Microsoft Azure Front Door Part 1: Architecture and Core Concepts

Part 1 of an in-depth technical series exploring Microsoft Azure Front Door architecture, evolution from classic to Standard/Premium tiers, control plane separation, and foundational concepts for global application delivery.

Introduction to Azure Front Door

Microsoft Azure Front Door represents a sophisticated global application delivery network that operates at the edge of Microsoft’s extensive private global network infrastructure. As a Layer 7 HTTP/HTTPS load balancer with integrated content delivery network capabilities, Azure Front Door provides dynamic site acceleration, global load balancing, SSL offloading, and comprehensive security features through Web Application Firewall and DDoS protection mechanisms.

Historical Evolution and Service Maturity

Azure Front Door first achieved general availability in March 2019, emerging from Microsoft’s need to solve complex global application delivery challenges at hyperscale. The service evolved from internal Microsoft infrastructure originally designed to handle traffic for high-volume services like Office 365, Xbox Live, and Azure Portal. This internal heritage provided Azure Front Door with battle-tested capabilities before becoming available to external customers.

The classic Azure Front Door architecture operated as a unified service tier, but Microsoft recognized the diverse requirements across different customer segments and workload types. In response, Microsoft introduced the Standard and Premium tiers, representing a fundamental architectural refinement rather than simple feature packaging. This evolution reflects deeper understanding of application delivery requirements across different security postures, compliance needs, and performance profiles.

Standard Tier Capabilities:

The Standard tier focuses on core global application delivery functions. It provides dynamic and static content acceleration through intelligent caching at Microsoft’s edge locations, global HTTP/HTTPS load balancing with automatic failover, SSL/TLS termination with certificate management, basic Web Application Firewall policies, and comprehensive traffic analytics. The Standard tier represents the baseline for organizations requiring global presence without advanced security or private connectivity requirements.

Premium Tier Advanced Features:

The Premium tier extends Standard capabilities with enterprise-grade security and networking features. It adds advanced Web Application Firewall policies with Microsoft Threat Intelligence integration, bot protection using machine learning models trained on billions of requests, Azure Private Link integration enabling secure connectivity to origin services without public internet exposure, enhanced analytics with near real-time metrics and detailed security reports, and integration with Azure Sentinel for security information and event management.

The critical distinction between tiers manifests at the architectural level. Premium tier customers gain access to Microsoft’s threat intelligence feeds, enabling proactive protection against emerging attack patterns. The Private Link integration fundamentally changes the security model by eliminating public internet exposure for backend services, a requirement for organizations with stringent compliance mandates.

Classic to Standard/Premium Migration:

Microsoft announced that Azure Front Door classic will retire on March 31, 2027, requiring all customers to migrate to Standard or Premium tiers. This retirement reflects architectural improvements in the newer service model, including improved control plane stability, enhanced configuration management, and better isolation between tenant configurations. The migration path involves API version changes and configuration model updates, but Microsoft provides automated migration tools and comprehensive documentation to facilitate the transition.

Positioning Within Azure Networking Ecosystem

Azure Front Door occupies a specific niche within Azure’s comprehensive networking portfolio, complementing rather than competing with other services. Understanding these relationships clarifies appropriate use cases and architectural patterns.

Azure Content Delivery Network:

Azure CDN focuses primarily on caching static content at edge locations worldwide. While CDN provides basic request routing and SSL offloading, it lacks the sophisticated application-layer routing, health probing, and failover capabilities of Azure Front Door. Organizations typically use Azure CDN for media streaming, software distribution, and static asset delivery, while Azure Front Door handles dynamic application traffic requiring intelligent routing decisions.

The technical distinction lies in the routing intelligence. Azure CDN uses simple origin failover based on HTTP status codes, while Azure Front Door implements comprehensive health probing with customizable thresholds, backend weighting for gradual traffic shifting, and session affinity mechanisms. Additionally, Azure Front Door’s Web Application Firewall operates at the edge before requests reach origin servers, providing security that Azure CDN cannot match.

Azure Application Gateway:

Application Gateway operates as a regional Layer 7 load balancer deployed within a specific Azure region. It provides features like path-based routing, SSL termination, Web Application Firewall, and cookie-based session affinity. However, Application Gateway fundamentally differs from Azure Front Door in scope and deployment model.

Application Gateway requires deployment within an Azure Virtual Network, consuming subnet IP addresses and operating as infrastructure under customer management. This provides fine-grained control but requires customers to manage high availability, scaling, and multi-region deployments. In contrast, Azure Front Door operates as a fully managed global service, with Microsoft handling infrastructure, updates, and global distribution.

Architectural patterns commonly combine both services. Azure Front Door serves as the global entry point, routing traffic to regional Application Gateway instances that provide additional Layer 7 processing within Virtual Networks. This pattern enables global load balancing with regional security policy enforcement and internal network integration.

Azure Traffic Manager:

Traffic Manager provides DNS-based global load balancing, returning different IP addresses based on routing policies like performance, priority, geographic, or weighted distribution. Traffic Manager operates at the DNS layer rather than the HTTP layer, providing a fundamentally different approach to traffic distribution.

DNS-based load balancing introduces challenges that HTTP-layer routing avoids. DNS caching by recursive resolvers means traffic distribution changes propagate slowly, typically requiring TTL expiration before taking effect. Client DNS resolvers may ignore TTL values or cache responses beyond specified times, reducing routing precision. Additionally, DNS-based geographic routing relies on resolver location rather than client location, which may differ significantly.

Azure Front Door provides instant traffic routing changes without DNS propagation delays. Health probe failures trigger immediate backend removal from rotation, and configuration changes apply within 5 to 10 minutes globally. This responsiveness makes Azure Front Door superior for dynamic traffic management scenarios like blue-green deployments, canary releases, and instant failover.

Architecturally, Traffic Manager and Azure Front Door can work together. Traffic Manager can route between Azure Front Door and alternative CDN providers or direct origin access, providing multi-CDN strategies for maximum resilience. However, for most use cases, Azure Front Door’s HTTP-layer routing provides sufficient flexibility without additional DNS complexity.

Role as Global Entry Point

Azure Front Door functions as the primary global entry point for web applications, sitting at the boundary between end users and backend services. This positioning creates specific responsibilities and capabilities that define the service’s value proposition.

Anycast IP Addressing and Global Distribution:

Azure Front Door uses IP Anycast to advertise the same IP address from multiple Points of Presence worldwide. When clients resolve Azure Front Door domain names, they receive Anycast IP addresses that route to the nearest PoP based on Border Gateway Protocol routing metrics. This approach minimizes network latency by ensuring clients connect to geographically proximate edge locations.

The Anycast implementation requires sophisticated coordination between Azure Front Door’s network operations and Microsoft’s global backbone network. Microsoft announces Azure Front Door IP prefixes from multiple locations via BGP, with routing policies configured to prefer shorter AS paths and lower latencies. Internet service providers and peering partners select optimal paths based on these announcements, directing client traffic to the closest Azure Front Door PoP.

Edge Processing and Origin Offload:

Processing requests at the edge provides multiple benefits beyond latency reduction. SSL/TLS termination at edge locations offloads computationally expensive cryptographic operations from origin servers, reducing CPU consumption and enabling greater origin capacity. HTTP/2 and HTTP/3 protocol support at the edge allows modern protocol benefits even when origins support only HTTP/1.1, improving performance without origin modifications.

Caching at edge locations reduces origin requests for cacheable content, significantly decreasing origin load and improving response times. Azure Front Door implements sophisticated caching strategies based on HTTP headers, URL patterns, and query strings, with cache purge APIs for immediate invalidation when content updates occur.

Global Load Balancing and Failover:

Azure Front Door’s global load balancing operates continuously, monitoring backend health and adjusting traffic distribution in real time. Health probes originate from multiple edge locations, providing distributed visibility into backend availability and performance. When backends fail health checks, Azure Front Door immediately removes them from rotation, directing traffic to healthy alternatives.

The failover mechanism operates at multiple levels. Within a backend pool, Azure Front Door distributes traffic across healthy backends using configured load balancing algorithms. Across backend pools, priority and weight settings enable primary-secondary patterns or proportional traffic distribution. This multi-level approach supports complex deployment patterns like active-active, active-passive, and gradual traffic shifting for canary releases.

