How PostgreSQL MVCC Works: Transaction Visibility, Garbage Collection, Hidden Columns to VACUUM

A deep dive into PostgreSQL's Multi-Version Concurrency Control (MVCC), exploring transaction visibility, garbage collection, and vacuum operations.

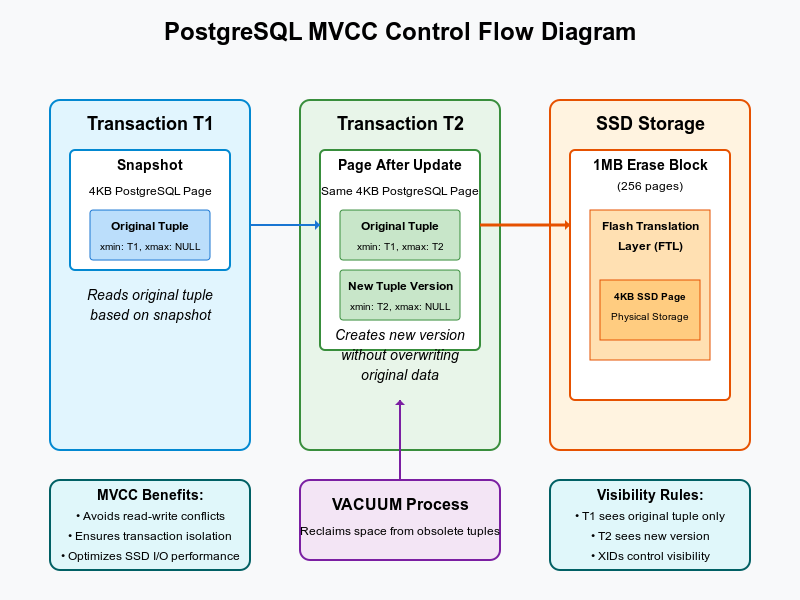

PostgreSQL’s Multi-Version Concurrency Control (MVCC) is one of the database’s most powerful features, enabling consistent views of data while maintaining high levels of concurrency. This blog post explores the inner workings of MVCC, examining how PostgreSQL manages multiple versions of rows, the hidden columns that track these versions, and the garbage collection mechanisms that keep the system efficient.

Introduction

Modern database systems must handle multiple concurrent transactions while maintaining data consistency. PostgreSQL solves this challenge through its MVCC implementation, which allows readers to see a consistent view of data without blocking writers, and vice versa.

Unlike traditional locking mechanisms, MVCC creates new versions of rows when data is modified, keeping the old versions available for transactions that might still need them. This approach offers several advantages:

- Readers don’t block writers

- Writers don’t block readers

- Each transaction sees a consistent snapshot of the database

Let’s explore how PostgreSQL implements this mechanism by examining its internal structures.

Hidden Columns in PostgreSQL

When you create a table in PostgreSQL, each row contains more information than just the columns you defined. PostgreSQL adds several hidden system columns to every row. These columns are not visible when you use SELECT *, but they are crucial for MVCC functionality.

Let’s start by creating a simple table to demonstrate these hidden columns:

1

2

3

4

5

6

CREATE TABLE account (

id INTEGER,

balance MONEY

);

INSERT INTO account VALUES (1, '$500');

Now let’s look at the standard way to query this table:

1

SELECT * FROM account;

This returns just the visible columns:

1

2

3

id | balance

----+---------

1 | $500.00

However, PostgreSQL stores several hidden columns with each row. We can access these using a special syntax:

1

2

SELECT ctid, xmin, xmax, *, tableoid, cmin, cmax

FROM account;

For our exploration, we’ll focus on three key hidden columns:

1

2

SELECT ctid, xmin, xmax, *

FROM account;

This might return something like:

1

2

3

ctid | xmin | xmax | id | balance

--------+------+------+----+---------

(0,1) | 755 | 0 | 1 | $500.00

Let’s examine these hidden columns:

ctid (Tuple ID): This is a physical location identifier for the row, represented as

(page,tuple). The first number indicates the page within the table, and the second number is the position within that page. This value can change during operations like VACUUM.xmin: The ID of the transaction that created this row version. It tells us which transaction inserted this particular version.

xmax: The ID of the transaction that deleted or updated this row version (creating a new version). A value of 0 means the row version is still “live” and visible to new transactions.

