Day 16: Logical vs Physical Address Space

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Understanding Address Spaces

- Logical Address Space

- Physical Address Space

- Address Translation Mechanisms

- Memory Management Unit (MMU)

- Segmentation

- Paging Systems

- Address Binding

- Implementation Examples

- Common Challenges and Solutions

- Performance Considerations

- Best Practices

- Conclusion and Future Trends

1. Introduction

The concept of logical versus physical addressing is fundamental to modern operating systems and computer architecture. This separation allows for memory virtualization, process isolation, and efficient resource utilization. Logical addresses, also known as virtual addresses, are references to memory locations as seen by the process, while physical addresses represent the actual location in the hardware memory.

2. Understanding Address Spaces

Logical Address Space

Logical address space represents the conceptual view of memory from a process’s perspective. It provides a contiguous address range starting from zero, regardless of the actual physical memory layout. This abstraction allows processes to be written without knowledge of other processes or physical memory constraints.

Physical Address Space

Physical address space represents the actual hardware memory addresses available in the system. These addresses correspond to real memory locations in RAM and are managed by the operating system to ensure proper allocation and protection.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

#define LOGICAL_MEMORY_SIZE 1024

#define PHYSICAL_MEMORY_SIZE 2048

#define PAGE_SIZE 256

typedef struct {

unsigned int logical_address;

unsigned int physical_address;

int valid;

int protection; // 1: read, 2: write, 3: execute

} AddressMapping;

typedef struct {

char* physical_memory;

AddressMapping* address_map;

int map_size;

int used_physical_memory;

} AddressTranslator;

AddressTranslator* initializeAddressTranslator() {

AddressTranslator* translator = (AddressTranslator*)malloc(sizeof(AddressTranslator));

translator->physical_memory = (char*)malloc(PHYSICAL_MEMORY_SIZE);

memset(translator->physical_memory, 0, PHYSICAL_MEMORY_SIZE);

translator->map_size = LOGICAL_MEMORY_SIZE / PAGE_SIZE;

translator->address_map = (AddressMapping*)malloc(

translator->map_size * sizeof(AddressMapping)

);

for(int i = 0; i < translator->map_size; i++) {

translator->address_map[i].logical_address = i * PAGE_SIZE;

translator->address_map[i].physical_address = 0;

translator->address_map[i].valid = 0;

translator->address_map[i].protection = 0;

}

translator->used_physical_memory = 0;

return translator;

}

// Allocate physical memory and create mapping

int createAddressMapping(AddressTranslator* translator,

unsigned int logical_address,

int protection) {

int page_index = logical_address / PAGE_SIZE;

if(page_index >= translator->map_size) {

printf("Error: Logical address out of bounds\n");

return -1;

}

if(translator->used_physical_memory + PAGE_SIZE > PHYSICAL_MEMORY_SIZE) {

printf("Error: Physical memory full\n");

return -1;

}

translator->address_map[page_index].logical_address = logical_address;

translator->address_map[page_index].physical_address = translator->used_physical_memory;

translator->address_map[page_index].valid = 1;

translator->address_map[page_index].protection = protection;

translator->used_physical_memory += PAGE_SIZE;

return 0;

}

// Translate logical to physical address

unsigned int translateAddress(AddressTranslator* translator,

unsigned int logical_address,

int access_type) {

int page_index = logical_address / PAGE_SIZE;

int offset = logical_address % PAGE_SIZE;

if(page_index >= translator->map_size) {

printf("Error: Logical address out of bounds\n");

return -1;

}

AddressMapping* mapping = &translator->address_map[page_index];

if(!mapping->valid) {

printf("Error: Invalid mapping for logical address 0x%x\n", logical_address);

return -1;

}

if((access_type & mapping->protection) != access_type) {

printf("Error: Access violation for logical address 0x%x\n", logical_address);

return -1;

}

return mapping->physical_address + offset;

}

void printAddressSpace(AddressTranslator* translator) {

printf("\nAddress Space Information:\n");

printf("Logical Memory Size: %d bytes\n", LOGICAL_MEMORY_SIZE);

printf("Physical Memory Size: %d bytes\n", PHYSICAL_MEMORY_SIZE);

printf("Used Physical Memory: %d bytes\n", translator->used_physical_memory);

printf("Page Size: %d bytes\n", PAGE_SIZE);

printf("\nValid Mappings:\n");

for(int i = 0; i < translator->map_size; i++) {

if(translator->address_map[i].valid) {

printf("Logical: 0x%x -> Physical: 0x%x (Protection: %d)\n",

translator->address_map[i].logical_address,

translator->address_map[i].physical_address,

translator->address_map[i].protection);

}

}

}

int main() {

AddressTranslator* translator = initializeAddressTranslator();

createAddressMapping(translator, 0x0000, 3); // RWX

createAddressMapping(translator, 0x0100, 1); // R

createAddressMapping(translator, 0x0200, 2); // W

unsigned int logical_addresses[] = {0x0050, 0x0150, 0x0250};

int access_types[] = {1, 2, 3}; // R, W, RWX

for(int i = 0; i < 3; i++) {

unsigned int physical_address = translateAddress(

translator,

logical_addresses[i],

access_types[i]

);

if(physical_address != -1) {

printf("Translated 0x%x -> 0x%x\n",

logical_addresses[i],

physical_address);

}

}

printAddressSpace(translator);

free(translator->physical_memory);

free(translator->address_map);

free(translator);

return 0;

}

3. Address Translation Mechanisms

Address translation is the process of converting logical addresses to physical addresses. This mechanism involves several components and techniques that ensure efficient and secure memory access. The translation process must be fast as it occurs on every memory reference, which is why modern systems implement hardware support through the Memory Management Unit (MMU).

Here’s the implementation of the address translation mechanism:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

#define TLB_SIZE 16

#define PAGE_TABLE_SIZE 1024

#define PAGE_SIZE 4096

#define OFFSET_BITS 12

#define PAGE_NUMBER_BITS 10

typedef struct {

unsigned int page_number;

unsigned int frame_number;

unsigned int valid;

unsigned int access_time;

} TLBEntry;

typedef struct {

unsigned int frame_number;

unsigned int valid;

unsigned int protection_bits;

} PageTableEntry;

typedef struct {

TLBEntry* tlb;

PageTableEntry* page_table;

unsigned int tlb_size;

unsigned int page_table_size;

unsigned int clock;

} AddressTranslator;

AddressTranslator* initAddressTranslator() {

AddressTranslator* at = (AddressTranslator*)malloc(sizeof(AddressTranslator));

// Initialize TLB

at->tlb = (TLBEntry*)calloc(TLB_SIZE, sizeof(TLBEntry));

at->tlb_size = TLB_SIZE;

// Initialize Page Table

at->page_table = (PageTableEntry*)calloc(PAGE_TABLE_SIZE, sizeof(PageTableEntry));

at->page_table_size = PAGE_TABLE_SIZE;

at->clock = 0;

return at;

}

// Update TLB using LRU replacement

void updateTLB(AddressTranslator* at, unsigned int page_number, unsigned int frame_number) {

int lru_index = 0;

unsigned int min_time = at->tlb[0].access_time;

// Find LRU entry

for(int i = 1; i < at->tlb_size; i++) {

if(at->tlb[i].access_time < min_time) {

min_time = at->tlb[i].access_time;

lru_index = i;

}

}

// Update TLB entry

at->tlb[lru_index].page_number = page_number;

at->tlb[lru_index].frame_number = frame_number;

at->tlb[lru_index].valid = 1;

at->tlb[lru_index].access_time = at->clock++;

}

// Translate logical to physical address

unsigned int translateAddress(AddressTranslator* at, unsigned int logical_address) {

unsigned int page_number = logical_address >> OFFSET_BITS;

unsigned int offset = logical_address & ((1 << OFFSET_BITS) - 1);

unsigned int frame_number = 0;

bool tlb_hit = false;

// Check TLB first

for(int i = 0; i < at->tlb_size; i++) {

if(at->tlb[i].valid && at->tlb[i].page_number == page_number) {

frame_number = at->tlb[i].frame_number;

at->tlb[i].access_time = at->clock++;

tlb_hit = true;

break;

}

}

// If TLB miss, check page table

if(!tlb_hit) {

if(page_number >= at->page_table_size) {

printf("Error: Page number out of bounds\n");

return -1;

}

if(!at->page_table[page_number].valid) {

printf("Error: Page fault for page number %u\n", page_number);

return -1;

}

frame_number = at->page_table[page_number].frame_number;

updateTLB(at, page_number, frame_number);

}

return (frame_number << OFFSET_BITS) | offset;

}

void printTranslationStats(AddressTranslator* at) {

printf("\nAddress Translation Statistics:\n");

printf("TLB Size: %u entries\n", at->tlb_size);

printf("Page Table Size: %u entries\n", at->page_table_size);

printf("Page Size: %u bytes\n", PAGE_SIZE);

printf("Valid TLB Entries:\n");

for(int i = 0; i < at->tlb_size; i++) {

if(at->tlb[i].valid) {

printf("Page %u -> Frame %u (Access Time: %u)\n",

at->tlb[i].page_number,

at->tlb[i].frame_number,

at->tlb[i].access_time);

}

}

}

4. Memory Management Unit (MMU)

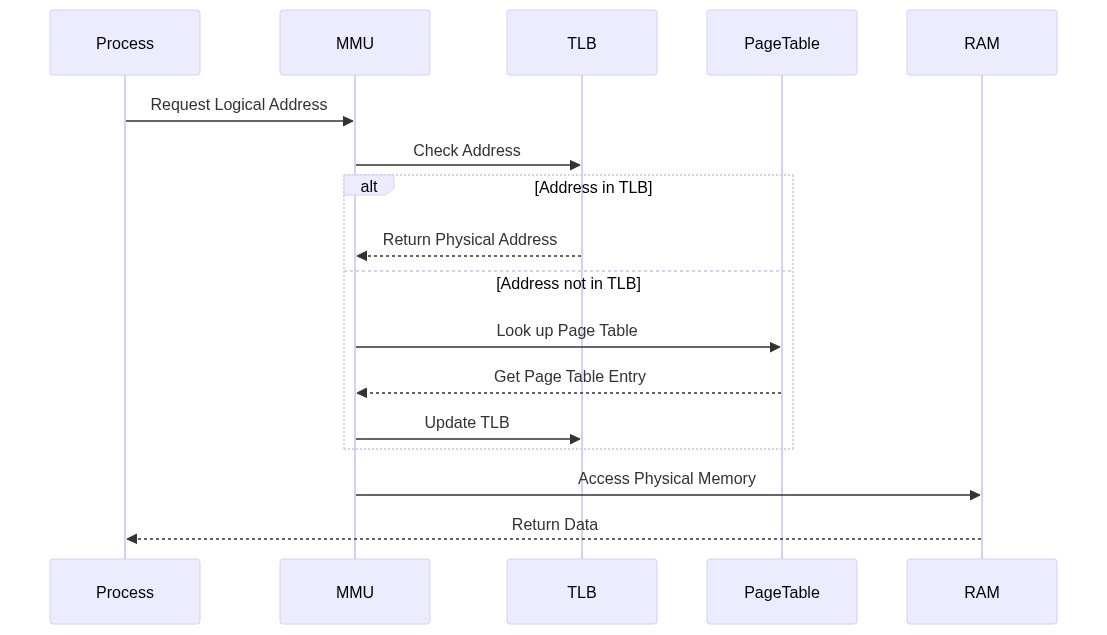

The Memory Management Unit (MMU) is a specialized hardware component responsible for translating virtual addresses generated by the CPU into physical addresses used to access RAM. This translation process is crucial for memory virtualization, allowing multiple processes to share physical memory without interfering with each other. The MMU uses page tables (and often a Translation Lookaside Buffer or TLB for speed) to perform this mapping. When a virtual address is generated, the MMU extracts the page number and offset. It then consults the page table to find the corresponding frame number in physical memory. The frame number is combined with the offset to create the final physical address.

The MMU is a hardware component that handles address translation.

Beyond address translation, the MMU also plays a critical role in memory protection. It enforces access permissions defined by the operating system, preventing unauthorized access to memory regions. This ensures that a process cannot access memory belonging to another process or the operating system itself, enhancing system stability and security. The MMU can detect violations such as a process attempting to write to read-only memory or access memory outside its allocated range, triggering exceptions that the operating system can handle.

5. Segmentation

Segmentation is a memory management technique that divides a program’s address space into logical segments, each representing a different part of the program, like code, data, or stack. Each segment has a base address and a limit, defining its starting location and size in memory. When a program uses a logical address, it specifies both the segment number and an offset within that segment. The MMU or memory management software then translates this logical address into a physical address by adding the offset to the segment’s base address.

Segmentation offers several advantages, including simplified program linking and loading, and support for sharing code and data between processes. It also improves memory protection because each segment can have its own access rights. However, segmentation can lead to external fragmentation, where free memory is scattered throughout physical memory in chunks that are too small to be useful. This happens because segments can be of varying sizes, and allocating and deallocating them can create gaps in physical memory.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#define MAX_SEGMENTS 10

typedef struct {

unsigned int base;

unsigned int limit;

unsigned int protection;

} SegmentDescriptor;

typedef struct {

SegmentDescriptor* segments;

int num_segments;

} SegmentTable;

SegmentTable* initSegmentTable() {

SegmentTable* st = (SegmentTable*)malloc(sizeof(SegmentTable));

st->segments = (SegmentDescriptor*)calloc(MAX_SEGMENTS, sizeof(SegmentDescriptor));

st->num_segments = 0;

return st;

}

int addSegment(SegmentTable* st, unsigned int base, unsigned int limit, unsigned int protection) {

if(st->num_segments >= MAX_SEGMENTS) {

return -1;

}

st->segments[st->num_segments].base = base;

st->segments[st->num_segments].limit = limit;

st->segments[st->num_segments].protection = protection;

st->num_segments++;

return st->num_segments - 1;

}

6. Paging Systems

Paging is another memory management scheme that divides both logical and physical memory into fixed-size blocks called pages and frames, respectively. Similar to segmentation, a logical address in a paging system consists of a page number and an offset. The MMU uses a page table to map the page number to a frame number in physical memory, and then combines the frame number with the offset to form the physical address. Paging simplifies memory allocation because it deals with fixed-size units, reducing external fragmentation.

One of the key advantages of paging is its support for virtual memory. With paging, not all of a process’s pages need to be resident in RAM at the same time. Pages that are not currently in use can be stored on secondary storage (like a hard disk) and loaded into RAM only when needed. This allows a process to have a larger virtual address space than the available physical memory. This demand paging is managed by the operating system, which handles page faults (when a referenced page is not in RAM) and uses page replacement algorithms to determine which page to evict from RAM to make space for the newly requested page.

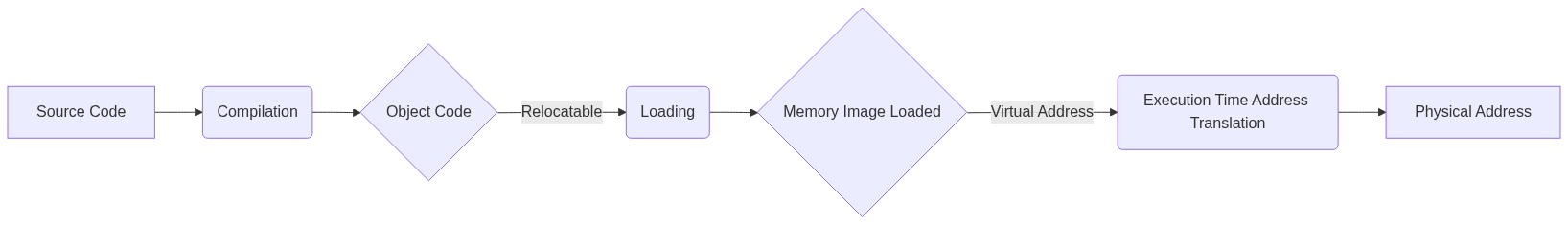

7. Address Binding

Address binding refers to the process of mapping symbolic addresses (used in program code) to physical addresses. This mapping can happen at three different stages: compile time, load time, or execution time. Compile-time binding occurs when the compiler knows the absolute memory location where the program will be loaded. This is rarely used in modern systems. Load-time binding occurs when the program is loaded into memory. The loader determines the physical addresses and modifies the relocatable addresses in the program accordingly.

Address binding occurs in three stages:

Execution-time binding, also known as dynamic address binding, is the most flexible approach. In this case, the final physical address is not determined until the instruction is actually executed. This is typically achieved through mechanisms like base and limit registers or paging and segmentation. This allows for dynamic relocation of programs in memory, supporting virtual memory and multiprogramming. Execution-time binding provides the greatest flexibility for memory management and is the prevalent method used in modern operating systems.

8. Implementation Examples

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

typedef struct {

AddressTranslator* address_translator;

SegmentTable* segment_table;

PageTable* page_table;

unsigned int translations;

unsigned int page_faults;

unsigned int segment_violations;

} MemoryManager;

MemoryManager* initMemoryManager() {

MemoryManager* mm = (MemoryManager*)malloc(sizeof(MemoryManager));

mm->address_translator = initAddressTranslator();

mm->segment_table = initSegmentTable();

mm->translations = 0;

mm->page_faults = 0;

mm->segment_violations = 0;

return mm;

}

9. Common Challenges and Solutions

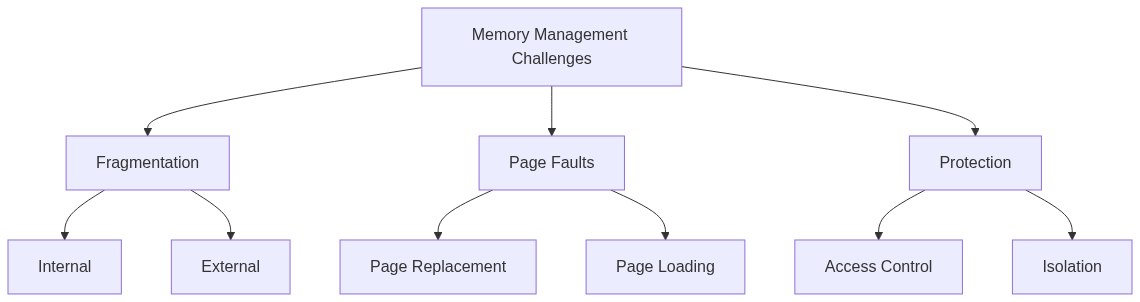

Memory management, while crucial for system efficiency and stability, presents several challenges. A primary challenge is fragmentation, which occurs when free memory is scattered in small, non-contiguous blocks, making it difficult to allocate memory to new processes or expand existing ones. Fragmentation comes in two forms: internal fragmentation, where allocated memory blocks are larger than required, wasting space within the block; and external fragmentation, where enough total free memory exists, but it is divided into small, unusable chunks. Solutions for fragmentation include compaction, which involves rearranging allocated memory blocks to create larger contiguous free spaces, and paging/segmentation, which reduces external fragmentation by using fixed-size blocks.

Another significant challenge is handling page faults, which occur when a process accesses a page that is not currently present in RAM. This necessitates retrieving the page from secondary storage, which is a relatively slow operation. Minimizing page faults is essential for performance. Techniques such as page replacement algorithms (e.g., LRU, FIFO) determine which page to evict from RAM to make room for the requested page. Other strategies include prefetching, where pages likely to be accessed soon are loaded into RAM in advance, and working set management, which keeps the most frequently used pages in memory. Memory protection is yet another challenge, requiring mechanisms to prevent processes from accessing memory outside their allocated regions or violating access permissions (read, write, execute). Solutions include hardware-based protection through the MMU and software-based access control mechanisms enforced by the operating system.

10. Performance Considerations

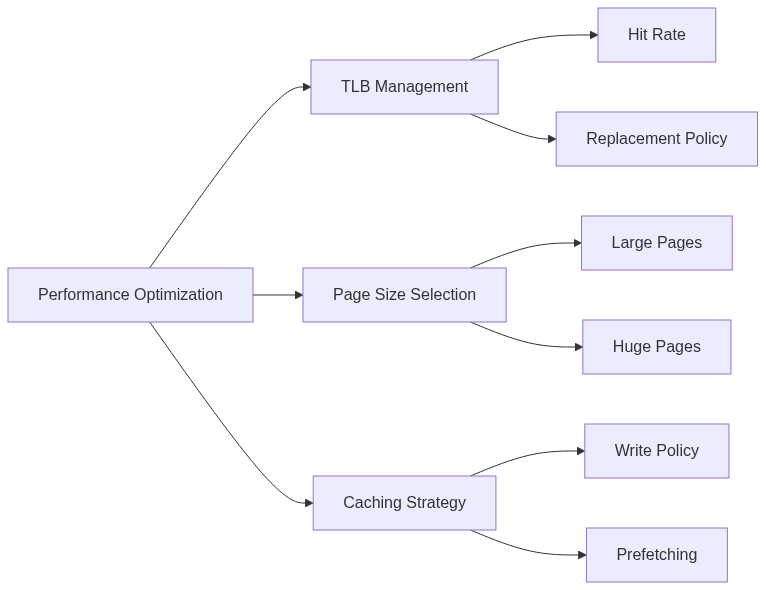

Optimizing memory management for performance is crucial in modern systems. One key area is efficient TLB management. The Translation Lookaside Buffer (TLB) is a small, fast cache that stores recent virtual-to-physical address translations. A high TLB hit rate (the percentage of memory accesses that find the translation in the TLB) significantly speeds up address translation. Strategies for improving TLB hit rate include increasing the TLB size and using smart TLB replacement policies.

Another performance factor is page size selection. Larger page sizes can reduce the overhead of page table lookups and improve TLB hit rates. However, larger pages can also increase internal fragmentation and waste memory if a process doesn’t use the entire page. Systems often support multiple page sizes, allowing for flexibility in managing different types of memory regions. Caching strategies also play a significant role. Efficient caching policies, such as write-back and write-through, can minimize the number of expensive write operations to main memory. Prefetching, discussed earlier, can also significantly improve performance by anticipating future memory accesses and loading data into the cache before it is needed. Careful tuning of these parameters, considering the specific workload and system characteristics, is crucial for maximizing memory performance.

11. Best Practices

- Use appropriate page sizes for different memory regions.

- Implement efficient TLB management.

- Monitor and optimize page fault rates.

- Implement proper memory protection mechanisms.

- Use memory alignment for better performance.

12. Conclusion and Future Trends

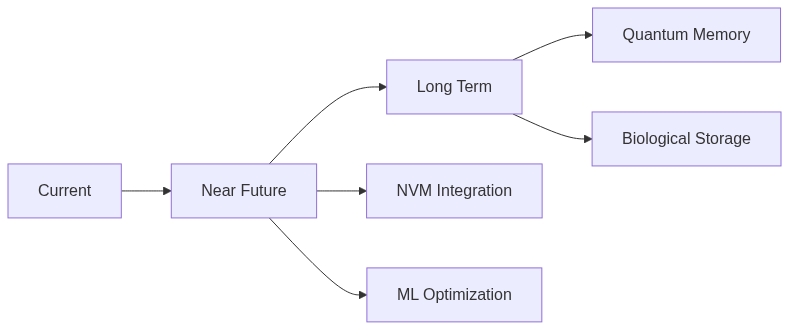

The future of memory management is moving towards:

- Heterogeneous memory architectures

- Non-volatile memory integration

- Machine learning-based prediction

- Advanced security features

Thanks, Will Meet in Chapter 17