High-Level Architecture Overview

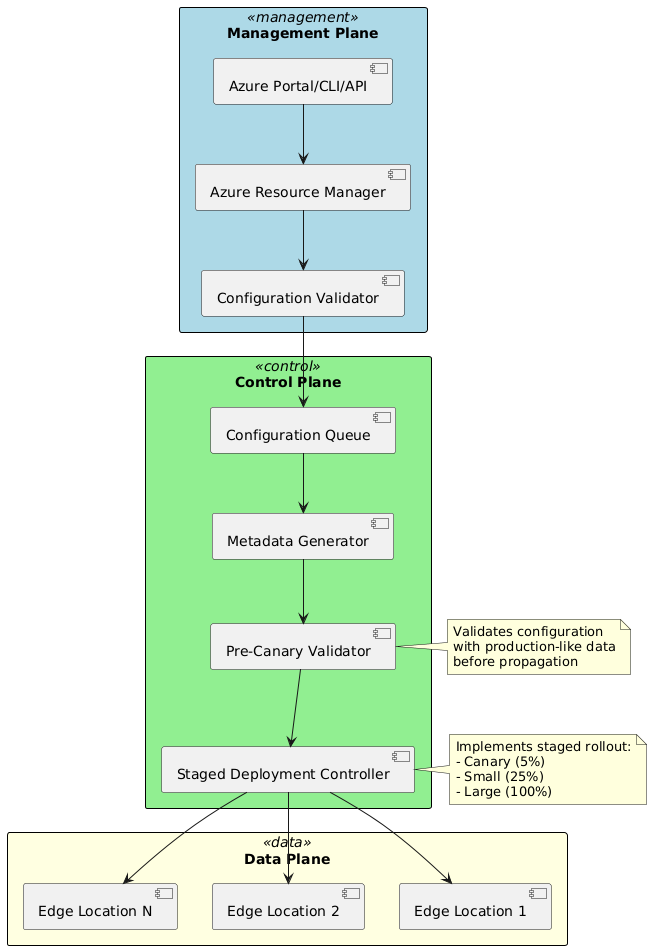

Azure Front Door’s architecture represents a sophisticated distributed system spanning three distinct operational planes: management plane, control plane, and data plane. Understanding these planes and their interactions provides essential context for comprehending the service’s operational characteristics and failure modes.

Control and Data Plane Separation

The separation between control plane and data plane reflects fundamental distributed systems design principles, isolating configuration management from request processing to enhance reliability and scalability.

Management Plane:

The management plane handles customer interactions through Azure Resource Manager, Azure Portal, Azure CLI, PowerShell, and REST APIs. When customers create or modify Azure Front Door profiles, routing rules, backend pools, or WAF policies, these operations flow through the management plane. The management plane validates configurations, enforces access controls using Azure RBAC, and initiates configuration propagation to the control plane.

Management plane operations execute asynchronously, returning operation IDs that customers can poll for completion status. This asynchronous model accommodates the complexity of global configuration distribution, which may require minutes to complete across hundreds of edge locations. The management plane maintains authoritative configuration state in durable storage, providing the source of truth for configuration recovery and auditing.

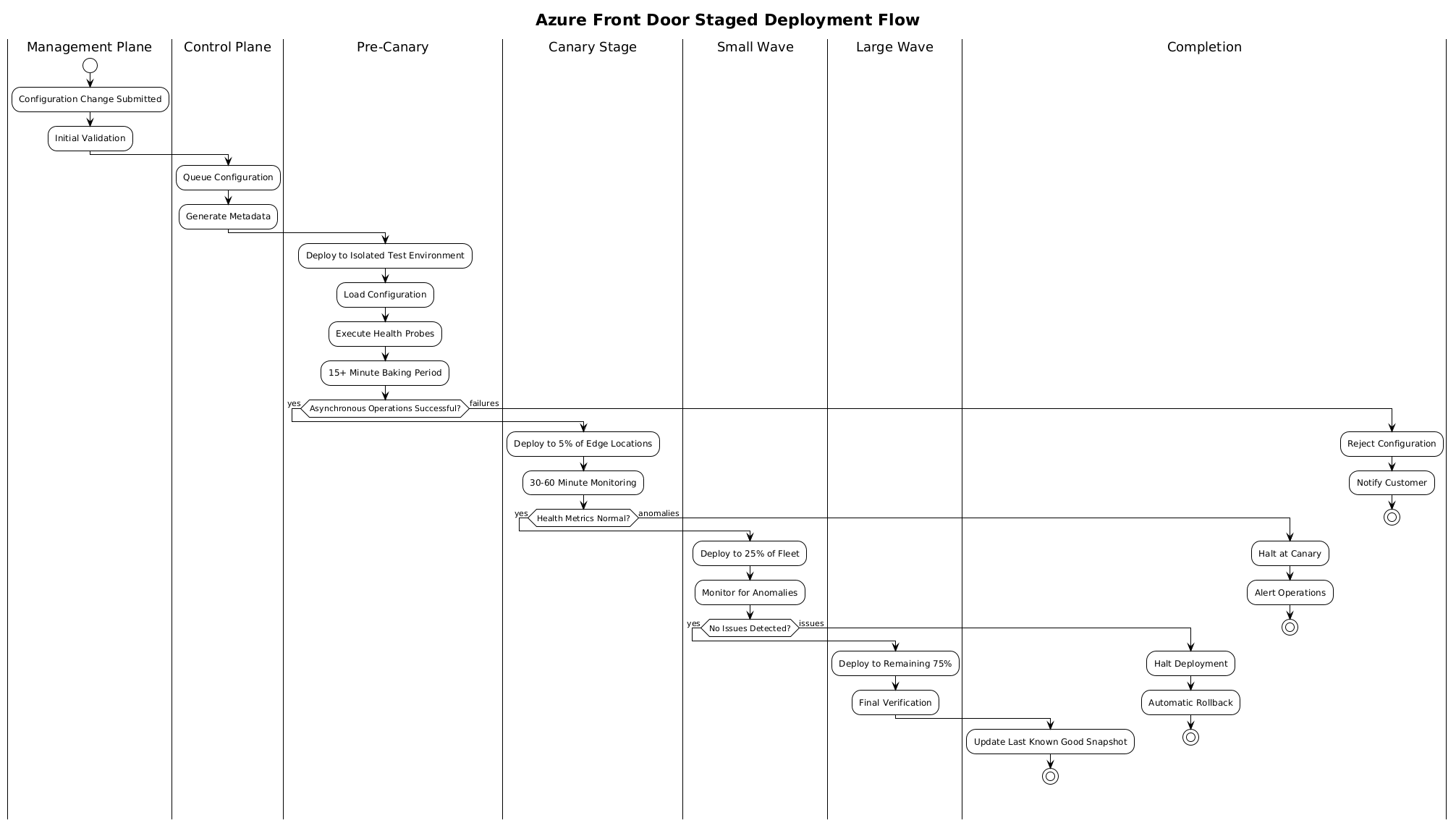

Control Plane:

The control plane receives validated configurations from the management plane and orchestrates their distribution to data plane edge locations. This orchestration involves several critical functions: configuration compilation and optimization, staged deployment with health validation, metadata generation for data plane consumption, and global state synchronization.

The control plane operates as a distributed system across multiple Azure regions, providing resilience against regional failures. Configuration changes propagate through a staged deployment process designed to detect errors before global rollout. The staging strategy includes pre-canary validation where configurations are tested in isolated environments, canary deployments to small subsets of edge locations with extended monitoring periods, gradual rollout to larger populations with continuous health assessment, and automatic halt mechanisms that stop propagation when failures are detected.

The October 2024 Azure Front Door outage demonstrated vulnerabilities in this control plane architecture when configuration incompatibilities manifested asynchronously after passing synchronous validation checks. Microsoft’s response included architectural changes to improve detection of asynchronous failures and extend validation periods to allow background operations to complete before propagation continues.