Seeing MVCC in Action

To understand how PostgreSQL uses these hidden columns for concurrency control, let’s run through some transactions and observe the changes:

First, let’s add a couple more accounts:

1

2

3

INSERT INTO account VALUES

(2, '$600'),

(3, '$700');

Now let’s query our table with the hidden columns:

1

2

SELECT ctid, xmin, xmax, *

FROM account;

This might give us:

1

2

3

4

5

ctid | xmin | xmax | id | balance

--------+------+------+----+---------

(0,1) | 755 | 0 | 1 | $500.00

(0,2) | 756 | 0 | 2 | $600.00

(0,3) | 756 | 0 | 3 | $700.00

Notice that accounts 2 and 3 have the same xmin value because they were created in the same transaction.

Updating a Row: Creating a New Version

Now let’s see what happens when we update a row. We’ll start a transaction and update the first account:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

BEGIN;

-- Check current transaction ID

SELECT txid_current();

-- Result: 757

-- Update the first account

UPDATE account

SET balance = balance + 100

WHERE id = 1;

-- Check the updated row

SELECT ctid, xmin, xmax, *

FROM account

WHERE id = 1;

This might return:

1

2

3

ctid | xmin | xmax | id | balance

--------+------+------+----+---------

(0,4) | 757 | 0 | 1 | $600.00

Notice several important changes:

- The row now has a new

ctidvalue (0,4) - The

xminvalue is now 757 (our current transaction ID) - This is a new version of the row

What happened to the old version? It’s still in the database, but we can’t see it directly from this transaction. If we open a new database session while our transaction is still in progress, we can see the original value:

1

2

3

4

-- In a new database session

SELECT ctid, xmin, xmax, *

FROM account

WHERE id = 1;

This would show:

1

2

3

ctid | xmin | xmax | id | balance

--------+------+------+----+---------

(0,1) | 755 | 757 | 1 | $500.00

Notice that the xmax value of the original row is now 757 - the ID of our transaction that’s updating it. This marks the row as deleted by our transaction, but it’s still visible to other transactions that started before ours.

When we commit our transaction:

1

COMMIT;

Now all new transactions will see only the new version of the row:

1

2

3

SELECT ctid, xmin, xmax, *

FROM account

WHERE id = 1;

1

2

3

ctid | xmin | xmax | id | balance

--------+------+------+----+---------

(0,4) | 757 | 0 | 1 | $600.00

Examining PostgreSQL Page Structure

The examples above show what’s visible through SQL queries, but what’s actually stored inside the PostgreSQL heap pages? To see this, we can use the pageinspect extension:

1

CREATE EXTENSION pageinspect;

Now we can examine the raw contents of a page:

1

SELECT * FROM heap_page_items(get_raw_page('account', 0));

This might give us:

1

2

3

4

5

6

lp | lp_off | lp_flags | lp_len | t_xmin | t_xmax | t_field3 | t_ctid | t_infomask2 | t_infomask | t_hoff | t_bits | t_oid | t_data

----+--------+----------+--------+--------+--------+----------+--------+-------------+------------+--------+--------+-------+--------------------------

1 | 8152 | 1 | 32 | 755 | 757 | 0 | (0,4) | 2 | 2306 | 24 | | | \x0100000000000000c42c

2 | 8120 | 1 | 32 | 756 | 0 | 0 | (0,2) | 2 | 2304 | 24 | | | \x0200000000000000d22c

3 | 8088 | 1 | 32 | 756 | 0 | 0 | (0,3) | 2 | 2304 | 24 | | | \x0300000000000000e02c

4 | 8056 | 1 | 32 | 757 | 0 | 0 | (0,4) | 2 | 2304 | 24 | | | \x0100000000000000c832

We can see four row versions here:

- The original account with ID 1 (with

t_xmin755 andt_xmax757) - Accounts with IDs 2 and 3 (both with

t_xmin756) - The updated account with ID 1 (with

t_xmin757)

For a more intuitive view, we can create a stored procedure that formats this information more clearly:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

CREATE OR REPLACE FUNCTION heap_page(rel text, page integer)

RETURNS TABLE(

line_id integer,

ctid tid,

state text,

xmin text,

xmin_age integer,

xmax text,

xmax_age integer,

hhu boolean,

hot boolean,

t_ctid tid

) AS $$

DECLARE

page_data bytea;

page_item record;

page_header record;

tuple record;

infomask integer;

infomask2 integer;

current_xid txid;

BEGIN

-- Get the current transaction ID

current_xid := txid_current();

-- Get page data

page_data := get_raw_page(rel, page);

-- Get page header

page_header := PageHeaderData(page_data);

-- Loop through all items in the page

FOR page_item IN SELECT * FROM heap_page_items(page_data) LOOP

-- Extract information about the tuple

infomask := page_item.t_infomask;

infomask2 := page_item.t_infomask2;

-- Extract tuple header data

tuple := (

page_item.t_xmin,

page_item.t_xmax,

page_item.t_ctid,

infomask,

infomask2

);

-- Return the formatted information

line_id := page_item.lp;

ctid := rel || '(' || page || ',' || page_item.lp || ')';

-- Determine tuple state

state := CASE

WHEN (infomask & 128) > 0 THEN 'redirect: ' || page_item.t_ctid

WHEN (infomask & 16) > 0 THEN 'dead'

ELSE 'normal'

END;

-- Format xmin with status

xmin := page_item.t_xmin::text;

IF page_item.t_xmin > 0 THEN

IF (infomask & 256) > 0 THEN

xmin := xmin || ' (c)'; -- committed

ELSIF (infomask & 512) > 0 THEN

xmin := xmin || ' (a)'; -- aborted

ELSE

xmin := xmin || ' (i)'; -- in progress

END IF;

xmin_age := current_xid - page_item.t_xmin;

ELSE

xmin_age := NULL;

END IF;

-- Format xmax with status

xmax := page_item.t_xmax::text;

IF page_item.t_xmax > 0 THEN

IF (infomask & 1024) > 0 THEN

xmax := xmax || ' (c)'; -- committed

ELSIF (infomask & 2048) > 0 THEN

xmax := xmax || ' (a)'; -- aborted

ELSE

xmax := xmax || ' (i)'; -- in progress

END IF;

xmax_age := current_xid - page_item.t_xmax;

ELSE

xmax_age := NULL;

END IF;

-- Set special flags

hhu := (infomask & 16384) > 0; -- HOT updated

hot := (infomask2 & 8192) > 0; -- heap-only tuple

t_ctid := page_item.t_ctid;

RETURN NEXT;

END LOOP;

END;

$$ LANGUAGE plpgsql;

Now we can run:

1

SELECT * FROM heap_page('account', 0);

This might return:

1

2

3

4

5

6

line_id | ctid | state | xmin | xmin_age | xmax | xmax_age | hhu | hot | t_ctid

---------+-------------------+---------+-------------+----------+------------+----------+------+------+----------

1 | account(0,1) | normal | 755 (c) | 8 | 757 (c) | 6 | true | false| (0,4)

2 | account(0,2) | normal | 756 (c) | 7 | 0 (a) | | false| false| (0,2)

3 | account(0,3) | normal | 756 (c) | 7 | 0 (a) | | false| false| (0,3)

4 | account(0,4) | normal | 757 (c) | 6 | 0 (a) | | false| false| (0,4)

Here we can see several important details:

- The

(c)next to xmin values indicates that these transactions are committed. - The original row (line_id 1) has

hhuset to true, indicating it’s been HOT updated (Heap-Only Tuple). - The

t_ctidpoints to the newer version of the row.

The Accumulation Problem and Garbage Collection

Let’s update all accounts to see what happens to our page:

1

2

3

UPDATE account SET balance = balance + 100;

SELECT * FROM heap_page('account', 0);

This might show:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

line_id | ctid | state | xmin | xmin_age | xmax | xmax_age | hhu | hot | t_ctid

---------+-------------------+---------+-------------+----------+------------+----------+------+------+----------

1 | account(0,1) | normal | 755 (c) | 10 | 757 (c) | 8 | true | false| (0,4)

2 | account(0,2) | normal | 756 (c) | 9 | 758 (c) | 7 | true | false| (0,5)

3 | account(0,3) | normal | 756 (c) | 9 | 758 (c) | 7 | true | false| (0,6)

4 | account(0,4) | normal | 757 (c) | 8 | 758 (c) | 7 | true | false| (0,7)

5 | account(0,5) | normal | 758 (c) | 7 | 0 (a) | | false| false| (0,5)

6 | account(0,6) | normal | 758 (c) | 7 | 0 (a) | | false| false| (0,6)

7 | account(0,7) | normal | 758 (c) | 7 | 0 (a) | | false| false| (0,7)

Now we have seven row versions for just three accounts. Let’s update them again:

1

2

3

UPDATE account SET balance = balance + 100;

SELECT * FROM heap_page('account', 0);

The number of row versions continues to grow! This raises a critical question: How long does PostgreSQL keep these old row versions?

The answer is that PostgreSQL needs to keep old row versions until they’re no longer visible to any active transaction. But it can’t keep them forever, or the database would run out of space. This is where VACUUM comes in.

VACUUM: PostgreSQL’s Garbage Collector

PostgreSQL uses a process called VACUUM to clean up old, no-longer-needed row versions. VACUUM can run in two modes:

- Standard VACUUM: Marks space as reusable but doesn’t return it to the operating system.

- VACUUM FULL: Rewrites the entire table to remove dead rows and returns space to the operating system.

Let’s see VACUUM in action:

1

2

3

VACUUM account;

SELECT * FROM heap_page('account', 0);

After running VACUUM, we should see that only the latest versions of our rows remain visible:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

line_id | ctid | state | xmin | xmin_age | xmax | xmax_age | hhu | hot | t_ctid

---------+-------------------+---------+-------------+----------+------------+----------+------+------+----------

5 | account(0,5) | normal | 758 (c) | 7 | 759 (c) | 3 | true | false| (0,8)

6 | account(0,6) | normal | 758 (c) | 7 | 759 (c) | 3 | true | false| (0,9)

7 | account(0,7) | normal | 758 (c) | 7 | 759 (c) | 3 | true | false| (0,10)

8 | account(0,8) | normal | 759 (c) | 3 | 0 (a) | | false| false| (0,8)

9 | account(0,9) | normal | 759 (c) | 3 | 0 (a) | | false| false| (0,9)

10 | account(0,10) | normal | 759 (c) | 3 | 0 (a) | | false| false| (0,10)

The old row versions are still physically there, but their space has been marked as reusable for future row insertions. Let’s update one row to see this reuse:

1

2

3

UPDATE account SET balance = 1000 WHERE id = 1;

SELECT * FROM heap_page('account', 0);

We might see:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

line_id | ctid | state | xmin | xmin_age | xmax | xmax_age | hhu | hot | t_ctid

---------+-------------------+---------+-------------+----------+------------+----------+------+------+----------

1 | account(0,1) | normal | 760 (c) | 1 | 0 (a) | | false| false| (0,1)

5 | account(0,5) | normal | 758 (c) | 7 | 759 (c) | 3 | true | false| (0,8)

6 | account(0,6) | normal | 758 (c) | 7 | 759 (c) | 3 | true | false| (0,9)

7 | account(0,7) | normal | 758 (c) | 7 | 759 (c) | 3 | true | false| (0,10)

8 | account(0,8) | normal | 759 (c) | 3 | 760 (c) | 1 | true | false| (0,1)

9 | account(0,9) | normal | 759 (c) | 3 | 0 (a) | | false| false| (0,9)

10 | account(0,10) | normal | 759 (c) | 3 | 0 (a) | | false| false| (0,10)

Notice that PostgreSQL reused line_id 1 for the new row version.

For more thorough cleanup, we can use VACUUM FULL:

1

2

3

VACUUM FULL account;

SELECT * FROM heap_page('account', 0);

This would rewrite the table completely and might give us:

1

2

3

4

5

line_id | ctid | state | xmin | xmin_age | xmax | xmax_age | hhu | hot | t_ctid

---------+-------------------+---------+-------------+----------+------------+----------+------+------+----------

1 | account(0,1) | normal | 761 (c) | 0 | 0 (a) | | false| false| (0,1)

2 | account(0,2) | normal | 761 (c) | 0 | 0 (a) | | false| false| (0,2)

3 | account(0,3) | normal | 761 (c) | 0 | 0 (a) | | false| false| (0,3)

Now we only have the three active rows, and their transaction IDs have been updated to the VACUUM FULL transaction.

How Transaction Visibility Works

When a transaction starts in PostgreSQL, it takes a snapshot of the database state. This snapshot determines which row versions the transaction can see. The visibility rules are:

- A row version is visible if its

xminis committed and earlier than the transaction’s snapshot ID, AND:- Its

xmaxis 0 (not deleted), OR - Its

xmaxis aborted (the deleting transaction was rolled back), OR - Its

xmaxis greater than the transaction’s snapshot ID (deleted after the snapshot was taken)

- Its

- A row version is invisible if:

- Its

xminis aborted (the inserting transaction was rolled back), OR - Its

xminis greater than the transaction’s snapshot ID (inserted after the snapshot was taken), OR - Its

xmaxis committed and less than or equal to the transaction’s snapshot ID (deleted before or at the time the snapshot was taken)

- Its

These rules ensure that each transaction sees a consistent snapshot of the database, regardless of concurrent modifications.

Autovacuum: Automated Garbage Collection

While we’ve been running VACUUM manually in our examples, PostgreSQL normally relies on an automatic process called AutoVacuum. AutoVacuum runs in the background and periodically cleans up dead row versions.

The AutoVacuum process:

- Monitors tables for dead row versions

- Runs when certain thresholds are met (configurable)

- Performs standard VACUUM operations to reclaim space

- Updates statistics for the query planner

Key configuration parameters for AutoVacuum include:

autovacuum_vacuum_threshold: Minimum number of row updates before vacuumautovacuum_analyze_threshold: Minimum number of row changes before analyzeautovacuum_vacuum_scale_factor: Fraction of table size to add to thresholdautovacuum_naptime: Time between autovacuum runs

These can be configured at the server or table level for optimal performance.

The Impact of MVCC on Performance

MVCC offers significant advantages for concurrent database access, but it also has implications for performance:

Advantages:

- Concurrency: Readers don’t block writers, and writers don’t block readers

- Consistency: Each transaction sees a coherent snapshot

- Isolation: Transactions are isolated from each other’s changes

Challenges:

- Bloat: Tables and indexes can grow larger due to old row versions

- Vacuum overhead: The cleanup process consumes system resources

- Transaction ID Wraparound: PostgreSQL uses 32-bit transaction IDs, which can wrap around after approximately 4 billion transactions. PostgreSQL prevents this problem by freezing old transaction IDs, but inadequate vacuuming can lead to database shutdown.

To address these challenges effectively:

- Configure AutoVacuum appropriately for your workload

- Monitor table and index bloat regularly

- Schedule maintenance windows for VACUUM FULL on critical tables

- Consider partitioning large tables to make vacuuming more efficient

Low-Level Implementation: Exploring the Assembly Code

To truly understand how PostgreSQL implements MVCC at the lowest level, we can examine the compiled code that handles transaction visibility. This requires compiling PostgreSQL with debugging symbols and using tools like gdb and objdump.

First, let’s compile PostgreSQL with debugging information:

1

2

3

4

git clone https://github.com/postgres/postgres.git

cd postgres

./configure --enable-debug

make

Now, let’s use objdump to examine the assembly code for the HeapTupleSatisfiesMVCC function, which is responsible for determining whether a tuple (row version) is visible to a transaction:

1

objdump -S --disassemble=HeapTupleSatisfiesMVCC src/backend/access/heap/heapam.o

The resulting assembly code is complex, but we can identify key sections:

Transaction Status Check: The function checks the status of the

xminandxmaxtransactions using theTransactionIdIsCurrentTransactionIdandTransactionIdIsInProgressfunctions.Flag Examination: The code examines the tuple header flags to determine if the inserting or deleting transactions are committed or aborted.

Snapshot Comparison: The function compares the transaction IDs with the snapshot taken by the current transaction.

Here’s a simplified interpretation of what the assembly code does:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

HeapTupleSatisfiesMVCC:

# Check if the inserting transaction is still running

if xmin is current transaction:

# Inserting transaction is current transaction

if current transaction mode is READ COMMITTED:

return visible

else:

return not visible (except for special cases)

# Check if the inserting transaction has committed

if xmin is not committed:

# Inserting transaction aborted or still running

return not visible

# Check if the inserting transaction committed before our snapshot

if xmin is not in snapshot:

# Inserting transaction committed after our snapshot

return not visible

# Check if the deleting transaction exists and has committed

if xmax is zero:

# No deleting transaction

return visible

if xmax is current transaction:

# Current transaction is trying to delete this tuple

if current transaction mode is READ COMMITTED:

return not visible

else:

return visible

# Check if the deleting transaction has committed

if xmax is not committed:

# Deleting transaction aborted or still running

return visible

# Check if the deleting transaction committed before our snapshot

if xmax is in snapshot:

# Deleting transaction committed before our snapshot

return not visible

# Deleting transaction committed after our snapshot

return visible

When analyzing the assembly code, we can observe:

- Multiple conditional jumps that implement the visibility rules

- Function calls to check transaction status in the shared transaction status array

- Bit manipulation operations to check tuple header flags

- Memory access patterns designed for efficiency

This low-level implementation is carefully optimized for performance, as this function is called frequently during database operations.

HOT Updates: An Optimization for MVCC

One optimization PostgreSQL uses to improve MVCC performance is Heap-Only Tuples (HOT). When a row is updated and all indexed columns remain unchanged, PostgreSQL can avoid updating indexes by creating a “heap-only” tuple.

The HOT mechanism works as follows:

- When a row is updated, PostgreSQL checks if any indexed columns changed

- If no indexed columns changed, it sets the HOT flag on the new tuple

- The old tuple’s

t_ctidpoints to the new tuple - The index still points to the old tuple

- When accessing via the index, PostgreSQL follows the chain of

t_ctidpointers to find the latest version

This optimization reduces index bloat and improves performance for frequently updated tables, as it avoids expensive index updates.

In our earlier examples, when we used the heap_page function, we saw the hot flag on some tuples. These were HOT updates.

Advanced MVCC Features

PostgreSQL’s MVCC implementation includes several advanced features that go beyond the basic mechanism:

Tuple Freezing

To prevent transaction ID wraparound, PostgreSQL “freezes” old tuples by setting their xmin to a special “frozen” value (2). This indicates that the tuple is visible to all current and future transactions.

Freezing happens during VACUUM operations when tuples are older than vacuum_freeze_min_age transactions.

Commit Timestamp Tracking

Recent PostgreSQL versions can track the exact timestamp when a transaction committed. This enables temporal queries like “as of” queries that show the database state at a specific point in time.

To enable this feature:

1

ALTER SYSTEM SET track_commit_timestamp = on;

Visibility Map

PostgreSQL maintains a visibility map for each table, which tracks which pages contain only tuples that are visible to all transactions. This optimization helps VACUUM skip pages that don’t need cleaning.

MVCC in Action: Practical Examples

Let’s explore some practical examples of how MVCC affects database operations:

Example 1: Lost Update Prevention

In systems without proper concurrency control, the “lost update” problem can occur. MVCC helps prevent this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

-- Session 1

BEGIN;

SELECT balance FROM account WHERE id = 1; -- Returns $600

-- Calculate new balance: $600 + $100 = $700

-- Session 2

BEGIN;

SELECT balance FROM account WHERE id = 1; -- Returns $600

UPDATE account SET balance = balance + 200 WHERE id = 1;

COMMIT;

-- Session 1 (continued)

UPDATE account SET balance = 700 WHERE id = 1; -- Uses WHERE clause with value

COMMIT;

In a system without proper concurrency control, Session 1’s update would overwrite Session 2’s update, losing the +$200 change. With PostgreSQL’s MVCC, Session 1’s UPDATE would fail with a serialization error (in SERIALIZABLE isolation) or would update the row version created by Session 2 (in READ COMMITTED isolation).

Example 2: Consistent Reporting

MVCC is particularly valuable for reporting queries that need a consistent view of the database:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

-- Start a long-running report in one session

BEGIN;

SELECT txid_current(); -- Remember this transaction ID

-- Run analytical queries

SELECT category, SUM(amount) FROM transactions GROUP BY category;

-- More complex queries...

-- Meanwhile, in another session

UPDATE transactions SET amount = amount * 1.1 WHERE category = 'Retail';

INSERT INTO transactions (id, category, amount) VALUES (1001, 'Grocery', 100);

COMMIT;

-- Back in the reporting session

-- This query will still see the original data, unaffected by the updates

SELECT category, SUM(amount) FROM transactions GROUP BY category;

COMMIT;

The reporting transaction maintains a consistent view throughout its execution, regardless of concurrent modifications.

Best Practices for Working with MVCC

To make the most of PostgreSQL’s MVCC system:

- Keep transactions short: Long-running transactions prevent VACUUM from cleaning up old row versions

- Monitor and manage bloat: Regularly check for table and index bloat

- Configure AutoVacuum properly: Adjust AutoVacuum settings based on your workload

- Use appropriate isolation levels: Choose between READ COMMITTED, REPEATABLE READ, and SERIALIZABLE based on your application needs

- Consider the impact of indexes: Each index adds overhead for UPDATE and DELETE operations

- Partition large tables: Partitioning makes vacuum operations more efficient

- Use advisory locks for operations that need to be truly sequential: When you need absolute coordination, consider advisory locks

Conclusion

PostgreSQL’s MVCC implementation provides an elegant solution to the concurrent access problem that databases face. By maintaining multiple versions of rows and using sophisticated visibility rules, PostgreSQL enables high concurrency while maintaining data consistency.

Understanding the inner workings of MVCC—how PostgreSQL tracks row versions, determines visibility, and performs garbage collection—can help database administrators and developers optimize their applications and troubleshoot performance issues.

The hidden columns (xmin, xmax, and ctid), the VACUUM process, and other related mechanisms form a comprehensive system that makes PostgreSQL one of the most powerful and flexible database systems available.

Further Reading

For those interested in diving deeper into PostgreSQL’s MVCC implementation, several excellent resources are available: