Day 12: Mutex and Semaphores - Advanced Synchronization Mechanisms in Concurrent Programming

Table of Contents

- Introduction to Synchronization

- Understanding Mutex

- Semaphores: A Comprehensive Overview

- Mutex vs Semaphores

- Advanced Implementation Strategies

- Practical Code Examples

- Performance Considerations

- Common Pitfalls and Best Practices

- Theoretical Foundations

- Real-world Applications

- References and Further Reading

- Conclusion

Introduction to Synchronization

Synchronization is the cornerstone of concurrent programming, representing a sophisticated mechanism that ensures orderly and predictable interaction between multiple threads or processes. In the complex landscape of modern computing, where parallel processing has become the norm, synchronization techniques provide a critical framework for managing shared resources, preventing data races, and maintaining system integrity.

At its core, synchronization addresses the fundamental challenge of coordinating access to shared resources in a multithreaded environment. When multiple threads attempt to access and modify the same data simultaneously, unpredictable and potentially catastrophic results can occur. Without proper synchronization, a computer system can experience data corruption, inconsistent states, and catastrophic failures that compromise the entire application’s reliability.

The need for synchronization emerges from the inherent complexity of concurrent systems. Modern processors can execute multiple threads simultaneously, and these threads may compete for access to common resources such as memory, file systems, network connections, and hardware devices. Each thread operates with its own execution context, potentially unaware of the actions of other concurrent threads. This independence, while powerful, creates a potential minefield of synchronization challenges.

Understanding Mutex (Mutual Exclusion)

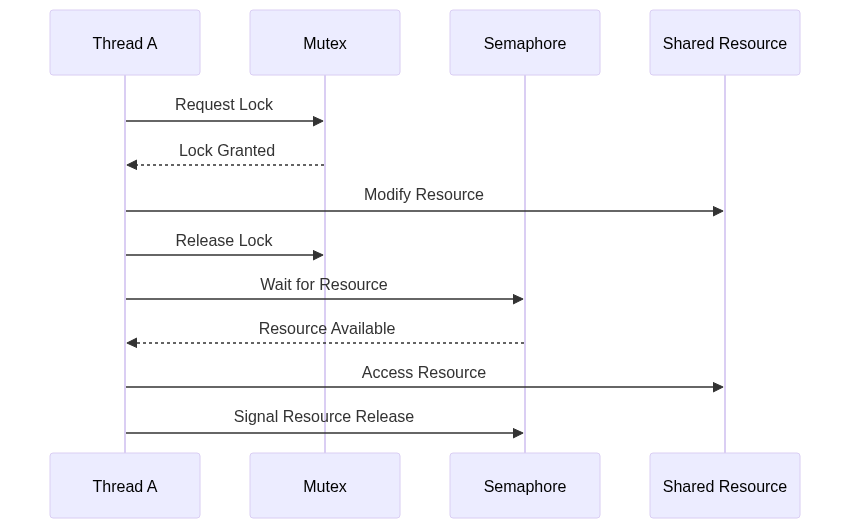

A mutex, short for mutual exclusion, represents a fundamental synchronization primitive designed to provide exclusive access to a shared resource. Think of a mutex as a digital lock that ensures only one thread can enter a critical section of code at any given moment. This mechanism prevents multiple threads from simultaneously modifying shared data, which could lead to inconsistent or corrupted states.

The operational principle of a mutex is elegantly simple yet profoundly powerful. When a thread wants to access a shared resource, it first attempts to acquire the mutex. If the mutex is available, the thread gains exclusive access and can proceed with its operations. Should another thread attempt to acquire the same mutex while it’s already locked, that thread will be blocked, waiting until the first thread releases the mutex.

Mutex implementations typically involve complex low-level mechanisms that interact directly with the operating system’s scheduling and thread management components. Modern operating systems provide efficient mutex primitives that minimize overhead and maximize performance. These implementations often leverage hardware-specific instructions to ensure atomic operations, reducing the performance penalty associated with synchronization.

One critical characteristic of mutexes is their ownership semantics. The thread that acquires a mutex is responsible for releasing it. This design prevents potential deadlocks and ensures that resources are properly managed. Most mutex implementations include error-checking mechanisms that can detect and prevent scenarios like double-locking or attempting to release a mutex that wasn’t acquired.

Semaphores: A Comprehensive Overview

Semaphores represent a more flexible and sophisticated synchronization mechanism compared to traditional mutexes. While a mutex is essentially a binary lock, a semaphore can manage access to multiple resources simultaneously, making it a more versatile synchronization tool.

At its fundamental level, a semaphore maintains an internal counter that represents the number of available resources. Threads can perform two primary operations on a semaphore: wait (decrement the counter) and signal (increment the counter). When the semaphore’s counter reaches zero, subsequent threads attempting to acquire the semaphore will be blocked until resources become available.