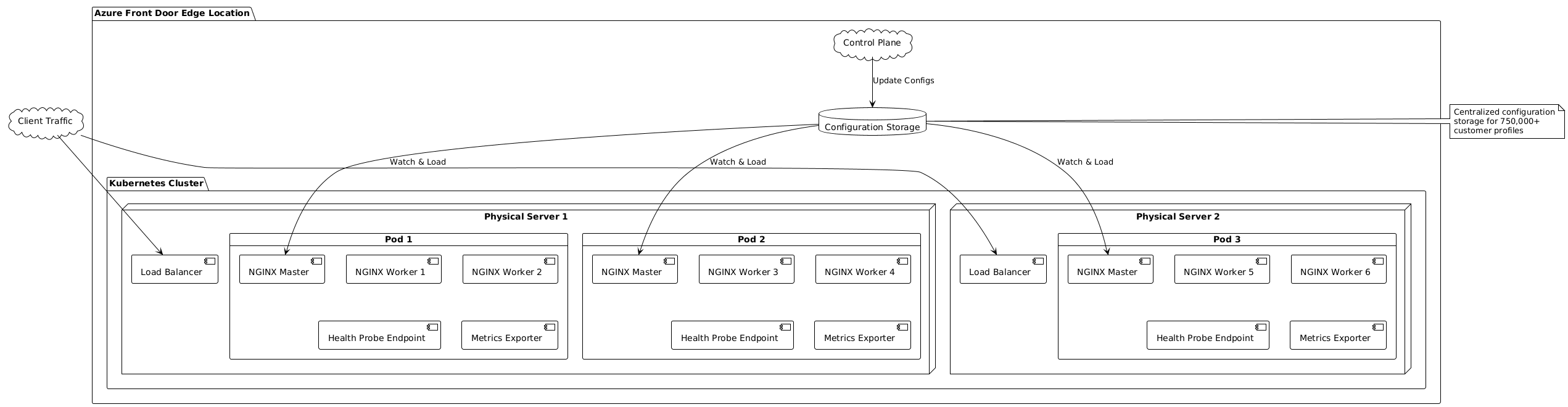

Data Plane:

The data plane comprises edge locations distributed globally, handling actual client request processing. Each edge location runs NGINX-based proxy processes within Kubernetes pods, providing request routing, caching, SSL/TLS termination, and WAF enforcement. The data plane maintains local configuration state received from the control plane, enabling continued operation even when control plane connectivity is disrupted.

Data plane edge locations implement sophisticated request processing pipelines. Incoming requests first undergo protocol processing, extracting HTTP headers, URLs, and other metadata. Routing rule evaluation determines the appropriate backend pool based on URL patterns, headers, or custom conditions. Backend selection within pools uses load balancing algorithms and health probe results to identify optimal targets. Request forwarding to selected backends occurs over Microsoft’s private global network, with automatic retry on transient failures. Response processing applies caching rules, compression, and any configured transformations before delivery to clients.

Frontends, Hosts, and Domain Management

Frontends represent the public-facing endpoints that clients access, involving domain configuration, SSL certificate management, and routing rule association.

Frontend Host Configuration:

When creating an Azure Front Door profile, customers receive a default frontend host with the format profilename.azurefd.net. This default frontend uses Microsoft-managed SSL certificates with automated renewal, providing immediate HTTPS capability without certificate management overhead. However, production applications typically require custom domains matching organizational branding and DNS structures.

Custom domain configuration involves several steps: domain ownership verification through DNS TXT records, SSL certificate provisioning either through Azure Front Door managed certificates or customer-provided certificates stored in Azure Key Vault, and CNAME record creation pointing the custom domain to the Azure Front Door frontend.

SSL Certificate Management:

Azure Front Door provides two certificate management options with distinct operational characteristics. Azure-managed certificates use Azure’s integration with DigiCert to automatically provision and renew certificates, with wildcard support for subdomain flexibility. This option eliminates certificate management burden but requires DNS control for domain validation.

Customer-managed certificates stored in Azure Key Vault provide greater control and support Extended Validation certificates, organization-validated certificates, and custom certificate authorities. Azure Front Door monitors Key Vault for certificate updates and automatically applies new versions, but customers remain responsible for renewal before expiration. The integration uses Azure managed identities to access Key Vault without embedding credentials in configurations.

Server Name Indication and Multi-Domain Support:

Azure Front Door uses Server Name Indication to support multiple SSL certificates on the same IP address. During TLS handshake, clients include the requested hostname in the ClientHello message, allowing Azure Front Door to select the appropriate certificate. This approach enables hosting multiple domains with different certificates on shared infrastructure.

The SNI implementation requires careful consideration for clients that do not support SNI, primarily older browsers and HTTP clients. Azure Front Door’s Anycast IP addresses do not provide fallback certificate behavior, so non-SNI clients may encounter certificate mismatch errors when accessing custom domains. Organizations supporting legacy clients may need alternative approaches like dedicated IP addresses or HTTP-to-HTTPS redirect with warning pages.

Backend Pools and Origin Configuration

Backend pools represent collections of origin servers that handle application logic and content generation. Proper backend pool configuration critically impacts performance, reliability, and security.

Backend Pool Composition:

Backend pools contain one or more backend endpoints, which can be Azure App Services, Virtual Machines, Azure Kubernetes Service, Azure Functions, or any publicly accessible HTTP/HTTPS endpoint including on-premises servers and other cloud providers. This flexibility enables hybrid and multi-cloud architectures with Azure Front Door providing unified global entry points.

Each backend within a pool has configurable properties: hostname and port specifying connection details, weight controlling traffic distribution proportion, priority enabling primary-secondary patterns, and enabled/disabled state for operational control without configuration removal.

Backend Weight and Priority:

Weight and priority provide complementary traffic distribution mechanisms. Priority creates primary-secondary relationships where backends with priority 1 receive all traffic until failures occur, then priority 2 backends activate. Within the same priority level, weight determines proportional traffic distribution, enabling scenarios like 80/20 splits for canary testing or gradual traffic migration.

The implementation evaluates priority first, selecting only backends with the lowest priority value among healthy backends. Then within that priority level, weight values determine the probability of backend selection for each request. This two-tier approach supports common patterns like active-passive with weighted distribution among active backends, or all backends at the same priority with weights controlling proportional distribution.

Backend Timeout and Keep-Alive:

Azure Front Door maintains connection pools to backends, reusing TCP connections across multiple requests to reduce latency. The backend timeout setting determines how long Azure Front Door waits for backend responses before returning timeout errors to clients. Default timeout is 30 seconds, but applications with long-running operations may require higher values.

Keep-alive behavior reuses connections when possible but respects Connection: close headers from backends. This connection reuse significantly reduces overhead for HTTPS connections, avoiding repeated TLS handshakes. However, backends must correctly handle connection reuse, implementing proper request delimiting and avoiding state corruption across requests.

Routing Rules and Request Forwarding

Routing rules define how Azure Front Door forwards requests from frontends to backend pools, implementing the core routing intelligence that distinguishes Azure Front Door from simpler load balancers.

Pattern Matching and Route Prioritization:

Routing rules use pattern matching against request URLs to determine backend pool selection. Patterns support exact matches, wildcard matches, and path prefixes. When multiple rules match a request, Azure Front Door applies the most specific match based on rule ordering and specificity.

Each routing rule specifies accepted protocols (HTTP, HTTPS, or both), forwarding protocol (HTTP, HTTPS, or match request), and caching behavior. This flexibility supports scenarios like HTTP to HTTPS redirect, protocol upgrade from HTTP/1.1 to HTTP/2, and selective caching based on URL patterns.

URL Rewrite and Redirect:

URL rewrite modifies request paths before forwarding to backends, enabling path translation scenarios. For example, Azure Front Door can accept requests at /api/v2/* and forward to backends at /v2/*, removing the /api prefix. This capability supports API versioning, backend service abstraction, and gradual migration from legacy URL structures.

URL redirect generates HTTP 301, 302, 307, or 308 responses directing clients to different URLs without backend involvement. Common use cases include HTTP to HTTPS redirect for security, domain consolidation redirecting multiple domains to a canonical domain, and URL normalization removing trailing slashes or enforcing lowercase.

Query String Handling:

Azure Front Door provides configurable query string behavior affecting both caching and backend forwarding. Query string inclusion in cache keys determines whether requests with different query parameters generate separate cache entries or share cached responses. This setting critically impacts caching effectiveness and resource consumption.

The “ignore query string” option treats all URLs with the same path as identical, maximizing cache hit rates but potentially serving incorrect content when query parameters affect responses. The “use query string” option includes full query strings in cache keys, ensuring correctness but reducing cache efficiency. The “ignore specified query strings” option provides middle ground, including only specified parameters in cache keys while ignoring tracking or analytics parameters that do not affect content.

Health Probes and Backend Monitoring

Health probes provide the mechanism by which Azure Front Door assesses backend availability and responsiveness, forming the foundation for intelligent traffic routing and automatic failover.

Probe Configuration and Behavior:

Health probes execute periodically from multiple edge locations, sending HTTP or HTTPS requests to configured backend endpoints. Each probe specifies the protocol (HTTP or HTTPS), path to request, interval between probes (default 30 seconds), and probe method (GET or HEAD).

