Day 06: Deep Dive into Context Switching Processes - Low-Level Implementation Details

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Understanding Context Switching

- Definition and Basics

- Why Context Switching is Necessary

- Components Involved

- Context Switch Mechanism

- Hardware Support

- Processor State

- Memory Management During Context Switch

- Implementation Details

- Context Switch Steps

- Data Structures

- Kernel Implementation

- Performance Considerations

- Context Switch Cost

- Optimization Techniques

- Code Implementation

- Context Switch Simulation

- Performance Measurement

- Real-world Examples

- Further Reading

- Conclusion

- References

1. Introduction

Context switching is a fundamental concept in operating systems that enables multitasking by allowing multiple processes to share a single CPU. This article provides an in-depth exploration of context switching mechanisms, implementation details, and performance implications.

2. Understanding Context Switching

Definition and Basics

A context switch is the process of storing and restoring the state (context) of a process so that execution can be resumed from the same point at a later time. This enables time-sharing of CPU resources among multiple processes.

Why Context Switching is Necessary

- Multitasking: Allows multiple processes to run concurrently

- Resource Sharing: Enables efficient use of CPU resources

- Process Isolation: Maintains security and stability

- Real-time Response: Ensures timely handling of high-priority tasks

Components Involved

- Process Control Block (PCB)

- Contains process state information

- Registers

- Program counter

- Stack pointer

- Memory management information

- I/O status information

- CPU Registers

- General-purpose registers

- Program counter

- Stack pointer

- Status registers

3. Context Switch Mechanism

Hardware Support

Modern processors provide specific instructions and features to support context switching:

// Example of hardware-specific register definitions

typedef struct {

uint32_t r0;

uint32_t r1;

uint32_t r2;

uint32_t r3;

uint32_t sp;

uint32_t lr;

uint32_t pc;

uint32_t psr;

} hw_context_t;

Processor State

The processor state includes:

- User-mode registers

- Control registers

- Memory management registers

- Floating-point state

Memory Management During Context Switch

struct mm_struct {

pgd_t* pgd; // Page Global Directory

unsigned long start_code; // Start of code segment

unsigned long end_code; // End of code segment

unsigned long start_data; // Start of data segment

unsigned long end_data; // End of data segment

unsigned long start_brk; // Start of heap

unsigned long brk; // Current heap end

unsigned long start_stack; // Start of stack

};

4. Implementation Details

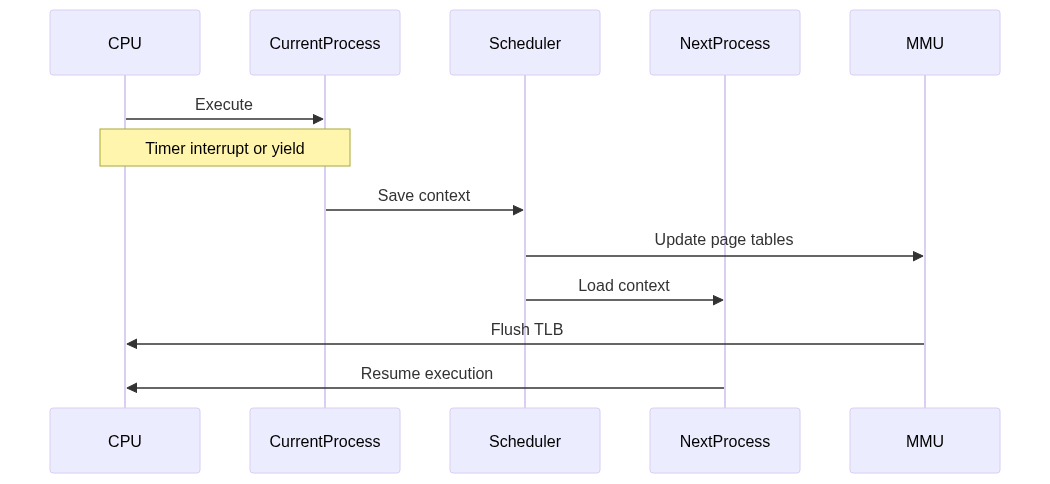

Context Switch Steps

- Save current process state

- Select next process

- Update memory management structures

- Restore new process state

Here’s a simplified implementation:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <ucontext.h>

#define STACK_SIZE 8192

typedef struct {

ucontext_t context;

int id;

} Process;

void function1(void) {

printf("Process 1 executing\n");

}

void function2(void) {

printf("Process 2 executing\n");

}

void context_switch(Process* curr_process, Process* next_process) {

swapcontext(&curr_process->context, &next_process->context);

}

int main() {

Process p1, p2;

char stack1[STACK_SIZE], stack2[STACK_SIZE];

// Initialize process 1

getcontext(&p1.context);

p1.context.uc_stack.ss_sp = stack1;

p1.context.uc_stack.ss_size = STACK_SIZE;

p1.context.uc_link = NULL;

p1.id = 1;

makecontext(&p1.context, function1, 0);

// Initialize process 2

getcontext(&p2.context);

p2.context.uc_stack.ss_sp = stack2;

p2.context.uc_stack.ss_size = STACK_SIZE;

p2.context.uc_link = NULL;

p2.id = 2;

makecontext(&p2.context, function2, 0);

// Perform context switches

printf("Starting context switching demonstration\n");

context_switch(&p1, &p2);

context_switch(&p2, &p1);

return 0;

}

Data Structures

struct task_struct {

volatile long state; // Process state

void *stack; // Stack pointer

unsigned int flags; // Process flags

struct mm_struct *mm; // Memory descriptor

struct thread_struct thread; // Thread information

pid_t pid; // Process ID

struct task_struct *parent; // Parent process

};

Kernel Implementation

The kernel maintains a scheduler that decides which process to run next:

struct scheduler {

struct task_struct *current;

struct list_head runqueue;

unsigned long switches; // Number of context switches

};

5. Performance Considerations

Context Switch Cost

Factors affecting context switch overhead:

- CPU Architecture

- Register count

- Pipeline depth

- Cache organization

- Memory System

- TLB flush requirements

- Cache effects

- Working set size

- Operating System

- Scheduler complexity

- Process priority handling

- Resource management

Optimization Techniques

- Process Affinity

```c

#define _GNU_SOURCE

#include

void set_cpu_affinity(int cpu_id) { cpu_set_t cpuset; CPU_ZERO(&cpuset); CPU_SET(cpu_id, &cpuset); sched_setaffinity(0, sizeof(cpu_set_t), &cpuset); }

2. **TLB Optimization**

```c

// Example of TLB optimization code

static inline void flush_tlb_single(unsigned long addr) {

asm volatile("invlpg (%0)" ::"r" (addr) : "memory");

}

6. Code Implementation

Here’s a complete example that demonstrates context switching with performance measurement:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <time.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <sys/time.h>

#define NUM_SWITCHES 1000

typedef struct {

struct timespec start_time;

struct timespec end_time;

long long total_time;

} timing_info_t;

void measure_context_switch_overhead(timing_info_t *timing) {

pid_t pid;

int pipe_fd[2];

char buf[1];

pipe(pipe_fd);

clock_gettime(CLOCK_MONOTONIC, &timing->start_time);

pid = fork();

if (pid == 0) { // Child process

for (int i = 0; i < NUM_SWITCHES; i++) {

read(pipe_fd[0], buf, 1);

write(pipe_fd[1], "x", 1);

}

exit(0);

} else { // Parent process

for (int i = 0; i < NUM_SWITCHES; i++) {

write(pipe_fd[1], "x", 1);

read(pipe_fd[0], buf, 1);

}

}

clock_gettime(CLOCK_MONOTONIC, &timing->end_time);

timing->total_time = (timing->end_time.tv_sec - timing->start_time.tv_sec) * 1000000000LL +

(timing->end_time.tv_nsec - timing->start_time.tv_nsec);

}

int main() {

timing_info_t timing;

printf("Measuring context switch overhead...\n");

measure_context_switch_overhead(&timing);

printf("Average context switch time: %lld ns\n",

timing.total_time / (NUM_SWITCHES * 2));

return 0;

}

7. Real-world Examples

Let’s look at how context switching is implemented in real operating systems:

- Linux Kernel

/* * context_switch - switch to the new MM and the new thread's register state. */ static __always_inline struct rq * context_switch(struct rq *rq, struct task_struct *prev, struct task_struct *next) { struct mm_struct *mm, *oldmm; prepare_task_switch(rq, prev, next); mm = next->mm; oldmm = prev->active_mm; /* Switch MMU context if needed */ if (!mm) { next->active_mm = oldmm; atomic_inc(&oldmm->mm_count); enter_lazy_tlb(oldmm, next); } else switch_mm(oldmm, mm, next); /* Switch FPU context */ switch_fpu_context(prev, next); /* Switch CPU context */ switch_to(prev, next, prev); return finish_task_switch(prev); }

8. Further Reading

- “Understanding the Linux Kernel” by Daniel P. Bovet and Marco Cesati

- “Operating Systems: Three Easy Pieces” by Remzi H. Arpaci-Dusseau

- “Modern Operating Systems” by Andrew S. Tanenbaum

- Linux Kernel Documentation: Link

9. Conclusion

Context switching is a crucial mechanism that enables modern operating systems to provide multitasking capabilities. Understanding its implementation details and performance implications is essential for system programmers and operating system developers. While context switching introduces overhead, various optimization techniques can help minimize its impact on system performance.

10. References

- Aas, J. (2005). Understanding the Linux 2.6.8.1 CPU Scheduler. Silicon Graphics International.

- Love, R. (2010). Linux Kernel Development (3rd ed.). Addison-Wesley Professional.

- Intel Corporation. (2021). Intel® 64 and IA-32 Architectures Software Developer’s Manual.

- McKenney, P. E. (2020). Is Parallel Programming Hard, And, If So, What Can You Do About It?

- Vahalia, U. (1996). Unix Internals: The New Frontiers. Prentice Hall.