There are two primary types of semaphores: binary semaphores and counting semaphores. A binary semaphore functions similarly to a mutex, allowing only two states - locked and unlocked. Counting semaphores, however, can manage multiple resource instances, providing a more nuanced approach to resource allocation.

Semaphores excel in scenarios requiring complex synchronization patterns. For instance, they can effectively manage producer-consumer problems, where multiple threads need to coordinate access to a shared buffer. By carefully managing the semaphore’s counter, developers can ensure that producers don’t overflow the buffer and consumers don’t attempt to read from an empty buffer.

Mutex vs Semaphores: A Comparative Analysis

The distinction between mutex and semaphores goes beyond their technical implementation. A mutex is fundamentally about exclusive access and ownership, creating a strict, controlled environment for resource modification. When a thread acquires a mutex, it gains complete, uninterrupted access to a critical section, ensuring data integrity through isolation.

Semaphores, conversely, provide a more dynamic resource management approach. They don’t inherently enforce ownership or exclusive access but instead focus on managing resource availability. A semaphore can allow multiple threads to access resources concurrently, subject to predefined limits. This flexibility makes semaphores particularly useful in scenarios with complex resource allocation requirements.

Performance considerations further differentiate these synchronization mechanisms. Mutexes typically offer lower overhead for uncontended locks, making them ideal for protecting small, quickly accessed critical sections. Semaphores introduce slightly more complexity but provide greater flexibility in managing multiple resource instances.

Practical Implementation Example

#include <stdio.h>

#include <pthread.h>

#include <semaphore.h>

#define BUFFER_SIZE 10

#define PRODUCER_COUNT 3

#define CONSUMER_COUNT 2

typedef struct {

int data[BUFFER_SIZE];

int count;

pthread_mutex_t mutex;

sem_t empty_slots;

sem_t filled_slots;

} SharedBuffer;

SharedBuffer buffer = {0};

void initialize_buffer(SharedBuffer* buf) {

buf->count = 0;

pthread_mutex_init(&buf->mutex, NULL);

sem_init(&buf->empty_slots, 0, BUFFER_SIZE);

sem_init(&buf->filled_slots, 0, 0);

}

void produce_item(SharedBuffer* buf, int item) {

// Wait for an empty slot

sem_wait(&buf->empty_slots);

// Acquire mutex to safely modify buffer

pthread_mutex_lock(&buf->mutex);

buf->data[buf->count++] = item;

printf("Produced: %d (Buffer: %d)\n", item, buf->count);

// Release mutex

pthread_mutex_unlock(&buf->mutex);

// Signal that a new item is available

sem_post(&buf->filled_slots);

}

int consume_item(SharedBuffer* buf) {

// Wait for a filled slot

sem_wait(&buf->filled_slots);

// Acquire mutex to safely read from buffer

pthread_mutex_lock(&buf->mutex);

int item = buf->data[--buf->count];

printf("Consumed: %d (Buffer: %d)\n", item, buf->count);

// Release mutex

pthread_mutex_unlock(&buf->mutex);

// Signal that an empty slot is now available

sem_post(&buf->empty_slots);

return item;

}

void* producer_thread(void* arg) {

for (int i = 0; i < 5; i++) {

produce_item(&buffer, i * 100);

}

return NULL;

}

void* consumer_thread(void* arg) {

for (int i = 0; i < 5; i++) {

consume_item(&buffer);

}

return NULL;

}

int main() {

pthread_t producers[PRODUCER_COUNT];

pthread_t consumers[CONSUMER_COUNT];

initialize_buffer(&buffer);

// Create producer and consumer threads

for (int i = 0; i < PRODUCER_COUNT; i++) {

pthread_create(&producers[i], NULL, producer_thread, NULL);

}

for (int i = 0; i < CONSUMER_COUNT; i++) {

pthread_create(&consumers[i], NULL, consumer_thread, NULL);

}

// Wait for all threads to complete

for (int i = 0; i < PRODUCER_COUNT; i++) {

pthread_join(producers[i], NULL);

}

for (int i = 0; i < CONSUMER_COUNT; i++) {

pthread_join(consumers[i], NULL);

}

return 0;

}

Advanced Implementation Strategies

The implementation of mutex and semaphore mechanisms represents a complex interplay between hardware capabilities, operating system design, and software engineering principles. Advanced synchronization strategies go far beyond simple locking mechanisms, diving into sophisticated techniques that address the nuanced challenges of concurrent programming.

One critical advanced strategy involves implementing recursive mutexes, which allow a single thread to acquire the same mutex multiple times without causing deadlock. Traditional mutexes would block a thread attempting to re-acquire a lock it already holds, but recursive mutexes maintain a counter that tracks the number of times a specific thread has acquired the lock. This approach proves particularly useful in scenarios involving nested function calls or recursive algorithms that require repeated access to a critical section.

Priority inheritance represents another sophisticated synchronization technique designed to prevent priority inversion problems. In priority-based scheduling systems, a low-priority thread holding a mutex can prevent a high-priority thread from executing, potentially causing system responsiveness issues. Priority inheritance temporarily elevates the priority of the mutex-holding thread to the highest priority of any thread waiting for that mutex, ensuring that critical resources are released more efficiently.