The probe path should return quickly and accurately reflect backend health. Implementing health endpoints that verify backend dependencies like database connectivity, external service availability, and resource capacity provides higher fidelity health signals than simple HTTP 200 responses. However, health endpoints must execute quickly to avoid timeout false positives, typically completing within 5 seconds.

Health Assessment Thresholds:

Azure Front Door evaluates probe responses against configured thresholds to determine backend health state. The sample size setting determines how many recent probe results to consider, while the threshold specifies how many successful probes are required within the sample size to mark a backend healthy.

For example, with sample size 4 and threshold 2, Azure Front Door examines the most recent 4 probe results and requires at least 2 successes to mark the backend healthy. This sliding window approach provides smoothing against transient failures while responding quickly to persistent problems. Conservative settings like sample size 10 with threshold 6 reduce false positives from network blips but slower to detect actual failures. Aggressive settings like sample size 2 with threshold 2 respond quickly but may cause unnecessary failover due to transient issues.

Probe Distribution and Timing:

Health probes originate from multiple Azure Front Door edge locations, providing distributed perspective on backend health. This distribution detects regional network issues, partial backend failures, and anycast routing problems that might affect only certain geographic areas. However, it also generates more backend traffic, which must be considered in capacity planning.

The probe interval applies per edge location rather than globally, meaning backends receive probes from dozens of locations simultaneously. For a 30-second probe interval from 100 edge locations, backends receive approximately 200 probes per minute. This traffic is generally insignificant but may impact rate limiting or billing for backends charged per request.

Web Application Firewall Integration

Web Application Firewall provides security protection at the Azure Front Door edge, inspecting requests before they reach backend services and blocking malicious traffic.

WAF Policy Association:

WAF policies attach to Azure Front Door frontend hosts, applying security rules to all requests for associated domains. The policy association model enables different security postures for different frontends within the same Azure Front Door profile, supporting scenarios like stricter rules for administrative interfaces versus public APIs.

WAF policy evaluation occurs early in the request processing pipeline, before routing rule evaluation or backend selection. Blocked requests return HTTP 403 responses without consuming backend resources or generating backend logs, improving security and reducing attack surface.

Managed Rule Sets:

Azure Front Door WAF provides managed rule sets based on OWASP Core Rule Set, providing protection against common web vulnerabilities like SQL injection, cross-site scripting, remote code execution, and path traversal. Microsoft maintains these rule sets, updating them as new vulnerabilities emerge and attack patterns evolve.

The managed rule sets use parameterized detection logic rather than simple signature matching, reducing false positives while maintaining broad coverage. Rules examine request components including URL path and query string, HTTP headers, POST body for supported content types, and cookies. The multi-component inspection detects attack patterns split across multiple fields to evade simple filters.

Custom Rules and Rate Limiting:

Custom rules supplement managed rule sets with application-specific security logic. Custom rules support matching conditions based on geographic location, IP address ranges, request header values, cookie values, request body content, and query string parameters. Match conditions combine using AND/OR logic to implement complex security policies.

Rate limiting rules control request volume from individual IP addresses or geographic regions, mitigating application-layer DDoS attacks and preventing abuse. Rate limits specify maximum requests per minute, with action taken when thresholds exceeded. The challenge mechanism returns CAPTCHA or JavaScript challenge responses, requiring human or browser interaction before allowing requests to proceed.

Core Workings and Full Operational Flow

Understanding the end-to-end request processing flow through Azure Front Door reveals the service’s operational characteristics, performance behaviors, and failure modes. This section traces requests from client initiation through backend response delivery, examining each processing stage in detail.

Client Request Initiation and DNS Resolution

The request processing journey begins before Azure Front Door receives any packets, during DNS resolution when clients translate domain names into IP addresses.

DNS Resolution Process:

When users access an application through Azure Front Door, their browsers or HTTP clients must resolve the domain name to an IP address. For custom domains, DNS CNAME records point to the Azure Front Door frontend hostname (e.g., www.example.com CNAME to example.azurefd.net). Clients perform recursive DNS resolution, querying DNS servers that ultimately reach Azure Front Door’s authoritative DNS servers.

Azure Front Door returns Anycast IP addresses in DNS responses, typically with TTL values of 30 to 60 seconds. These IP addresses are announced from multiple Points of Presence via BGP, causing different geographic locations to advertise the same addresses. Internet routing protocols direct client connections to the topologically nearest PoP, minimizing network latency.

The Anycast approach provides several advantages: clients automatically connect to nearby edge locations without geolocation lookups or complex DNS logic, edge location failures trigger automatic BGP withdrawal, rerouting clients to alternative PoPs, and capacity scales naturally as Microsoft adds new edge locations without DNS changes.

TCP Connection Establishment:

After DNS resolution, clients initiate TCP connections to Azure Front Door Anycast addresses. The TCP three-way handshake completes at the edge location, establishing connection state. For HTTPS requests, TLS handshake follows TCP establishment, negotiating encryption parameters and verifying certificates.

Azure Front Door terminates TCP connections at the edge rather than proxying packets to backends. This connection termination provides several benefits: protocol conversion enabling HTTP/2 or HTTP/3 to clients while using HTTP/1.1 to backends, connection multiplexing where multiple client connections share fewer backend connections, and reduced round-trip latency as TCP handshakes complete at nearby edge locations rather than distant backends.

Ingress Processing at the Edge Location

Once clients establish connections, edge locations perform several processing steps before forwarding requests to backends.

TLS Termination and Certificate Validation:

For HTTPS requests, Azure Front Door terminates TLS at the edge, decrypting requests for inspection and processing. The TLS termination process involves several steps: certificate selection based on SNI hostname, cipher suite negotiation supporting modern protocols like TLS 1.3, session resumption using tickets or IDs for performance, and forward secrecy using ephemeral Diffie-Hellman key exchange.

The certificate presented during TLS handshake matches the requested hostname using SNI. Azure Front Door maintains certificate stores at each edge location, updated automatically when certificates change in the control plane. Certificate private keys remain secured in hardware security modules or secure enclaves, never exposed in plaintext to processing software.

Protocol Processing and HTTP Parsing:

After TLS termination, Azure Front Door parses HTTP protocol messages, extracting request method, URL, headers, and body. The HTTP parsing implements strict compliance with RFC specifications while maintaining compatibility with real-world client behaviors including irregular header formatting.

Azure Front Door supports HTTP/1.1, HTTP/2, and HTTP/3 on client connections. HTTP/2 support includes multiplexing multiple requests over single connections, server push for performance optimization, and header compression using HPACK. HTTP/3 support uses QUIC protocol over UDP, providing faster connection establishment and improved performance over lossy networks. However, HTTP/3 availability depends on client support and Premium tier licensing.

Header Inspection and Manipulation:

Azure Front Door inspects HTTP headers for routing decisions and security checks. Standard headers like Host, User-Agent, and Accept influence processing behavior. Custom headers can trigger specific routing rules or WAF actions. Azure Front Door also adds headers to requests before forwarding to backends: X-Forwarded-For containing client IP addresses, X-Forwarded-Proto indicating client protocol, X-Azure-ClientIP with client IP (Premium tier), and X-Azure-SocketIP with actual TCP connection endpoint.

These added headers enable backends to implement client-aware logic despite connection proxying. For example, backends can make authorization decisions based on client IP addresses or enforce protocol requirements based on X-Forwarded-Proto.

Web Application Firewall Evaluation:

WAF policy evaluation occurs early in processing, immediately after header parsing. Azure Front Door evaluates requests against configured rule sets in order: custom rules first, enabling organization-specific security logic to execute before managed rules, then managed rule sets for OWASP protections, followed by bot protection rules if configured, and finally rate limiting rules.

Each rule type can take different actions: allow permits the request to continue processing, block returns HTTP 403 with customizable response body, log records the event without blocking, and redirect returns HTTP 302 to alternative URL. The first matching rule determines the action, with explicit allow rules useful for creating exceptions to broader block rules.

When WAF blocks requests, Azure Front Door generates detailed logs including matched rule ID, action taken, request characteristics, and client IP address. These logs integrate with Azure Monitor and Azure Sentinel for security analysis and incident response.

Routing Decision-Making and Rule Evaluation

After ingress processing and security checks, Azure Front Door evaluates routing rules to determine the appropriate backend pool for each request.

Routing Rule Pattern Matching:

Azure Front Door evaluates routing rules in priority order, testing each rule’s pattern against the request URL. Pattern matching supports exact matches for specific paths, prefix matches for hierarchical structures, and wildcard matches using asterisk notation.

