Technical Autopsy of the Azure Front Door Configuration Failure and Global Service Disruption

A deep technical analysis of the October 2024 Azure Front Door outage that affected 750,000 customer profiles across 300+ edge sites due to asynchronous reference count failures.

On October 29, 2024, Azure Front Door experienced a catastrophic eight and a half hour global outage affecting over 750,000 customer profiles across 300+ edge sites worldwide. The incident began when incompatible metadata changes, generated by customer configurations processed across different control plane versions, propagated throughout the distributed fleet without triggering safety mechanisms.

The root cause was asynchronous reference count leaks in configuration metadata that caused data plane process crashes after successful health validation, bypassing multi-stage protection systems designed to halt bad deployments. The failure exposed critical gaps in Azure Front Door’s configuration guard system, particularly its inability to detect asynchronously manifesting incompatibilities in background cleanup operations.

Recovery required manual intervention to modify the Last Known Good snapshot rather than rollback to previous versions, followed by a four hour cold boot metadata reload across the global fleet. This represents one of Azure’s most impactful incidents, demonstrating how distributed system race conditions can evade even sophisticated deployment safeguards.

What is Azure Front Door and Why It Matters

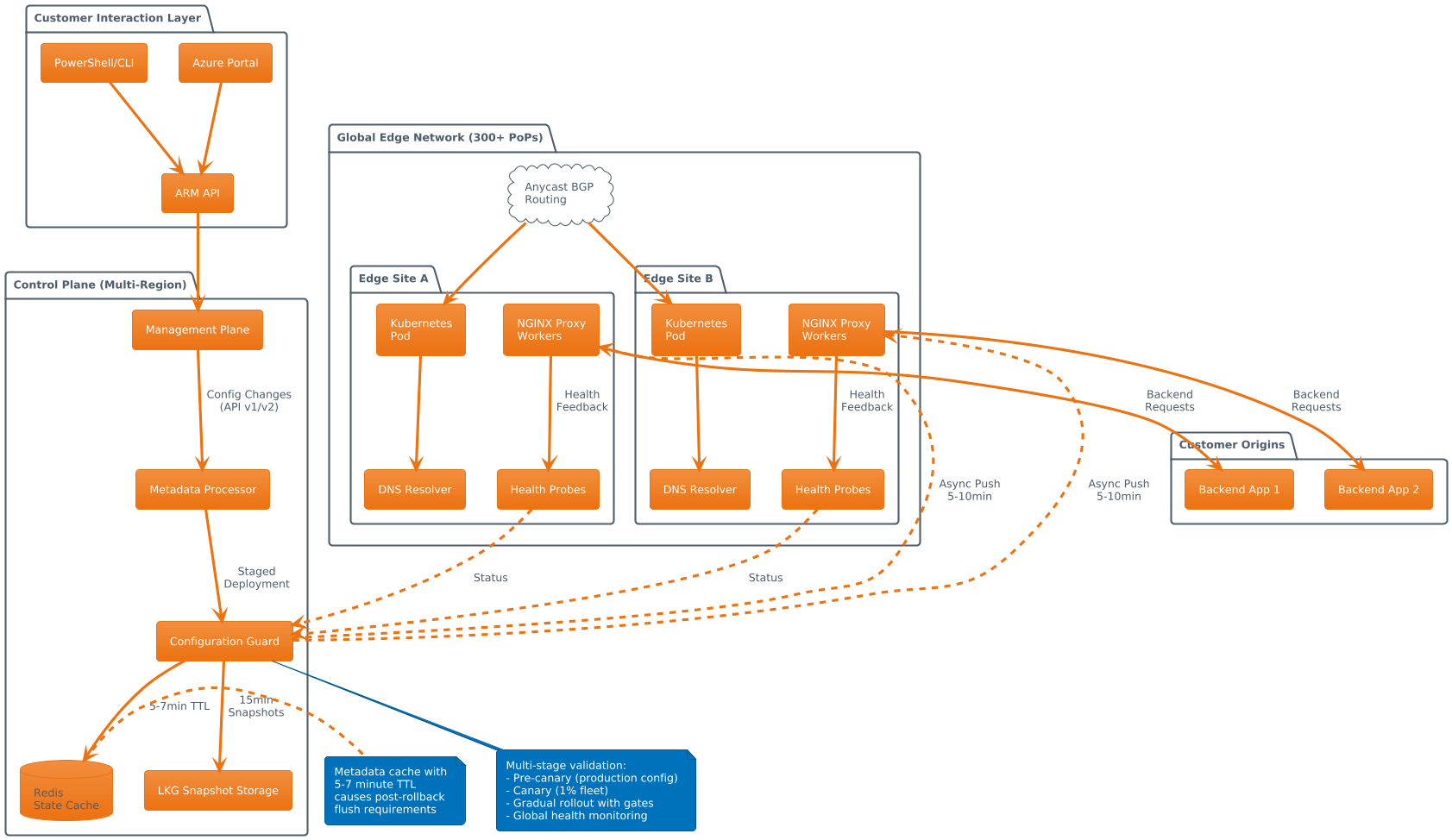

Azure Front Door operates as a globally distributed Layer 7 load balancer spanning 300+ Points of Presence across Azure and third party edge locations. The architecture separates into three distinct planes: management plane for customer interactions through ARM and Portal, control plane for metadata processing and configuration distribution, and data plane for active request serving via NGINX based proxies running in Kubernetes pods.

Each edge site employs anycast BGP routing to attract client traffic to optimal locations based on geographic proximity and health status. Configuration changes propagate globally within 5 to 10 minutes through staged deployments with health feedback loops at each stage.

The service provides WAF protection, DDoS mitigation, TLS termination, and content delivery acceleration for both external customers and critical Microsoft first party services including Azure Portal, Intune, and Entra ID. Edge sites host internal DNS resolution for Azure Front Door managed CNAMEs, creating tight coupling between data plane availability and name resolution. Premium SKUs add Private Link integration and advanced WAF rulesets requiring additional metadata complexity.

