Understanding Modern GPU Architecture and Parallel Computing

A comprehensive exploration of modern GPU architecture and parallel computing principles, covering SIMD processing, memory hierarchies, and programming models for high-performance computing.

Introduction

Modern graphics processing units (GPUs) represent one of the most fascinating achievements in computer architecture. These devices can perform upwards of 36 trillion calculations per second - a scale so massive that it would require the population of 4,400 Earths working continuously to match this computational power. This article provides a deep technical analysis of GPU architecture, parallel computing paradigms, and practical implementations for leveraging this incredible processing power.

GPU vs CPU Architecture

Architectural Differences

The fundamental distinction between GPUs and CPUs lies in their architectural approach to computation:

- Core Count and Specialization

- GPUs: 10,000+ specialized cores optimized for parallel processing

- CPUs: 8-24 complex cores optimized for sequential processing and task switching

- Processing Paradigm

- GPUs: Single Instruction, Multiple Data (SIMD) / Single Instruction, Multiple Threads (SIMT)

- CPUs: Complex instruction set with branch prediction and out-of-order execution

- Memory Architecture

The Cargo Ship Analogy

Think of a GPU as a massive cargo ship and a CPU as a jumbo jet:

- GPU (Cargo Ship):

- Huge cargo capacity (parallel processing)

- Limited flexibility in routes (specialized instructions)

- Slower but more efficient for bulk operations

- CPU (Jumbo Jet):

- Smaller cargo capacity (sequential processing)

- Highly flexible routing (general-purpose computing)

- Faster for individual operations

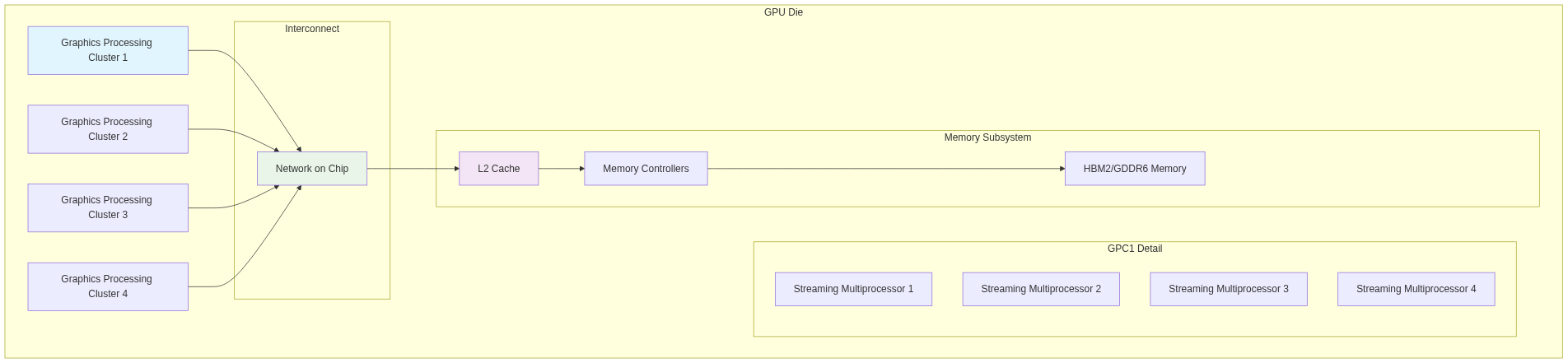

Physical Architecture of Modern GPUs

Hierarchical Organization

Modern GPUs follow a hierarchical organization:

- Graphics Processing Clusters (GPCs)

- Top-level organizational unit

- Contains multiple Streaming Multiprocessors (SMs)