For example, a routing configuration might include: exact match /api/auth/* routing to authentication backend pool with no caching, prefix match /api/* routing to API backend pool with customizable cache rules, prefix match /static/* routing to CDN backend pool with aggressive caching, and default match /* routing to general application backend pool.

The most specific matching rule applies. If multiple rules match, Azure Front Door uses rule specificity (exact > prefix > wildcard) and configured priority to determine precedence. This prioritization enables fine-grained control, with specific routes overriding more general patterns.

Protocol and Method Filtering:

Routing rules can filter based on HTTP protocol and method. Protocol filtering restricts rules to HTTP, HTTPS, or both, enabling patterns like HTTP redirecting to HTTPS for security while HTTPS routes normally. Method filtering restricts rules to specific HTTP verbs like GET, POST, PUT, or DELETE, supporting different backends for read versus write operations.

This filtering supports security patterns like read-only backends accepting only GET and HEAD requests, write backends requiring POST, PUT, DELETE with authentication, and method-specific rate limiting protecting write operations from abuse.

Query String and Fragment Handling:

Routing rules apply to URL paths before query strings and fragments. Query string parameters do not affect route selection but influence caching behavior as discussed previously. URL fragments (content after # character) never reach the server, as browsers strip them before sending requests, but Azure Front Door documentation clarifies this behavior to avoid confusion.

Applications requiring query string awareness in routing must implement it within backend logic rather than Azure Front Door routing rules. This design reflects HTTP architecture where query strings provide parameters to resources rather than identifying different resources.

Backend Selection and Load Balancing

After determining the backend pool via routing rules, Azure Front Door selects a specific backend within the pool using configured load balancing algorithms and health probe results.

Priority-Based Selection:

Azure Front Door first filters backends by health status, excluding backends that recently failed health probes. Among healthy backends, priority values determine the candidate set. Only backends with the lowest priority value among healthy backends become candidates for selection. This priority mechanism implements active-passive patterns where priority 1 backends handle all traffic until failures occur, then priority 2 backends activate as fallback.

Within the candidate set at the selected priority level, weight values determine selection probability. Backend weights represent relative proportions rather than absolute values. For example, backends with weights 1, 1, and 2 receive 25%, 25%, and 50% of traffic respectively. This proportional distribution enables gradual traffic shifting for canary deployments and A/B testing.

Session Affinity and Cookie-Based Routing:

Azure Front Door supports session affinity via cookie-based routing, ensuring subsequent requests from the same client reach the same backend. When session affinity is enabled, Azure Front Door adds a cookie to responses containing an encoded backend identifier. Subsequent requests including this cookie route to the specified backend, maintaining session state.

The session affinity implementation provides best-effort guarantees rather than hard guarantees. Backend failures or health probe state changes override affinity, rerouting requests to healthy alternatives. This behavior prioritizes availability over strict affinity, accepting potential session loss during failures rather than directing users to unhealthy backends.

Session affinity introduces operational complexities. Backends become stateful, complicating scaling and maintenance operations. Deployments must implement gradual rollout strategies that allow existing sessions to drain before decommissioning backends. Despite complexities, session affinity remains necessary for applications storing session state in backend memory rather than external stores like Redis or databases.

Health Probe-Based Selection:

Health probe results directly influence backend selection. When Azure Front Door detects probe failures exceeding configured thresholds, it marks backends unhealthy and excludes them from selection. The health state persists until subsequent probes succeed, meeting the configured success threshold.

This behavior creates hysteresis, requiring multiple consecutive successes to transition from unhealthy to healthy. The hysteresis prevents flapping where backends rapidly toggle between healthy and unhealthy due to transient issues. However, it also slows recovery, maintaining backends as unhealthy even after issues resolve until enough probe successes accumulate.

Load Balancing Algorithms:

Azure Front Door implements several load balancing algorithms, selectable per backend pool. Latency-based routing (default) monitors backend response times via health probes and routes to backends with lowest observed latency. This algorithm optimizes for performance, automatically adapting to backend performance changes. However, it can cause uneven traffic distribution if backend capacities differ.

Priority-based routing distributes traffic by priority and weight as described above, ignoring latency differences. This algorithm provides predictable traffic distribution matching configured weights, useful for capacity-aware routing where backend sizes differ.

Weighted round-robin was the original algorithm, distributing requests sequentially weighted by backend weight values. However, Azure Front Door now recommends latency-based routing for most use cases due to its dynamic adaptation to backend performance.

Backend Request Forwarding

After selecting a backend, Azure Front Door forwards requests over Microsoft’s private global network, leveraging dedicated fiber connections between edge locations and Azure regions.

Connection Establishment and Pooling:

Azure Front Door maintains connection pools to backends, reusing TCP connections across multiple requests. Connection reuse significantly reduces overhead, avoiding repeated TCP handshakes and TLS negotiations. The connection pooling implementation includes connection limits per backend preventing resource exhaustion, idle timeout closing connections inactive beyond configured duration, and connection health monitoring detecting half-open connections.

When forwarding requests to backends using HTTPS, Azure Front Door establishes TLS connections, presenting client certificates if configured for mutual TLS authentication. Backend certificate validation ensures connections target legitimate backends rather than man-in-the-middle attackers. Azure Front Door validates backend certificates against system trust stores, with options to allow custom certificate authorities or disable validation for testing scenarios (not recommended for production).

Request Transformation:

Azure Front Door modifies requests before forwarding to backends. Header additions include X-Forwarded-* headers documenting client information, protocol modifications converting between HTTP versions, and URL rewrites applying configured transformations. These modifications enable backends to receive normalized requests regardless of client protocol version or routing path.

Configurable options control request transformation behavior. The “preserve host header” setting determines whether Azure Front Door sends the original Host header or replaces it with the backend hostname. Preserving the host header enables backends to serve multiple domains from the same application, while replacing it supports backends requiring specific host values. The “forwarding protocol” setting controls whether Azure Front Door uses HTTP, HTTPS, or matches the client protocol when connecting to backends.

Timeout and Retry Behavior:

Azure Front Door waits for backend responses according to configured timeout values, defaulting to 30 seconds for the first byte. If backends exceed this timeout, Azure Front Door returns HTTP 504 Gateway Timeout to clients. The timeout applies to the entire request-response cycle, not just initial connection establishment, accommodating applications with long processing times.

When backends return errors or fail to respond, Azure Front Door implements retry logic. Retries occur for network errors, connection failures, and certain HTTP status codes like 502, 503, and 504. The retry mechanism selects alternative backends within the same pool, potentially succeeding when the original backend failed. However, retries increase latency and backend load, so Azure Front Door limits retry attempts to prevent amplification during outages.

Protocol Conversion:

Azure Front Door can convert between HTTP protocol versions, accepting HTTP/2 or HTTP/3 from clients while using HTTP/1.1 to backends. This conversion provides benefits without requiring backend modifications. Clients gain HTTP/2 multiplexing and header compression, while backends use simpler HTTP/1.1 implementation.

The protocol conversion includes request framing translating between HTTP/2 streams and HTTP/1.1 requests, header translation including pseudo-headers, and response multiplexing combining multiple HTTP/1.1 backend responses into HTTP/2 streams to clients. This translation occurs transparently, with neither clients nor backends aware of protocol conversion.

Response Processing and Caching

After backends generate responses, Azure Front Door processes them before delivering to clients, applying caching rules, compression, and any configured transformations.

Cache Evaluation and Storage:

Azure Front Door evaluates responses against caching rules to determine cachability. Caching rules consider HTTP headers including Cache-Control, Expires, Pragma, and Vary, as well as configured caching behavior in routing rules. Private responses (Cache-Control: private) are never cached, while public responses with future expiration become cache candidates.

Cached responses are stored in edge location memory and disk, with LRU (Least Recently Used) eviction when capacity limits are reached. Cache keys include URL path, query string (depending on configuration), Accept-Encoding header, and host header. This multi-component key ensures correct responses for varied client capabilities like gzip support while sharing cached content where appropriate.

Cache Hit and Miss Behavior:

When subsequent requests match cached entries, Azure Front Door serves responses directly from edge storage without backend involvement. This cache hit scenario provides optimal performance, with response times limited only by edge location network distance. Cache hits also protect backends from load, enabling applications to scale beyond backend capacity for cacheable content.

Cache misses require backend requests, with responses cached according to rules before delivery to clients. The first client requesting non-cached content experiences full backend latency, while subsequent clients benefit from caching. This pattern means cache effectiveness depends on traffic distribution and content popularity.