Error-checking mutex variants provide additional debugging and reliability features. These advanced mutex implementations include runtime checks that detect and report potential synchronization errors, such as attempting to unlock a mutex not currently held or destroying a mutex while threads are waiting. By incorporating these checks, developers can more easily identify and resolve synchronization-related issues during development and testing phases.

Performance Considerations

Performance emerges as a critical consideration in synchronization mechanism design. The overhead introduced by mutex and semaphore operations can significantly impact the overall efficiency of concurrent systems, making it essential to understand the intricate performance characteristics of these synchronization primitives.

Mutex performance varies dramatically based on contention levels. In uncontended scenarios, where multiple threads are not simultaneously attempting to acquire the lock, mutex operations introduce minimal overhead. Modern hardware provides low-level atomic instructions that enable extremely fast lock acquisitions and releases. However, as contention increases, the performance penalty becomes more pronounced, involving context switches and kernel-level scheduling interventions.

The implementation platform plays a crucial role in synchronization performance. Different operating systems and hardware architectures implement mutex and semaphore mechanisms with varying levels of efficiency. Some platforms offer user-space synchronization primitives that minimize kernel interaction, while others rely more heavily on system-call-based synchronization, each approach presenting unique performance trade-offs.

Cache coherency represents another critical performance factor. When multiple threads frequently access and modify shared resources protected by mutexes, the underlying cache synchronization mechanisms can introduce significant performance overhead. Careful design strategies, such as minimizing critical section duration and reducing lock granularity, can help mitigate these performance challenges.

Common Pitfalls and Best Practices

Synchronization programming represents a minefield of potential errors that can lead to catastrophic system failures. Developers must navigate a complex landscape of potential pitfalls, requiring deep understanding and disciplined implementation strategies.

Deadlock represents the most notorious synchronization challenge. This occurs when two or more threads are unable to proceed because each is waiting for the other to release a resource. Preventing deadlocks requires careful lock ordering, implementing timeout mechanisms, and avoiding nested or circular lock dependencies. Some advanced systems implement deadlock detection algorithms that can identify and potentially resolve these situations dynamically.

Resource starvation presents another significant concern. This occurs when a thread is perpetually denied access to a required resource, potentially due to poor scheduling or overly aggressive resource allocation strategies. Implementing fair queueing mechanisms and carefully managing resource access priorities can help mitigate starvation risks.

The principle of minimizing critical section duration emerges as a fundamental best practice. The shorter the time a thread holds a lock, the less likely it is to create performance bottlenecks or increase contention. Developers should strive to perform only absolutely necessary operations within synchronized blocks, moving non-critical computations outside of these protected regions.

Theoretical Foundations

The theoretical underpinnings of synchronization mechanisms trace back to seminal work in concurrent computing, including foundational algorithms developed by computer science pioneers. Peterson’s Algorithm and Dekker’s Algorithm represent early attempts to solve the mutual exclusion problem without specialized hardware support, providing crucial insights into the fundamental challenges of concurrent programming.

Lamport’s Bakery Algorithm offers a particularly elegant solution to the mutual exclusion problem in distributed systems. The algorithm uses a ticket-based approach, where threads obtain numerical tickets and are served in order, ensuring fair access to shared resources without relying on complex hardware instructions.

The theoretical study of synchronization mechanisms extends into distributed computing, exploring how synchronization principles can be applied across networked systems. Concepts like distributed mutual exclusion and consensus algorithms build upon the foundational synchronization techniques developed for single-machine concurrent systems.

Real-world Applications

Synchronization mechanisms find applications across virtually every domain of modern computing. Database connection pooling relies heavily on mutex and semaphore techniques to manage limited database connection resources efficiently. Network servers use these mechanisms to coordinate request handling, ensuring that multiple concurrent connections are processed safely and efficiently.

Real-time systems, such as those used in aerospace, medical devices, and industrial control systems, depend critically on precise synchronization mechanisms. These systems require deterministic behavior and strict resource management, making mutex and semaphore techniques essential for maintaining system reliability and predictability.

Multimedia processing represents another domain where advanced synchronization is crucial. Video and audio processing often involve complex pipelines with multiple threads handling different stages of encoding, decoding, and rendering. Sophisticated synchronization mechanisms ensure smooth, glitch-free media processing.

Conclusion

Mutex and semaphore mechanisms represent far more than simple locking techniques. They embody a sophisticated approach to managing concurrency, providing the fundamental building blocks that enable complex, parallel computing systems. As computing continues to evolve towards increasingly parallel architectures, the principles of synchronization will remain critically important.

The journey through mutex and semaphore mechanisms reveals the delicate balance between hardware capabilities, software design, and theoretical computer science principles. Developers who master these techniques gain the ability to create robust, efficient, and reliable concurrent systems that can harness the full power of modern computing architectures.