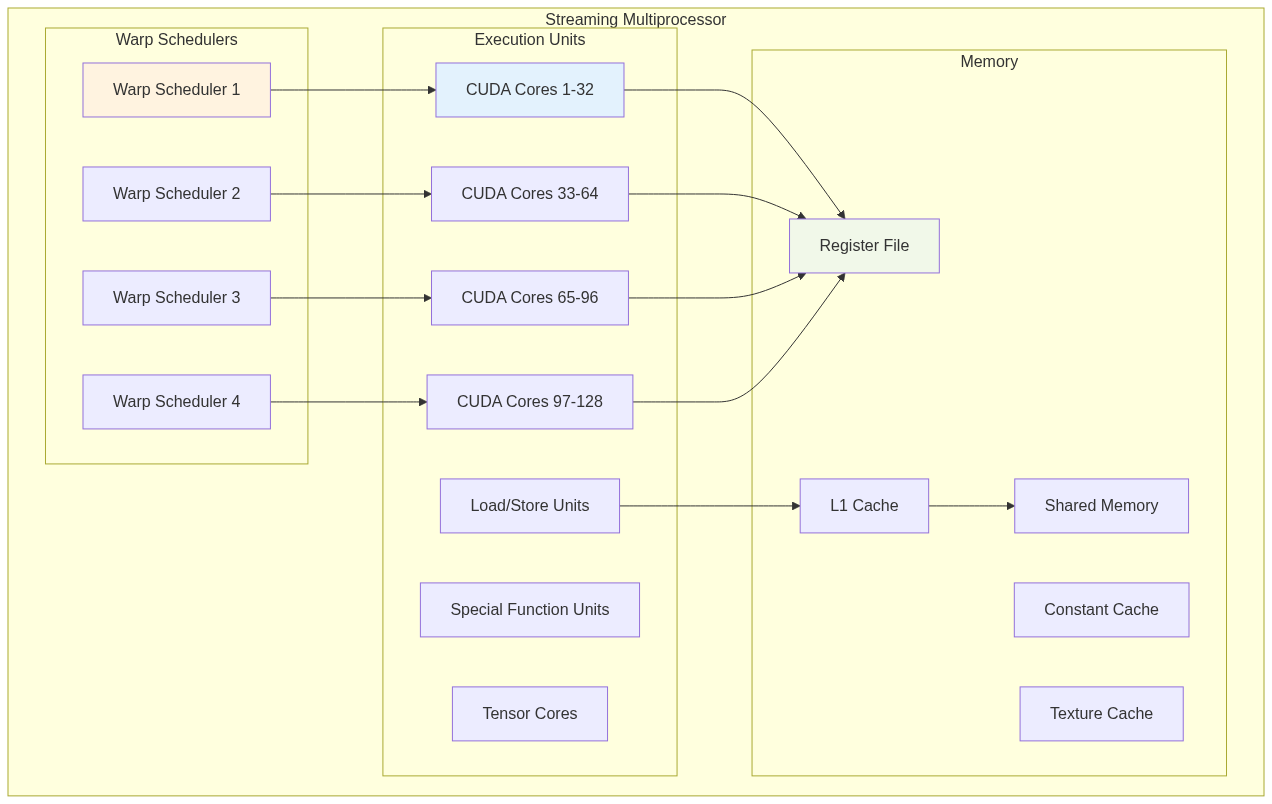

- Streaming Multiprocessors (SMs)

- Contains multiple warps and specialized cores

- Includes shared memory and L1 cache

- Warps

- Group of 32 threads executed simultaneously

- Basic unit of thread execution

- Core Types

- CUDA Cores: Basic arithmetic operations

- Tensor Cores: Matrix operations

- RT Cores: Ray tracing calculations

Implementation Example

Let’s implement a simple program that demonstrates the concept of parallel processing using OpenMP as an analogy for GPU processing:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <omp.h>

#include <time.h>

#define ARRAY_SIZE 1000000

#define NUM_THREADS 8

void parallel_array_operation(float* input, float* output, int size) {

#pragma omp parallel num_threads(NUM_THREADS)

{

int thread_id = omp_get_thread_num();

int chunk_size = size / NUM_THREADS;

int start = thread_id * chunk_size;

int end = (thread_id == NUM_THREADS - 1) ? size : start + chunk_size;

// Simulate GPU-like parallel processing

for (int i = start; i < end; i++) {

// Simple arithmetic operation

output[i] = input[i] * 2.0f + 1.0f;

}

}

}

int main() {

float *input = (float*)malloc(ARRAY_SIZE * sizeof(float));

float *output = (float*)malloc(ARRAY_SIZE * sizeof(float));

// Initialize input array

srand(time(NULL));

for (int i = 0; i < ARRAY_SIZE; i++) {

input[i] = (float)rand() / RAND_MAX;

}

// Measure execution time

double start_time = omp_get_wtime();

parallel_array_operation(input, output, ARRAY_SIZE);

double end_time = omp_get_wtime();

printf("Execution time: %f seconds\n", end_time - start_time);

printf("First 5 results: %f %f %f %f %f\n",

output[0], output[1], output[2], output[3], output[4]);

free(input);

free(output);

return 0;

}

To compile and run this code:

1

2

gcc -fopenmp parallel_processing.c -o parallel_processing

./parallel_processing

The assembly output for the critical section (using gcc -S):

.L3:

movss (%rdi,%rax,4), %xmm0 # Load input value

mulss .LC0(%rip), %xmm0 # Multiply by 2.0

addss .LC1(%rip), %xmm0 # Add 1.0

movss %xmm0, (%rsi,%rax,4) # Store result

addq $1, %rax # Increment counter

cmpq %rdx, %rax # Compare with end

jl .L3 # Loop if not done

Computational Architecture and SIMD/SIMT

SIMD vs SIMT Architecture

SIMD (Single Instruction, Multiple Data)

- Traditional parallel processing model

- All threads execute exactly the same instruction

- Lock-step execution

- Limited flexibility with branching

SIMT (Single Instruction, Multiple Threads)

- Modern GPU architecture

- Threads can diverge and reconverge

- Individual program counters

- Better handling of conditional code

Let’s implement a SIMT-like operation in C:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <pthread.h>

#include <time.h>

#define WARP_SIZE 32

#define NUM_WARPS 4

#define TOTAL_THREADS (WARP_SIZE * NUM_WARPS)

typedef struct {

int thread_id;

float* input;

float* output;

int size;

} ThreadData;

void* simt_thread(void* arg) {

ThreadData* data = (ThreadData*)arg;

int tid = data->thread_id;

int stride = TOTAL_THREADS;

// Simulate SIMT execution with divergent paths

for (int i = tid; i < data->size; i += stride) {

if (data->input[i] > 0.5f) {

// Branch 1: Square the value

data->output[i] = data->input[i] * data->input[i];

} else {

// Branch 2: Double the value

data->output[i] = data->input[i] * 2.0f;

}

}

return NULL;

}

int main() {

const int size = 1024;

float* input = (float*)malloc(size * sizeof(float));

float* output = (float*)malloc(size * sizeof(float));

pthread_t threads[TOTAL_THREADS];

ThreadData thread_data[TOTAL_THREADS];

// Initialize input array

srand(time(NULL));

for (int i = 0; i < size; i++) {

input[i] = (float)rand() / RAND_MAX;

}

// Create threads

for (int i = 0; i < TOTAL_THREADS; i++) {

thread_data[i].thread_id = i;

thread_data[i].input = input;

thread_data[i].output = output;

thread_data[i].size = size;

pthread_create(&threads[i], NULL, simt_thread, &thread_data[i]);

}

// Join threads

for (int i = 0; i < TOTAL_THREADS; i++) {

pthread_join(threads[i], NULL);

}

// Print sample results

printf("Sample results:\n");

for (int i = 0; i < 5; i++) {

printf("Input: %.4f, Output: %.4f\n", input[i], output[i]);

}

free(input);

free(output);

return 0;

}

Memory Hierarchy and Data Transfer

Graphics Memory Architecture

Modern GPUs use sophisticated memory hierarchies:

- GDDR6X Memory

- High bandwidth (1.15 TB/s)

- Multiple voltage levels for encoding

- PAM3 signaling

- Memory Controllers

- Wide memory bus (384-bit)

- Multiple memory channels

- Sophisticated error correction

Let’s implement a memory transfer simulation:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <time.h>

#define CACHE_LINE_SIZE 64

#define L1_CACHE_SIZE (64 * 1024) // 64KB L1 Cache

#define L2_CACHE_SIZE (6 * 1024 * 1024) // 6MB L2 Cache

typedef struct {

unsigned char data[CACHE_LINE_SIZE];

int valid;

unsigned long tag;

} CacheLine;

typedef struct {

CacheLine* lines;

int size;

} Cache;

Cache* create_cache(int size) {

Cache* cache = (Cache*)malloc(sizeof(Cache));

cache->size = size / CACHE_LINE_SIZE;

cache->lines = (CacheLine*)calloc(cache->size, sizeof(CacheLine));

return cache;

}

int simulate_memory_access(Cache* l1_cache, Cache* l2_cache, unsigned long address) {

int l1_index = (address / CACHE_LINE_SIZE) % l1_cache->size;

int l2_index = (address / CACHE_LINE_SIZE) % l2_cache->size;

unsigned long tag = address / CACHE_LINE_SIZE;

// Check L1 Cache

if (l1_cache->lines[l1_index].valid &&

l1_cache->lines[l1_index].tag == tag) {

return 1; // L1 Cache hit

}

// Check L2 Cache

if (l2_cache->lines[l2_index].valid &&

l2_cache->lines[l2_index].tag == tag) {

// L2 Cache hit, copy to L1

l1_cache->lines[l1_index].valid = 1;

l1_cache->lines[l1_index].tag = tag;

memcpy(l1_cache->lines[l1_index].data,

l2_cache->lines[l2_index].data,

CACHE_LINE_SIZE);

return 2; // L2 Cache hit

}

// Cache miss, load from main memory

l2_cache->lines[l2_index].valid = 1;

l2_cache->lines[l2_index].tag = tag;

// Simulate memory load

for (int i = 0; i < CACHE_LINE_SIZE; i++) {

l2_cache->lines[l2_index].data[i] = rand() % 256;

}

// Copy to L1

l1_cache->lines[l1_index].valid = 1;

l1_cache->lines[l1_index].tag = tag;

memcpy(l1_cache->lines[l1_index].data,

l2_cache->lines[l2_index].data,

CACHE_LINE_SIZE);

return 3; // Cache miss

}

int main() {

Cache* l1_cache = create_cache(L1_CACHE_SIZE);

Cache* l2_cache = create_cache(L2_CACHE_SIZE);

srand(time(NULL));

// Simulate memory accesses

int num_accesses = 1000000;

int l1_hits = 0, l2_hits = 0, misses = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < num_accesses; i++) {

unsigned long address = rand() % (1ULL << 32); // 32-bit address space

int result = simulate_memory_access(l1_cache, l2_cache, address);

switch(result) {

case 1: l1_hits++; break;

case 2: l2_hits++; break;

case 3: misses++; break;

}

}

printf("Memory Access Statistics:\n");

printf("L1 Cache Hits: %d (%.2f%%)\n",

l1_hits, (float)l1_hits/num_accesses*100);

printf("L2 Cache Hits: %d (%.2f%%)\n",

l2_hits, (float)l2_hits/num_accesses*100);

printf("Cache Misses: %d (%.2f%%)\n",

misses, (float)misses/num_accesses*100);

free(l1_cache->lines);

free(l1_cache);

free(l2_cache->lines);

free(l2_cache);

return 0;

}

Practical Implementation in C

Understanding GPU architecture is valuable, but let’s also explore how to write code that effectively utilizes these architectural features:

CUDA Programming Example

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

#include <cuda_runtime.h>

#include <stdio.h>

// CUDA kernel for vector addition

__global__ void vectorAdd(float *a, float *b, float *c, int n) {

int idx = blockIdx.x * blockDim.x + threadIdx.x;

if (idx < n) {

c[idx] = a[idx] + b[idx];

}

}

// Host function

int main() {

int n = 1024;

size_t size = n * sizeof(float);

// Allocate host memory

float *h_a = (float*)malloc(size);

float *h_b = (float*)malloc(size);

float *h_c = (float*)malloc(size);

// Initialize input arrays

for (int i = 0; i < n; i++) {

h_a[i] = i;

h_b[i] = i * 2;

}

// Allocate device memory

float *d_a, *d_b, *d_c;

cudaMalloc(&d_a, size);

cudaMalloc(&d_b, size);

cudaMalloc(&d_c, size);

// Copy data to device

cudaMemcpy(d_a, h_a, size, cudaMemcpyHostToDevice);

cudaMemcpy(d_b, h_b, size, cudaMemcpyHostToDevice);

// Launch kernel

int threadsPerBlock = 256;

int blocksPerGrid = (n + threadsPerBlock - 1) / threadsPerBlock;

vectorAdd<<<blocksPerGrid, threadsPerBlock>>>(d_a, d_b, d_c, n);

// Copy result back to host

cudaMemcpy(h_c, d_c, size, cudaMemcpyDeviceToHost);

// Verify result

for (int i = 0; i < 10; i++) {

printf("c[%d] = %.2f\n", i, h_c[i]);

}

// Free memory

free(h_a); free(h_b); free(h_c);

cudaFree(d_a); cudaFree(d_b); cudaFree(d_c);

return 0;

}

OpenCL Example

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

#include <CL/cl.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

const char* kernelSource =

"__kernel void vectorAdd(__global float* a, __global float* b, __global float* c, int n) {\n"

" int idx = get_global_id(0);\n"

" if (idx < n) {\n"

" c[idx] = a[idx] + b[idx];\n"

" }\n"

"}\n";

int main() {

// Platform and device setup

cl_platform_id platform;

cl_device_id device;

cl_context context;

cl_command_queue queue;

cl_program program;

cl_kernel kernel;

// Get platform and device

clGetPlatformIDs(1, &platform, NULL);

clGetDeviceIDs(platform, CL_DEVICE_TYPE_GPU, 1, &device, NULL);

// Create context and command queue

context = clCreateContext(NULL, 1, &device, NULL, NULL, NULL);

queue = clCreateCommandQueue(context, device, 0, NULL);

// Create program and kernel

program = clCreateProgramWithSource(context, 1, &kernelSource, NULL, NULL);

clBuildProgram(program, 1, &device, NULL, NULL, NULL);

kernel = clCreateKernel(program, "vectorAdd", NULL);

// Buffer creation and kernel execution would follow...

return 0;

}

Advanced Topics

Tensor Cores and Matrix Operations

Tensor cores are specialized processing units designed for matrix multiplication and addition operations. Here’s a simple matrix multiplication implementation:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <time.h>

#include <omp.h>

#define MATRIX_SIZE 1024

#define BLOCK_SIZE 32

void tensor_core_simulation(float* A, float* B, float* C, float* D,

int M, int N, int K) {

#pragma omp parallel for collapse(2)

for (int i = 0; i < M; i += BLOCK_SIZE) {

for (int j = 0; j < N; j += BLOCK_SIZE) {

float temp[BLOCK_SIZE][BLOCK_SIZE] = {0};

// Matrix multiplication in blocks

for (int k = 0; k < K; k += BLOCK_SIZE) {

for (int bi = 0; bi < BLOCK_SIZE; bi++) {

for (int bj = 0; bj < BLOCK_SIZE; bj++) {

float sum = 0.0f;

for (int bk = 0; bk < BLOCK_SIZE; bk++) {

sum += A[(i+bi)*K + (k+bk)] *

B[(k+bk)*N + (j+bj)];

}

temp[bi][bj] += sum;

}

}

}

// Add bias and store result

for (int bi = 0; bi < BLOCK_SIZE; bi++) {

for (int bj = 0; bj < BLOCK_SIZE; bj++) {

D[(i+bi)*N + (j+bj)] =

temp[bi][bj] + C[(i+bi)*N + (j+bj)];

}

}

}

}

}

}

int main() {

float *A, *B, *C, *D;

// Allocate matrices

A = (float*)malloc(MATRIX_SIZE * MATRIX_SIZE * sizeof(float));

B = (float*)malloc(MATRIX_SIZE * MATRIX_SIZE * sizeof(float));

C = (float*)malloc(MATRIX_SIZE * MATRIX_SIZE * sizeof(float));

D = (float*)malloc(MATRIX_SIZE * MATRIX_SIZE * sizeof(float));

// Initialize matrices with random values

srand(time(NULL));

for (int i = 0; i < MATRIX_SIZE * MATRIX_SIZE; i++) {

A[i] = (float)rand() / RAND_MAX;

B[i] = (float)rand() / RAND_MAX;

C[i] = (float)rand() / RAND_MAX;

}

// Measure execution time

double start_time = omp_get_wtime();

tensor_core_simulation(A, B, C, D, MATRIX_SIZE, MATRIX_SIZE, MATRIX_SIZE);

double end_time = omp_get_wtime();

printf("Matrix multiplication completed in %.3f seconds\n",

end_time - start_time);

// Print sample results

printf("Sample output (top-left 2x2 corner):\n");

for (int i = 0; i < 2; i++) {

for (int j = 0; j < 2; j++) {

printf("%.4f ", D[i * MATRIX_SIZE + j]);

}

printf("\n");

}

free(A);

free(B);

free(C);

free(D);

return 0;

}

Ray Tracing Cores

Ray tracing cores handle complex intersection calculations for real-time ray tracing. Here’s a simplified ray-triangle intersection implementation:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <math.h>

#include <omp.h>

typedef struct {

float x, y, z;

} Vector3;

typedef struct {

Vector3 origin;

Vector3 direction;

} Ray;

typedef struct {

Vector3 v0, v1, v2;

} Triangle;

Vector3 subtract(Vector3 a, Vector3 b) {

Vector3 result = {

a.x - b.x,

a.y - b.y,

a.z - b.z

};

return result;

}

Vector3 cross(Vector3 a, Vector3 b) {

Vector3 result = {

a.y * b.z - a.z * b.y,

a.z * b.x - a.x * b.z,

a.x * b.y - a.y * b.x

};

return result;

}

float dot(Vector3 a, Vector3 b) {

return a.x * b.x + a.y * b.y + a.z * b.z;

}

// Möller–Trumbore intersection algorithm

int ray_triangle_intersection(Ray ray, Triangle triangle, float* t) {

const float EPSILON = 0.0000001;

Vector3 edge1 = subtract(triangle.v1, triangle.v0);

Vector3 edge2 = subtract(triangle.v2, triangle.v0);

Vector3 h = cross(ray.direction, edge2);

float a = dot(edge1, h);

if (a > -EPSILON && a < EPSILON)

return 0; // Ray is parallel to triangle

float f = 1.0 / a;

Vector3 s = subtract(ray.origin, triangle.v0);

float u = f * dot(s, h);

if (u < 0.0 || u > 1.0)

return 0;

Vector3 q = cross(s, edge1);

float v = f * dot(ray.direction, q);

if (v < 0.0 || u + v > 1.0)

return 0;

*t = f * dot(edge2, q);

return *t > EPSILON;

}

int main() {

const int NUM_RAYS = 1000000;

const int NUM_TRIANGLES = 1000;

// Create sample rays and triangles

Ray* rays = (Ray*)malloc(NUM_RAYS * sizeof(Ray));

Triangle* triangles = (Triangle*)malloc(NUM_TRIANGLES * sizeof(Triangle));

// Initialize random rays and triangles

srand(time(NULL));

for (int i = 0; i < NUM_RAYS; i++) {

rays[i].origin = (Vector3){

(float)rand() / RAND_MAX,

(float)rand() / RAND_MAX,

(float)rand() / RAND_MAX

};

rays[i].direction = (Vector3){

(float)rand() / RAND_MAX - 0.5f,

(float)rand() / RAND_MAX - 0.5f,

(float)rand() / RAND_MAX - 0.5f

};

}

for (int i = 0; i < NUM_TRIANGLES; i++) {

triangles[i].v0 = (Vector3){

(float)rand() / RAND_MAX,

(float)rand() / RAND_MAX,

(float)rand() / RAND_MAX

};

triangles[i].v1 = (Vector3){

(float)rand() / RAND_MAX,

(float)rand() / RAND_MAX,

(float)rand() / RAND_MAX

};

triangles[i].v2 = (Vector3){

(float)rand() / RAND_MAX,

(float)rand() / RAND_MAX,

(float)rand() / RAND_MAX

};

}

// Perform intersection tests

int total_intersections = 0;

double start_time = omp_get_wtime();

#pragma omp parallel for reduction(+:total_intersections)

for (int i = 0; i < NUM_RAYS; i++) {

for (int j = 0; j < NUM_TRIANGLES; j++) {

float t;

if (ray_triangle_intersection(rays[i], triangles[j], &t)) {

total_intersections++;

}

}

}

double end_time = omp_get_wtime();

printf("Processed %d ray-triangle intersections\n",

NUM_RAYS * NUM_TRIANGLES);

printf("Found %d intersections\n", total_intersections);

printf("Time taken: %.3f seconds\n", end_time - start_time);

free(rays);

free(triangles);

return 0;

}

Visualization of Architecture

To better understand GPU architecture, here’s a visual representation of the key components:

SM (Streaming Multiprocessor) Internal Architecture

This visualization shows how the hierarchical organization enables massive parallelism while maintaining efficient data flow and resource utilization.

Further Reading

For deeper understanding of GPU architecture and parallel computing:

- NVIDIA CUDA Programming Guide

- “GPU Gems” series by NVIDIA

- “Heterogeneous Computing with OpenCL” by Gaster et al.

- “Programming Massively Parallel Processors” by Kirk and Hwu

- “Real-Time Rendering” by Akenine-Möller et al.

Conclusion

Modern GPU architecture represents a fascinating convergence of parallel processing capabilities, sophisticated memory hierarchies, and specialized computational units. Through our detailed exploration of physical architecture, computational models, and practical implementations, we’ve seen how GPUs achieve their remarkable performance in specific workloads.

Key takeaways:

- GPUs excel at parallel processing through their SIMD/SIMT architecture.

- Memory hierarchy and bandwidth are crucial for GPU performance.

- Specialized cores (Tensor, RT) enable efficient handling of specific computations.

- Modern GPU architecture continues to evolve, particularly in areas like AI and ray tracing.

The future of GPU architecture promises even more exciting developments, particularly in areas like real-time ray tracing, AI acceleration, and general-purpose computing. Understanding these fundamentals provides a solid foundation for leveraging these powerful processors in various applications, from gaming to scientific computing.