Timeline of the Incident

Initial Configuration Changes

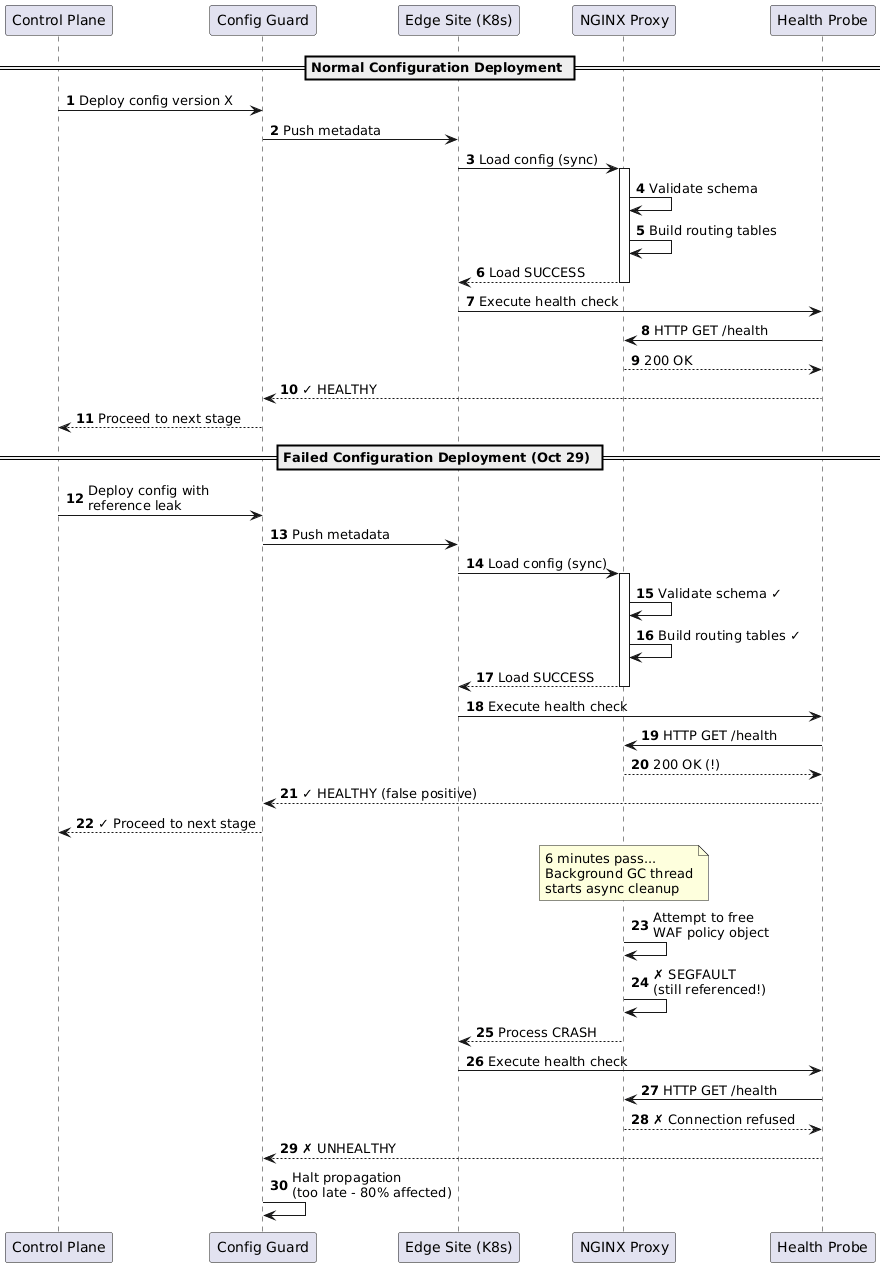

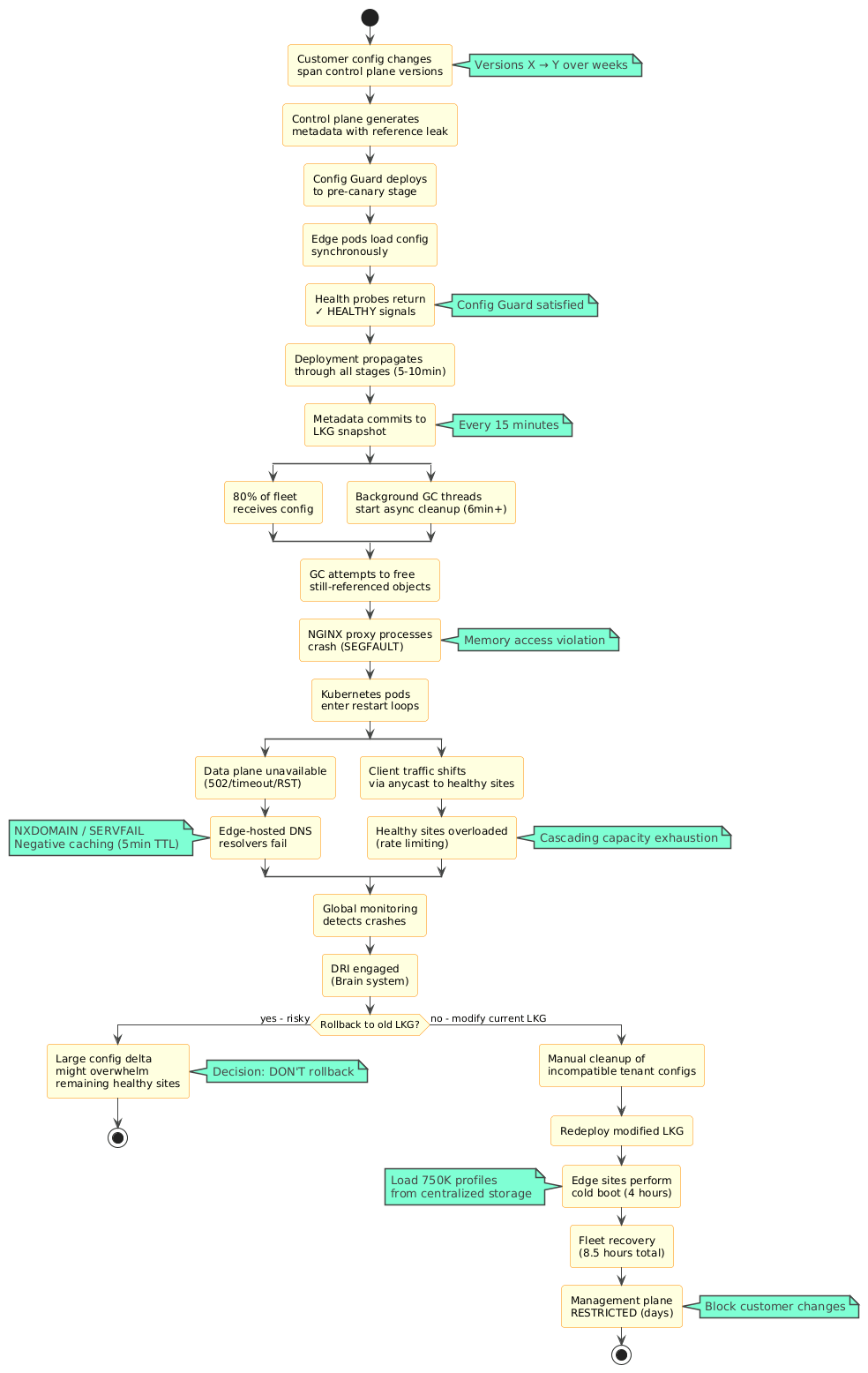

Configuration changes initiated by customers triggered metadata generation in the control plane, where different API versions spanning weeks of control plane releases processed updates to the same profiles. The incompatible metadata containing reference count mismatches propagated through pre-canary validation approximately six minutes after deployment initiation, receiving positive health feedback from edge sites before asynchronous cleanup operations executed.

Cascade Begins

Data plane crashes began cascading across 80% of the global fleet as background reference cleanup processes attempted to free still referenced objects, causing memory access violations. Detection occurred within minutes via distributed probers, triggering automatic DRI engagement through the Brain monitoring system.

Configuration guard systems halted further propagation but after the incompatible changes had already committed to Last Known Good snapshots.

Recovery Phases

Recovery efforts spanned four distinct phases:

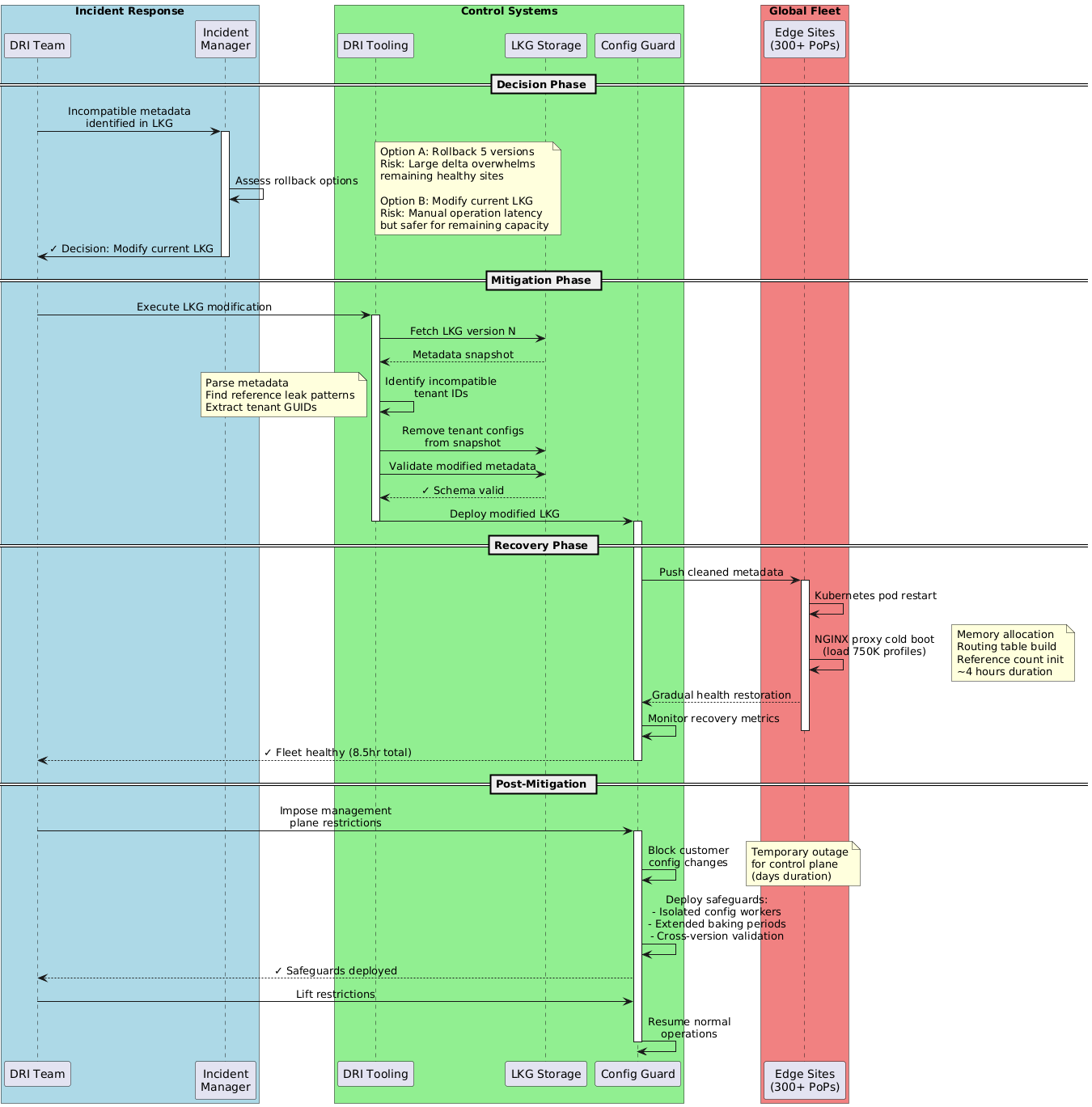

Incident Diagnosis (45 minutes): Teams identified the scope and nature of the configuration incompatibility across the global fleet.

LKG Modification Decision (1 hour): Engineering determined that manual modification of the Last Known Good snapshot was necessary rather than automated rollback.

Manual Metadata Cleanup (2 hours): Specialized tooling identified and removed specific incompatible tenant configurations from the LKG metadata, followed by redeployment initiation.

Fleet Wide Cold Boot (4 hours): Each edge site reloaded 750,000 profile configurations from centralized storage into local memory.

Full mitigation achieved after 8.5 hours with management plane restrictions imposed for subsequent days.

The Root Cause

The failure originated from a subtle interaction between control plane versioning and metadata reference counting. When customers modified Azure Front Door profiles across different control plane releases, the configuration processing logic generated metadata objects with mismatched reference counts for shared resources like WAF policies.

Specifically, control plane version differences caused policy references to be incremented without corresponding tracked dependencies, creating reference leaks invisible to synchronous validation. The configuration guard system, designed to detect crashes through health probes and global fleet monitoring, failed because the actual crashes occurred asynchronously during background garbage collection, not during initial configuration load.

Data plane pods provided positive health feedback during the critical 5 to 10 minute propagation window, allowing the incompatible metadata to progress through all deployment stages and commit to Last Known Good snapshots. The reference cleanup operations executed 6+ minutes post deployment, well after configuration guard checkpoints had passed.

This timing gap between synchronous configuration loading and asynchronous reference cleanup represented a fundamental blind spot in the protection architecture.

How the Configuration Failure Manifested

The metadata incompatibility manifested as dangling pointer failures in the NGINX based proxy processes. When the control plane serialized customer configurations into data plane metadata, it maintained reference counts for shared objects including WAF policies, routing rules, and origin groups to manage memory lifecycle.

Version skew between control plane releases caused these reference counts to diverge. Version X incremented references during profile updates, while Version Y’s garbage collector decremented based on different tracking assumptions.

Data plane pods loaded the metadata successfully, validating schema correctness and routing table integrity, then returned positive acknowledgments to the control plane. However, background cleanup threads operating on 5 to 15 minute intervals attempted to free WAF policy objects still referenced by active routing configurations.

This triggered segmentation faults in the proxy master processes, cascading to worker process failures as the Kubernetes pod entered restart loops. The crashes manifested as immediate connection termination through TCP RST packets, 502 Bad Gateway responses when backend connections existed, and complete request timeouts when edge sites became fully unavailable.

Session affinity using cookie based persistence exacerbated impact by pinning users to failed pods. The asynchronous nature meant health probes showing green status for 6+ minutes post deployment, satisfying configuration guard requirements before catastrophic failures materialized globally.

DNS Resolution and Cascade Effects

Azure Front Door’s architecture hosts authoritative DNS servers on edge sites to provide low latency CNAME resolution for customer domains. When data plane Kubernetes pods crashed, the co-located DNS resolver processes either terminated or became unresponsive, generating NXDOMAIN and SERVFAIL responses.

This created a cascading failure pattern. Client DNS resolvers experiencing failures would retry against other Azure Front Door edge sites via anycast routing, but those sites were experiencing identical crashes. Recursive resolvers implemented negative caching with typical 5 minute TTLs, amplifying the impact beyond data plane recovery timelines.

The DNS failures manifested distinctly from HTTP layer errors. External monitoring tools like ThousandEyes and Down Detector initially attributed issues to DNS infrastructure rather than Azure Front Door specific problems, creating diagnostic confusion.

TLS handshakes dependent on OCSP stapling and certificate chain validation experienced failures when edge sites couldn’t resolve internal dependency endpoints. HTTP/2 multiplexing compounded issues: single connection failures affected multiple concurrent streams, and clients lacked fallback mechanisms to HTTP/1.1 or alternative endpoints.

The cascade intensified as healthy edge sites absorbed traffic from failed peers, overwhelming capacity limits and triggering rate limiting that generated legitimate 429 responses even after partial recovery, creating a multi hour stabilization tail beyond initial mitigation.

Impact on Customers and Services

The outage affected both direct Azure Front Door customers and Microsoft first party services fronted by Azure Front Door for DDoS protection and global distribution. Azure Portal experienced complete unavailability for all users globally, preventing customers from accessing resource health dashboards and incident status pages, creating circular communication failures.

Intune and Entra ID portals became inaccessible, disrupting enterprise identity management and device enrollment workflows. External customers running mission critical applications experienced greater than 90% error rates including e-commerce platforms during peak traffic periods, airline reservation systems requiring real time availability, and SaaS providers with contractual SLA obligations.

Premium SKU customers leveraging Private Link for secure backend connectivity faced compounded failures as edge sites couldn’t establish tunnels to origin Virtual Networks. WAF protected applications became completely exposed when automatic failover to direct origin access wasn’t configured, forcing security conscious customers to choose between availability and protection posture.

The economic impact included direct revenue loss for affected businesses, SLA credit obligations for Azure, and reputational damage across the hyperscaler ecosystem, with industry analysts comparing the incident to historical AWS and GCP control plane failures.

Why This Class of Failure Is Hard to Prevent

Global CDN architectures face inherent tension between rapid configuration propagation required for cache purges and security policy updates and deployment safety. Azure Front Door’s 5 to 10 minute global deployment window exists because customers demand sub-minute activation of WAF rules during active DDoS attacks and immediate cache invalidation for compliance driven content removal.

Implementing traditional staged rollouts spanning hours to days conflicts with operational requirements. The asynchronous reference counting bug represents a class of distributed system race conditions nearly impossible to detect in pre-production. Timing dependencies across control plane versions, background cleanup thread scheduling, and garbage collection intervals only manifest at production scale with specific customer configuration patterns accumulated over weeks.

Configuration guard systems inherently optimize for synchronous crash detection. Probes, health checks, and feedback loops operate on seconds to minutes timescales, while memory lifecycle bugs can manifest on hours to days intervals.

The incident revealed that even sophisticated multi-stage validation including pre-canary, canary, and gradual rollout with health gates cannot protect against bugs that provide positive signals during deployment windows but fail asynchronously afterward.

Autonomous rollback systems, removed in 2023 after incidents where automatic reverts caused cascading failures, would have potentially mitigated this specific case but at the cost of increased false positive rollbacks impacting legitimate customer changes.

Post Incident Actions and Mitigations

Immediate response involved manual modification of the most recent Last Known Good snapshot rather than rollback to earlier versions, avoiding the risk of overwhelming remaining healthy edge sites with configuration deltas spanning multiple LKG generations.

The DRI team used specialized tooling to identify and remove the specific incompatible tenant configurations from the LKG metadata, then triggered redeployment. Recovery required a four hour cold boot as each edge site reloaded 750,000 profile configurations from centralized storage into local memory.

Post mitigation, Azure Front Door management plane operations were blocked globally for multiple days, an unprecedented step imposing control plane outages on customers while engineering teams implemented critical safeguards.

New Protection Mechanisms

Pre-canary stage with production configuration only validation eliminated synthetic data testing that could mask real world incompatibilities. Extended baking periods of 15+ minutes before stage progression allow asynchronous operations to complete and manifest failures within deployment windows.

Isolated configuration processing workers that can crash without affecting active data plane request serving prevent cascading failures. Cross version compatibility testing in the control plane CI/CD pipeline catches reference counting mismatches before production deployment.

Long Term Architectural Changes

Micro-cellular isolation using ingress sharding distributes tenant configurations across 24 to 48 workers per node such that single tenant failures cannot cascade, achieving statistical isolation similar to card shuffling. Recovery time improvements reduced cold boot duration from 4.5 hours to under 1 hour through memory mapped configuration loading, with roadmap targets of 15 minutes through further optimizations.

Lessons for Cloud Architects and Operators

This incident reinforces critical distributed system design principles applicable beyond Azure. Multi-CDN architectures using active-active traffic splitting through DNS level services like NS1 or Route 53, or application level via client side SDKs can maintain availability during provider specific failures, though at significant cost and complexity overhead.

Azure’s recommendation for critical workloads: Azure Traffic Manager fronting origin servers directly as failover, enabling sub-minute DNS updates to bypass Azure Front Door during incidents while accepting temporary loss of WAF protection.

Configuration versioning discipline becomes paramount. APIs should enforce backward compatibility guarantees or explicitly fail incompatible combinations rather than silently generating corrupt metadata.

Health probe design must include asynchronous failure detection through synthetic traffic continuously exercising full request paths including reference counting and cleanup operations, not just synchronous load success.

Chaos engineering practices should inject configuration induced failures by deliberately corrupting metadata in isolated cells, simulating version skew scenarios, and validating automated rollback mechanisms under realistic conditions.

DNS resilience requires multi-provider strategies: geo-distributed authoritative servers on independent infrastructure, aggressive negative TTL minimization, and application layer fallback to IP literals when resolution fails.

Operators should instrument reference counting and memory lifecycle events with high cardinality telemetry, detecting leaks before they manifest as crashes. Most critically, assume configuration management systems will fail and design data planes to survive complete control plane loss through cached state and degraded mode operation.

Conclusion

Azure’s October 29, 2024 Azure Front Door incident exemplifies how subtle race conditions in distributed configuration systems can evade sophisticated safety mechanisms, causing cascading global failures. The engineering response, imposing days of management plane restrictions to deploy comprehensive safeguards including cellular isolation and asynchronous crash protection, demonstrates Microsoft’s commitment to preventing recurrence, though at significant short term customer pain cost.

The incident underscores that even mature hyperscaler platforms face novel failure modes as scale and complexity increase. The architectural improvements implemented post incident, particularly micro-cellular isolation and extended baking periods for asynchronous operations, represent meaningful advances in distributed system safety that benefit the broader cloud infrastructure community.