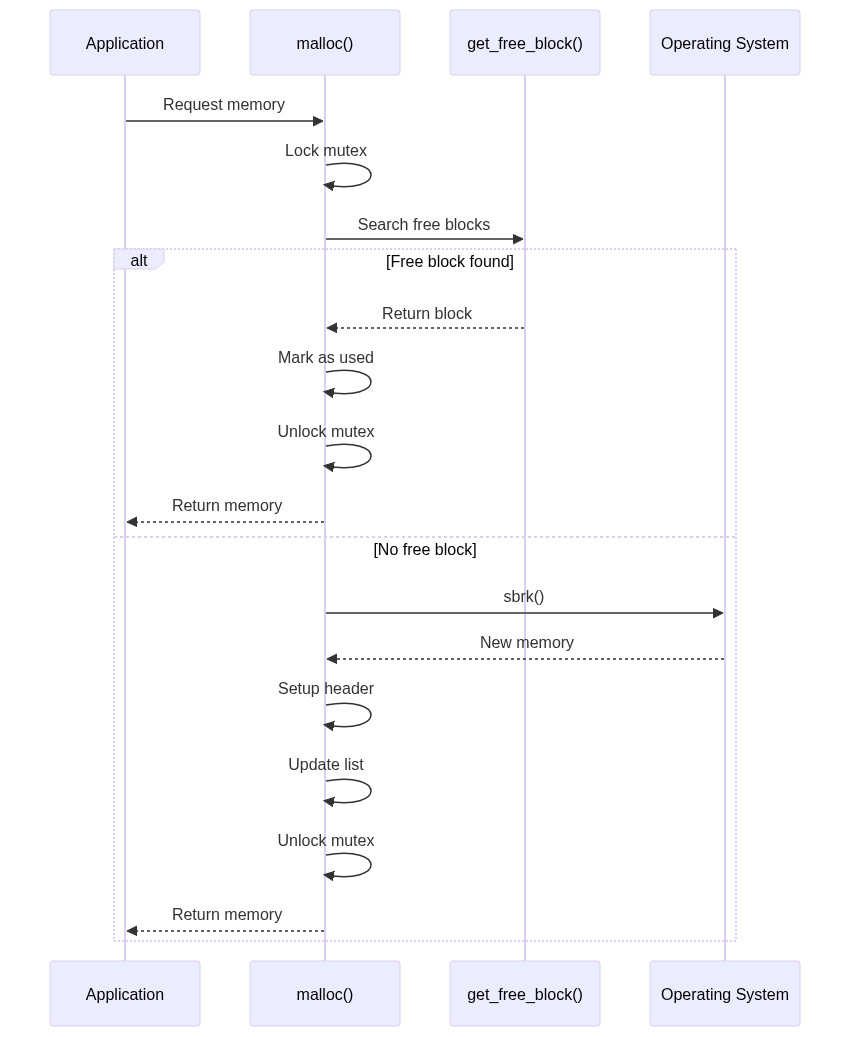

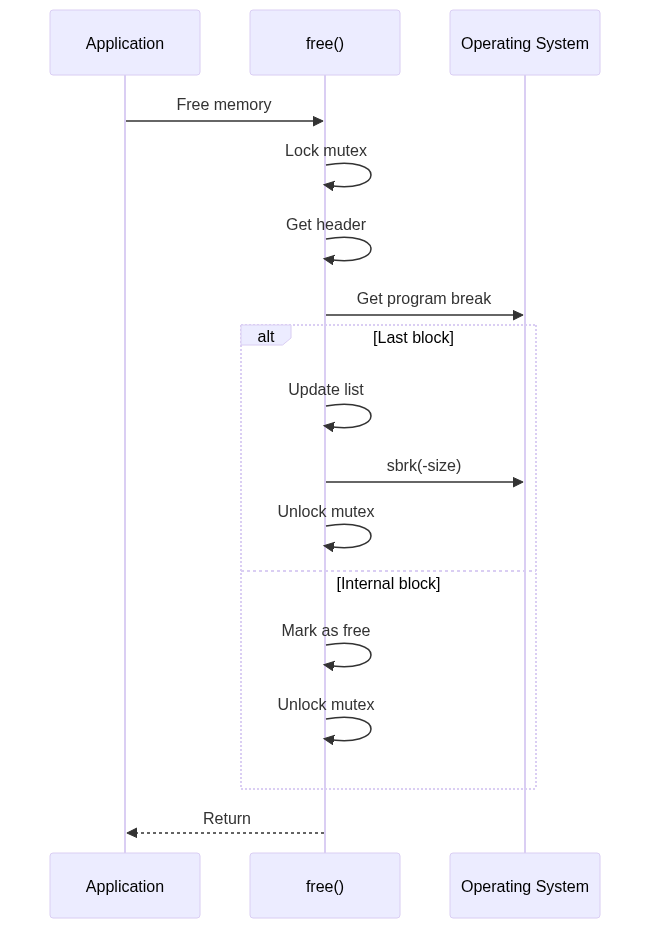

Sequence Diagrams

Understanding the flow of memory allocation operations is crucial. Here are sequence diagrams showing the interaction between different components:

malloc() Sequence

sequenceDiagram

participant App as Application

participant Malloc as my_malloc()

participant Heap as Heap Manager

participant OS as Operating System

App->>Malloc: Request memory (size)

Malloc->>Heap: Find suitable block

alt Block found

Heap->>Malloc: Return existing block

Malloc->>Heap: Split block if needed

else No block found

Malloc->>OS: Request more memory (sbrk)

OS->>Malloc: Extend heap

Malloc->>Heap: Create new block

end

Malloc->>App: Return pointer to allocated memory

free() Sequence

sequenceDiagram

participant App as Application

participant Free as my_free()

participant Heap as Heap Manager

App->>Free: Free memory (pointer)

Free->>Heap: Mark block as free

Free->>Heap: Check adjacent blocks

alt Adjacent blocks are free

Heap->>Free: Coalesce blocks

Free->>Heap: Update block list

end

Free->>App: Return (void)

Memory Layout Evolution

graph TD

A[Initial Heap] --> B[First malloc(100)]

B --> C[Second malloc(200)]

C --> D[free(first block)]

D --> E[malloc(50) - reuses space]

subgraph "Heap States"

A1["|------ Free Block ------|"]

B1["|Used(100)|-- Free --|"]

C1["|Used(100)|Used(200)|Free|"]

D1["|Free(100)|Used(200)|Free|"]

E1["|Used(50)|Free|Used(200)|Free|"]

end

This visualization shows how the heap evolves as allocations and deallocations occur, demonstrating block splitting, coalescing, and reuse.

Further Reading

- The Linux Programming Interface by Michael Kerrisk

- Advanced Programming in the UNIX Environment by W. Richard Stevens

- Understanding the Linux Virtual Memory Manager by Mel Gorman

- Doug Lea’s Memory Allocator Documentation

- jemalloc Documentation and Source Code

Conclusion

This implementation demonstrates the fundamental concepts of memory allocation while keeping things simple enough to understand. Production allocators add many optimizations:

- Multiple allocation strategies

- Memory pooling

- Thread-local caches

- Sophisticated fragmentation handling

- Memory mapping for large allocations

Key takeaways:

- Memory allocation involves both userspace and kernel space interaction

- Thread safety requires careful consideration

- Memory layout understanding is crucial

- Simple implementations help learn fundamentals

- Production allocators are much more complex

Remember that this implementation is for educational purposes. Production systems should use established allocators that have been thoroughly tested and optimized.