Conditional Requests and Revalidation:

Azure Front Door supports conditional requests using If-Modified-Since and If-None-Match headers for cache revalidation. When cached content expires, subsequent requests trigger revalidation with backends. Backends can respond with HTTP 304 Not Modified if content remains unchanged, allowing Azure Front Door to serve cached content without full response transfer.

The conditional request mechanism reduces bandwidth consumption while ensuring content freshness. However, it requires backend round-trips for validation, introducing latency compared to serving cached content directly. Caching strategies must balance freshness requirements against performance, using longer TTLs for rarely-changing content and shorter TTLs or no caching for dynamic content.

Response Compression:

Azure Front Door can compress responses before delivery to clients, reducing bandwidth and improving performance for clients on slower connections. Compression applies to text-based content types like HTML, CSS, JavaScript, JSON, and XML. Binary formats like images and video typically use format-specific compression and are excluded.

Compression occurs transparently based on client capabilities indicated via Accept-Encoding headers. Clients supporting gzip or brotli receive compressed responses, while clients lacking compression support receive uncompressed content. Azure Front Door caches both compressed and uncompressed versions separately, serving appropriate versions per client.

Header Manipulation:

Azure Front Door can add, modify, or remove response headers based on configured rules. Common uses include adding security headers like Strict-Transport-Security, X-Frame-Options, and Content-Security-Policy, removing server headers exposing implementation details, and adding custom headers for client application use.

Header manipulation enables security hardening and compliance without backend modifications. Organizations can centrally enforce security headers across multiple backends, ensuring consistent security posture.

Response Delivery to Client

After processing, Azure Front Door delivers responses to clients over the established connection, completing the request lifecycle.

Protocol Encoding:

Azure Front Door encodes responses according to client protocol. For HTTP/2 clients, responses use HTTP/2 framing with HPACK header compression. For HTTP/1.1 clients, responses use traditional HTTP/1.1 encoding. This encoding occurs transparently, matching client expectations.

Connection Management:

Azure Front Door manages client connections according to HTTP protocol requirements and performance considerations. HTTP/1.1 connections support keep-alive, reusing connections for multiple requests. HTTP/2 connections multiplex many requests over single connections, with stream management handling individual request-response pairs.

Connection closing occurs when clients request it via Connection: close header, idle timeout expires with no activity, or error conditions prevent continued use. The connection management balances resource efficiency against performance, maintaining connections when beneficial while closing them to release resources when appropriate.

Error Response Generation:

When errors occur during processing, Azure Front Door generates appropriate HTTP error responses. Common error scenarios include: HTTP 403 Forbidden when WAF blocks requests, HTTP 502 Bad Gateway when backends return invalid responses, HTTP 503 Service Unavailable when no healthy backends exist, HTTP 504 Gateway Timeout when backends exceed response time limits, and HTTP 429 Too Many Requests when rate limits are exceeded.

Error response bodies can be customized per error code, enabling branded error pages with helpful recovery guidance. Custom error pages improve user experience during incidents, providing consistent messaging and recovery paths rather than generic browser error pages.

Low-Level Networking and Protocol Details

Azure Front Door’s operation spans multiple layers of the OSI networking model, with specific implementations at each layer contributing to its overall capabilities. This section examines the low-level networking mechanisms that enable Azure Front Door’s global reach and performance.

Layer 3: Network Layer Implementation

The network layer provides the foundational routing and addressing that directs client traffic to Azure Front Door edge locations.

IP Anycast Routing Mechanics:

Azure Front Door uses IP Anycast addressing to announce the same IP prefixes from multiple geographic locations. When Azure Front Door acquires IP space for this purpose, it configures BGP routers at each Point of Presence to announce these prefixes to upstream providers and peering partners. The BGP announcements include standard routing metrics like AS path length and Multi-Exit Discriminator values that influence route selection by external networks.

Internet routers receiving these BGP announcements install routes to Azure Front Door prefixes via the announcing location. When multiple Azure Front Door PoPs announce the same prefix, routers select routes based on BGP best path selection algorithms, typically preferring shorter AS paths and lower metrics. This selection naturally directs traffic to topologically nearby PoPs, as shorter paths usually indicate fewer network hops and lower latency.

The Anycast implementation requires careful coordination between Azure Front Door network operations and Microsoft’s global network backbone. Route leaking and prefix hijacking present constant threats, so Azure Front Door implements RPKI (Resource Public Key Infrastructure) validation to cryptographically verify BGP announcements. Anycast withdrawal during maintenance or failures must occur cleanly to avoid directing traffic to non-operational locations.

Microsoft Global Network Architecture:

Once client packets reach Azure Front Door PoPs, they traverse Microsoft’s private global network to reach backend destinations. This network comprises extensive fiber infrastructure connecting Microsoft data centers, PoPs, and peering locations worldwide. The private network provides several advantages over public internet transit: reduced latency through optimized paths, enhanced security avoiding public internet threats, improved reliability with redundant paths, and increased bandwidth with dedicated capacity.

Microsoft’s network implements traffic engineering to optimize path selection dynamically. Software-defined networking controllers monitor link utilization, latency, and failure conditions, adjusting routing protocols to select optimal paths. This dynamic optimization responds to network conditions in near real-time, rerouting traffic around congestion or failures to maintain performance.

Packet-Level Routing:

At the packet level, client traffic to Azure Front Door Anycast addresses follows standard IP routing. Client packets contain source IP addresses identifying clients and destination IP addresses targeting Azure Front Door Anycast addresses. Internet routers forward these packets based on destination addresses, using BGP routing tables to select next-hop routers toward Azure Front Door PoPs.

When packets arrive at Azure Front Door PoPs, edge routers accept them and forward to load balancing infrastructure. The load balancing layer distributes packets to appropriate edge servers hosting NGINX proxy processes. This distribution uses ECMP (Equal-Cost Multi-Path) routing or dedicated load balancer appliances, spreading load across available capacity.

Return traffic from Azure Front Door to clients uses source NAT (Network Address Translation), with PoP routers translating backend IP addresses to Azure Front Door Anycast addresses. This translation ensures response packets appear to originate from the address clients contacted, maintaining connection state and avoiding routing asymmetries.

BGP Border Gateway Protocol Details:

Azure Front Door’s BGP implementation follows standard protocols while incorporating Microsoft-specific optimizations. BGP sessions establish between Azure Front Door routers and upstream provider routers, exchanging routing information. Azure Front Door announces its IP prefixes with carefully configured attributes: AS path including Microsoft’s AS numbers, origin type indicating route source, communities for traffic engineering, and next-hop addresses directing traffic to PoP routers.

BGP path selection on receiving routers follows standard algorithms: prefer highest weight, then highest local preference, then shortest AS path, then lowest origin type, then lowest MED, then prefer eBGP over iBGP, then prefer closest next-hop, then prefer oldest route for stability, and finally use router ID as tiebreaker. Azure Front Door influences this selection through community values and MED settings, shaping traffic patterns to balance load and optimize performance.

IPv4 and IPv6 Dual-Stack Support:

Azure Front Door supports both IPv4 and IPv6, implementing dual-stack operation. Frontend hosts receive both IPv4 and IPv6 Anycast addresses, with DNS returning A records (IPv4) and AAAA records (IPv6). Clients preferring IPv6 connect via IPv6 addresses, while IPv4-only clients use IPv4. This dual-stack support ensures broad compatibility while enabling modern IPv6 benefits.

Backend connectivity may use either protocol depending on backend configuration. Azure Front Door can translate between protocols if necessary, accepting IPv6 client connections while using IPv4 to contact backends, or vice versa. This protocol translation bridges IPv4 and IPv6 networks, enabling gradual migration without forcing immediate backend updates.

Layer 4: Transport Layer Implementation

The transport layer manages connection establishment, multiplexing, and reliable data transfer between clients, Azure Front Door, and backends.

TCP Connection Handling:

Azure Front Door terminates TCP connections from clients at edge locations, establishing separate TCP connections to backends. This connection split provides several benefits: protocol conversion enabling HTTP/2 or HTTP/3 to clients with HTTP/1.1 to backends, connection multiplexing allowing multiple client connections to share backend connections, and reduced client latency as TCP handshakes complete at nearby edges rather than distant backends.

TCP handshake begins when clients send SYN (synchronize) packets to Azure Front Door Anycast addresses. Edge location routers receive these packets and forward to edge servers, which respond with SYN-ACK (synchronize-acknowledge) packets. Clients complete handshakes with ACK (acknowledge) packets, establishing connections. This three-way handshake follows standard TCP protocol, typically completing within one round-trip time to the nearest Azure Front Door PoP.

Azure Front Door implements TCP Fast Open where supported, allowing data transmission in SYN packets to eliminate one round-trip. This optimization reduces connection establishment latency for clients that support TFO, particularly beneficial for short-lived connections or first requests after connection closure.

TCP Window Scaling and Congestion Control:

Azure Front Door implements modern TCP congestion control algorithms to optimize throughput. Window scaling extends TCP’s flow control window beyond the 64KB limit in original TCP specifications, enabling high throughput on high-bandwidth-delay-product networks. Azure Front Door negotiates window scaling during connection establishment, with both client-edge and edge-backend connections using appropriate window sizes.

Congestion control algorithms like CUBIC or BBR manage transmission rates to avoid network congestion while maximizing throughput. These algorithms monitor packet loss and round-trip times, adjusting transmission rates dynamically. Azure Front Door tunes congestion control parameters for typical internet conditions, balancing throughput against fairness and stability.

Connection Multiplexing to Backends:

Azure Front Door maintains connection pools to backends, reusing TCP connections across multiple client requests. When clients make requests, Azure Front Door selects existing backend connections from pools rather than establishing new connections for each request. This connection reuse eliminates TCP handshake and TLS negotiation overhead, significantly improving performance.

The multiplexing implementation includes connection limits per backend to prevent resource exhaustion, eviction policies removing idle connections to free resources, and health monitoring detecting broken connections for removal from pools. Connection pooling effectiveness depends on traffic patterns, with high request rates to the same backends enabling efficient reuse while sparse traffic to many backends limits pooling benefits.

QUIC and HTTP/3 Support:

Azure Front Door Premium tier supports QUIC protocol, which underlies HTTP/3. QUIC runs over UDP rather than TCP, providing several advantages: faster connection establishment combining transport and security handshakes, improved performance on lossy networks through independent stream handling, and connection migration allowing clients to change IP addresses without breaking connections.

QUIC implementation in Azure Front Door follows standard specifications while integrating with existing HTTP/2 processing. Clients supporting HTTP/3 attempt UDP connections to port 443, with fallback to TCP if QUIC is unavailable. Azure Front Door advertises HTTP/3 support via Alt-Svc HTTP headers, enabling clients to upgrade from HTTP/2 to HTTP/3 for subsequent requests.

However, QUIC adoption faces challenges. Many corporate networks block or rate-limit UDP traffic, preventing QUIC connections. Middleboxes like firewalls and NAT devices may not correctly handle QUIC, causing connection failures. Azure Front Door implements robust fallback mechanisms, attempting QUIC but reverting to TCP when problems occur, ensuring connectivity despite network interference.

Load Balancing at Layer 4:

While Azure Front Door primarily operates at Layer 7, it implements Layer 4 load balancing for distributing connections across edge servers within PoPs. The Layer 4 load balancing operates on TCP/UDP five-tuple (source IP, source port, destination IP, destination port, protocol), distributing connections without inspecting application-layer content.

Layer 4 load balancing provides advantages including lower latency with minimal processing overhead, high throughput handling millions of connections per second, and protocol agnostic support for any TCP or UDP application. However, Layer 4 cannot make content-aware decisions, requiring Layer 7 processing for URL-based routing and header manipulation.

Azure Front Door uses Layer 4 for initial connection distribution, then Layer 7 for request processing. This hybrid approach balances performance and flexibility, leveraging Layer 4 efficiency while enabling Layer 7 intelligence.

Connection Draining and Graceful Shutdown:

When Azure Front Door removes backends from service due to health probe failures or configuration changes, it implements connection draining to avoid disrupting active requests. New connections route to alternative backends while existing connections complete processing. Azure Front Door waits for configurable drain periods before forcefully closing connections, balancing user experience against recovery speed.

Connection draining applies to both client-edge and edge-backend connections. When edge servers undergo maintenance, Azure Front Door stops routing new client connections to them while allowing active connections to complete. Similarly, when backends are decommissioned, Azure Front Door completes in-flight requests before closing backend connections.

Layer 7: Application Layer Implementation

The application layer provides Azure Front Door’s most sophisticated capabilities, implementing HTTP/HTTPS processing, content-based routing, and security functions.

HTTP Protocol Processing:

Azure Front Door implements comprehensive HTTP protocol support, parsing HTTP/1.1, HTTP/2, and HTTP/3 requests. The HTTP parser extracts request methods, URLs, headers, and bodies, validating protocol compliance while tolerating common deviations for compatibility. Strict parsing detects and rejects malformed requests that might exploit vulnerabilities, while permissive modes accommodate legacy clients.

Request processing includes URL parsing, separating schemes, hostnames, paths, query strings, and fragments. Query string parsing extracts parameters for routing and caching decisions. Header parsing processes potentially thousands of headers per request, with efficient data structures enabling fast lookups. Special handling applies to multi-value headers like Cookie and Set-Cookie, maintaining correct semantics across header concatenation and splitting.

HTTP/2 Multiplexing:

HTTP/2 multiplexing allows multiple request-response pairs over single TCP connections, improving efficiency and performance. Azure Front Door implements full HTTP/2 support including binary framing, stream multiplexing, header compression with HPACK, server push, and stream prioritization. These features operate transparently, with Azure Front Door managing protocol details while applications see standard HTTP semantics.

Stream multiplexing eliminates head-of-line blocking present in HTTP/1.1, where slow responses delay subsequent requests on the same connection. Each HTTP/2 stream operates independently, allowing fast responses to overtake slow ones. This independence particularly benefits loading web pages with many resources, as browsers can request everything immediately without waiting for sequential responses.

Request and Response Header Manipulation:

Azure Front Door provides sophisticated header manipulation capabilities, adding, modifying, or removing headers based on rules. Request header manipulation occurs before backend forwarding, enabling backends to receive enhanced context. Response header manipulation applies before client delivery, enforcing security policies or hiding implementation details.

Header manipulation uses pattern matching and substitution similar to regular expressions. Rules can reference request context like client IP, matched route, or backend target, enabling dynamic header values. For example, rules can add headers indicating which backend served requests, useful for debugging, or remove headers exposing server software versions, improving security.

Content-Based Routing:

Layer 7 routing in Azure Front Door operates on HTTP semantics rather than just network addresses. Routing decisions consider URL paths, query string parameters, HTTP headers including User-Agent and Accept-Language, HTTP methods (GET vs POST), and custom headers for application-specific routing. This content awareness enables sophisticated traffic management impossible at lower layers.

Content-based routing supports scenarios like API versioning where URL paths indicate API versions routing to different backends, geographic routing where Accept-Language headers influence backend selection, device-specific routing where User-Agent detection routes mobile versus desktop clients differently, and A/B testing where custom headers or cookies control traffic distribution for experimentation.

WebSocket Support:

Azure Front Door supports WebSocket protocol, enabling bidirectional real-time communication between clients and backends. WebSocket connections begin as HTTP requests with Upgrade headers, negotiating protocol change from HTTP to WebSocket. Azure Front Door recognizes these upgrade requests, maintaining connections while forwarding to backends.

WebSocket support includes connection persistence maintaining long-lived connections without timeouts, bidirectional message forwarding in both directions without buffering, and connection closure coordinating shutdown between clients and backends. These capabilities enable real-time applications like chat systems, live dashboards, and gaming.

However, WebSocket connections face challenges with Azure Front Door’s routing model. Session affinity becomes critical, as WebSocket state exists in backend memory. Connection failures or backend health changes may break WebSocket connections, requiring clients to reconnect and re-establish state. Applications should implement reconnection logic and externalize state when possible to improve resilience.

gRPC Support:

Azure Front Door supports gRPC protocol, which uses HTTP/2 as transport. gRPC’s use of HTTP/2 streams with binary Protocol Buffers encoding enables efficient RPC communication. Azure Front Door forwards gRPC requests like standard HTTP/2, maintaining stream semantics and metadata.

gRPC support enables microservice architectures using gRPC for service-to-service communication while exposing services through Azure Front Door. However, gRPC requires HTTP/2, limiting compatibility with older clients. Applications exposing gRPC services must consider client capabilities, potentially providing REST alternatives for broader compatibility.

Layer 7 Load Balancing vs Layer 4:

Layer 7 load balancing provides application awareness at the cost of processing overhead. Azure Front Door must parse HTTP protocols, inspect headers, and potentially buffer request bodies for routing decisions. This processing increases CPU consumption and latency compared to Layer 4 forwarding.

However, the benefits justify costs for HTTP applications. Content-based routing enables sophisticated traffic management, header manipulation provides flexibility for security and customization, protocol conversion allows modernization without backend changes, and caching reduces backend load and improves performance. For HTTP workloads, Layer 7 benefits typically outweigh Layer 4 efficiency advantages.

Azure Front Door’s Premium tier supports Layer 4 pass-through mode for non-HTTP traffic, providing high-performance forwarding without application layer processing. This mode suits protocols like database connections, IoT telemetry, or custom TCP applications where HTTP features are unnecessary.

Cross-Layer Interactions

Azure Front Door’s capabilities emerge from interactions across multiple OSI layers, with cross-layer optimizations providing performance and security benefits.

DDoS Protection Across Layers:

Azure Front Door implements DDoS protection at multiple layers, creating defense in depth. Layer 3/4 protection filters volumetric attacks like UDP floods, SYN floods, and reflection attacks. Network-layer protection operates at Microsoft’s network edge, using scrubbing centers to filter attack traffic before it reaches application infrastructure.

Layer 7 protection filters application-layer attacks like HTTP floods, slowloris attacks, and protocol exploitation. Application-layer protection uses WAF rules, rate limiting, and anomaly detection to identify and block attack traffic. The multi-layer approach handles diverse attack types, from network-level floods to sophisticated application-layer exploitation.

DDoS protection operates automatically without configuration required, though Premium tier provides enhanced detection sensitivity and custom tuning. Protection scales automatically to handle large attacks, leveraging Microsoft’s network capacity to absorb volumetric attacks that would overwhelm individual organization defenses.

TLS/SSL Offloading and Encryption:

TLS offloading at Azure Front Door edge locations provides security and performance benefits. Edge-terminated TLS shortens encrypted connection distances, reducing latency compared to end-to-end encryption to distant backends. TLS offloading also reduces backend CPU consumption by eliminating cryptographic processing.

The TLS implementation supports modern best practices: TLS 1.2 and 1.3 protocols with TLS 1.0 and 1.1 deprecated, strong cipher suites excluding weak encryption, perfect forward secrecy using ephemeral key exchange, OCSP stapling for certificate validation, and SNI for multi-domain support. These features provide strong security while maintaining performance and compatibility.

Backend connections from Azure Front Door can use HTTP or HTTPS depending on configuration. HTTPS backend connections encrypt traffic between Azure Front Door and backends, providing end-to-end encryption when required. However, many deployments use HTTP for backend connections, accepting the tradeoff of Microsoft network trust for improved performance.

Certificate Management and Azure Key Vault Integration:

SSL certificate management integrates with Azure Key Vault for secure storage and automated rotation. Azure Front Door uses managed identities to access Key Vault, eliminating credential storage in configurations. Key Vault integration enables centralized certificate management, with updates automatically applied to Azure Front Door without manual intervention.

The certificate provisioning process involves storage in Key Vault with appropriate access policies, managed identity assignment to Azure Front Door profile, certificate reference in frontend configuration, and automatic renewal monitoring and application. This integration simplifies operations while maintaining security through Key Vault encryption and access control.

MTU and Fragmentation Handling:

Maximum Transmission Unit limitations can impact performance when packet sizes exceed network capabilities. Azure Front Door implements Path MTU Discovery, detecting MTU along network paths to avoid fragmentation. TCP connections negotiate MSS (Maximum Segment Size) during handshakes, limiting segment sizes to prevent fragmentation.

However, MTU issues still arise in complex network environments. VPN tunnels, IPv6 transition mechanisms, and certain cloud networking configurations reduce effective MTU below the standard 1500 bytes. Azure Front Door handles these situations through MSS clamping, reducing segment sizes to accommodate smaller MTUs, fragmentation when necessary, and PMTUD black hole detection recognizing broken PMTUD implementations.

Latency Optimization Through Layer Interaction:

Azure Front Door optimizes latency through coordinated techniques across layers. Layer 3 Anycast routing minimizes network distance, Layer 4 TCP Fast Open eliminates handshake round-trips, Layer 4 connection multiplexing avoids repeated handshakes, Layer 7 caching serves content without backend round-trips, and Layer 7 compression reduces transfer times. These optimizations combine to provide significant performance improvements, with users experiencing faster page loads and better responsiveness.

Latency reduction particularly benefits mobile users on high-latency networks. Eliminating round-trips through caching and connection optimization compensates for cellular network latency, improving mobile user experiences. Azure Front Door’s global PoP distribution ensures mobile users connect to nearby edge locations regardless of location, further reducing latency.

Load Balancing Deep Dive

Load balancing represents one of Azure Front Door’s core capabilities, distributing traffic across multiple backends to improve performance, reliability, and scalability. This section examines load balancing mechanisms in detail, covering algorithms, health monitoring, and failover behaviors.

Global vs Regional Load Balancing

Azure Front Door implements global load balancing, distributing traffic across backends in multiple geographic regions. This global scope distinguishes Azure Front Door from regional load balancers like Azure Application Gateway.

Global Distribution Benefits:

Global load balancing provides several advantages. Geographic distribution places backends near users, reducing latency through proximity. Resilience improves as failures in one region do not affect others, enabling continued service during regional outages. Capacity scaling occurs globally, with traffic distributed to available capacity wherever it exists. Compliance requirements for data residency are satisfied through geographic routing policies.

The global model suits applications serving worldwide user bases, where single-region deployment creates latency and availability limitations. However, global distribution introduces complexity including configuration management across regions, data synchronization between backends, and cost implications of multi-region deployment.

Regional Considerations:

Within global deployment, regional factors influence traffic distribution. Latency-based routing considers network performance to each region, preferring lower latency backends. Geographic preferences can route users to specific regions based on location, supporting compliance or data sovereignty requirements. Priority settings enable primary-secondary patterns where specific regions handle traffic until failures occur.

These regional controls provide flexibility for diverse deployment patterns. Applications can implement active-active with traffic distributed globally, active-passive with traffic normally routed to primary regions, or geographic isolation where users in each region access local backends.

Load Balancing Algorithms

Azure Front Door supports multiple load balancing algorithms, each suited for different scenarios and requirements.

Latency-Based Routing:

Latency-based routing (the default algorithm) monitors backend response times through health probes and active request measurement. Azure Front Door maintains moving averages of latency to each backend, updating values continuously based on observed performance. When routing requests, Azure Front Door selects backends with lowest observed latency, optimizing for responsiveness.

The latency measurement includes network latency between Azure Front Door edge and backend, plus backend processing time for health probe requests. This combined metric reflects actual user experience, incorporating both network and application performance. As backend performance changes due to load, processing changes, or network conditions, latency-based routing adapts automatically.

However, latency-based routing may not distribute traffic evenly if backend capacities differ. Higher-capacity backends may observe higher latency due to increased load, causing Azure Front Door to route traffic elsewhere. This feedback loop can cause oscillation, with traffic shifting between backends based on transient latency variations. Organizations requiring specific traffic distribution should use weighted or priority-based routing instead.

Priority-Based Routing:

Priority-based routing assigns integer priority values to backends, with lower numbers indicating higher priority. Azure Front Door routes all traffic to backends with the lowest priority value among healthy backends. Traffic distributes among backends at the same priority level according to weights.

This algorithm implements active-passive patterns where priority 1 backends serve all traffic as the active set, while priority 2 backends remain passive, only receiving traffic when all priority 1 backends fail. More complex patterns use multiple priority levels for graduated failover, cascading through priority tiers as failures occur.

Priority-based routing provides predictable traffic distribution, with clear primary and secondary roles. However, it underutilizes passive backends during normal operation, wasting capacity. Organizations accepting this tradeoff for clear failover behavior often prefer priority-based routing.

Weighted Round-Robin:

Weighted round-robin distributes traffic proportionally according to backend weight values. Weights represent relative capacity or desired traffic proportion, with higher weights receiving more traffic. For example, backends with weights 1, 1, and 2 receive 25%, 25%, and 50% of traffic respectively.

The implementation maintains request counts to each backend, selecting backends to match configured weight ratios. Unlike latency-based routing, weighted round-robin provides predictable traffic distribution regardless of performance. This predictability suits scenarios like capacity-aware routing where backend sizes differ, gradual migration when shifting traffic between old and new backends, and A/B testing requiring specific traffic splits.

However, weighted round-robin ignores backend health beyond binary healthy/unhealthy states. Backends experiencing degraded performance but still passing health checks continue receiving full traffic allocation, potentially causing poor user experience. Latency-based routing would automatically reduce traffic to degraded backends, providing better automatic adaptation.

Session Affinity: