Day 17: Contiguous Memory Allocation

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Memory Allocation Strategies

- Memory Partitioning

- Memory Compaction

- Memory Protection

- Implementation Examples

- Performance Analysis

- Best Practices

- Conclusion

1. Introduction

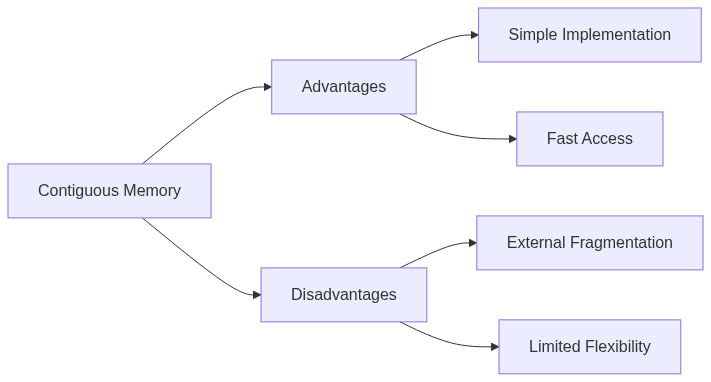

Contiguous memory allocation is a fundamental memory management technique where each process is allocated a single continuous block of memory. This approach, while simple, presents both advantages and challenges in modern operating systems. Its simplicity makes it easy to implement and manage, especially in systems with limited resources. However, as memory requests become more dynamic and varied in size, the limitations of contiguous allocation become more apparent.

Contiguous memory allocation offers fast access to memory due to the linear addressing scheme. Since the entire block of memory assigned to a process is contiguous, accessing different parts of the allocated memory is straightforward and efficient. This is particularly beneficial for applications that require predictable memory access patterns. However, this simplicity comes at the cost of potential fragmentation and difficulty in handling varying memory requests.

2. Memory Allocation Strategies

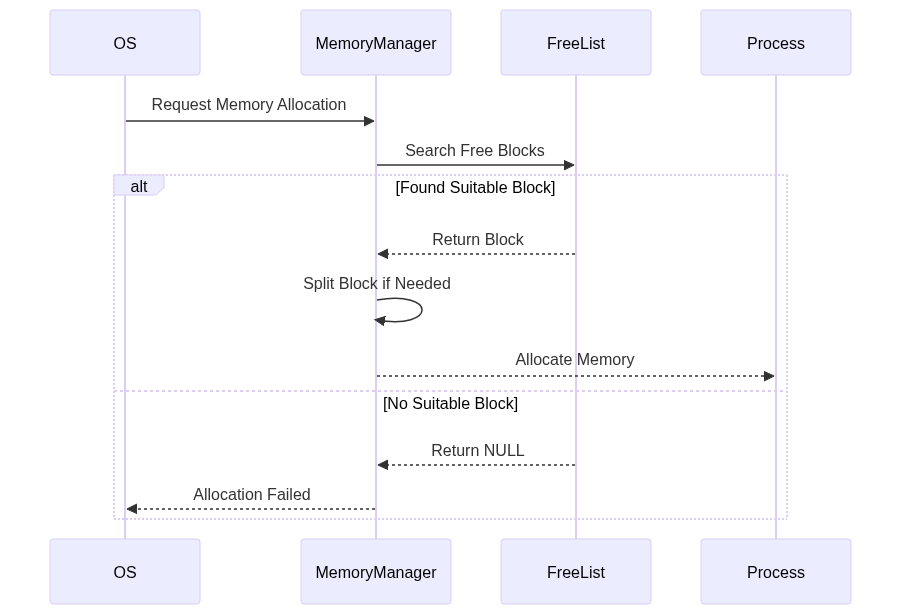

This section explores different strategies for allocating contiguous memory blocks, including First Fit, Best Fit, and Worst Fit. These strategies dictate how the operating system chooses a free block of memory to satisfy a process’s memory request. The choice of strategy impacts the efficiency of memory utilization and the degree of fragmentation.

The provided C code implements these strategies, demonstrating how they can be integrated into a memory management system. The code provides functions for initializing the memory manager, allocating memory based on the chosen strategy, and managing free and allocated memory blocks. Each strategy has its trade-offs in terms of speed and memory utilization.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <stdbool.h>

#define MAX_MEMORY_SIZE 1024

#define MIN_PARTITION_SIZE 64

typedef struct MemoryBlock {

size_t size;

size_t start_address;

bool is_allocated;

struct MemoryBlock* next;

} MemoryBlock;

typedef struct {

MemoryBlock* head;

size_t total_size;

size_t free_size;

int allocation_strategy; // 1: First Fit, 2: Best Fit, 3: Worst Fit

} MemoryManager;

MemoryManager* initMemoryManager(size_t size, int strategy) {

MemoryManager* manager = (MemoryManager*)malloc(sizeof(MemoryManager));

manager->total_size = size;

manager->free_size = size;

manager->allocation_strategy = strategy;

// Create initial free block

manager->head = (MemoryBlock*)malloc(sizeof(MemoryBlock));

manager->head->size = size;

manager->head->start_address = 0;

manager->head->is_allocated = false;

manager->head->next = NULL;

return manager;

}

// First Fit Algorithm

MemoryBlock* firstFit(MemoryManager* manager, size_t size) {

MemoryBlock* current = manager->head;

while(current != NULL) {

if(!current->is_allocated && current->size >= size) {

return current;

}

current = current->next;

}

return NULL;

}

// Best Fit Algorithm

MemoryBlock* bestFit(MemoryManager* manager, size_t size) {

MemoryBlock* current = manager->head;

MemoryBlock* best_block = NULL;

size_t smallest_difference = manager->total_size;

while(current != NULL) {

if(!current->is_allocated && current->size >= size) {

size_t difference = current->size - size;

if(difference < smallest_difference) {

smallest_difference = difference;

best_block = current;

}

}

current = current->next;

}

return best_block;

}

// Worst Fit Algorithm

MemoryBlock* worstFit(MemoryManager* manager, size_t size) {

MemoryBlock* current = manager->head;

MemoryBlock* worst_block = NULL;

size_t largest_difference = 0;

while(current != NULL) {

if(!current->is_allocated && current->size >= size) {

size_t difference = current->size - size;

if(difference > largest_difference) {

largest_difference = difference;

worst_block = current;

}

}

current = current->next;

}

return worst_block;

}

void* allocateMemory(MemoryManager* manager, size_t size) {

if(size < MIN_PARTITION_SIZE || size > manager->free_size) {

return NULL;

}

MemoryBlock* selected_block = NULL;

switch(manager->allocation_strategy) {

case 1:

selected_block = firstFit(manager, size);

break;

case 2:

selected_block = bestFit(manager, size);

break;

case 3:

selected_block = worstFit(manager, size);

break;

default:

return NULL;

}

if(selected_block == NULL) {

return NULL;

}

if(selected_block->size > size + MIN_PARTITION_SIZE) {

MemoryBlock* new_block = (MemoryBlock*)malloc(sizeof(MemoryBlock));

new_block->size = selected_block->size - size;

new_block->start_address = selected_block->start_address + size;

new_block->is_allocated = false;

new_block->next = selected_block->next;

selected_block->size = size;

selected_block->next = new_block;

}

selected_block->is_allocated = true;

manager->free_size -= selected_block->size;

return (void*)selected_block->start_address;

}

3. Memory Partitioning

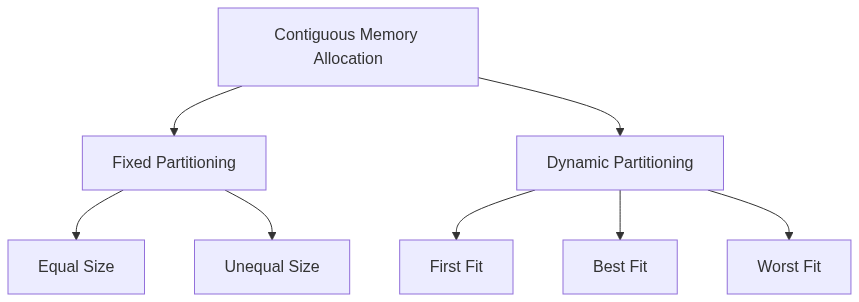

Memory partitioning is the process of dividing the available memory into smaller regions or partitions to accommodate multiple processes. This can be done using fixed-size partitions or dynamic partitions, where partition sizes adjust based on the memory requests. The partitioning scheme significantly influences how efficiently memory is used and the level of fragmentation.

Dynamic partitioning allows for more flexible memory allocation by creating partitions based on the specific needs of processes. This reduces internal fragmentation but can lead to external fragmentation as free blocks become scattered throughout memory. Effective management of free blocks becomes crucial in dynamic partitioning schemes.

4. Memory Compaction

Memory compaction is a technique used to address external fragmentation by relocating allocated memory blocks to create a larger contiguous free space. This process involves moving the contents of memory and updating the corresponding addresses, which can be a time-consuming operation. However, it can significantly improve memory utilization and allow for the allocation of larger contiguous blocks.

Compaction becomes necessary when external fragmentation reaches a point where it hinders the allocation of new processes. The provided code demonstrates a basic compaction algorithm that merges adjacent free blocks and shuffles allocated blocks to create a larger contiguous free area. This helps in reclaiming fragmented memory and improving the overall efficiency of the memory management system.

void compactMemory(MemoryManager* manager) {

if(manager->head == NULL) return;

MemoryBlock* current = manager->head;

size_t new_address = 0;

while(current != NULL) {

if(current->is_allocated) {

// Move block to new address

current->start_address = new_address;

new_address += current->size;

}

current = current->next;

}

// Merge free blocks

current = manager->head;

while(current != NULL && current->next != NULL) {

if(!current->is_allocated && !current->next->is_allocated) {

// Merge blocks

current->size += current->next->size;

MemoryBlock* temp = current->next;

current->next = temp->next;

free(temp);

} else {

current = current->next;

}

}

}

5. Memory Protection

Memory protection mechanisms ensure that processes can only access the memory regions allocated to them, preventing unauthorized access and maintaining system stability. This is crucial for preventing processes from interfering with each other and protecting critical system data. Various techniques, such as base and limit registers and access control lists, are used to enforce memory protection.

Memory protection is implemented using hardware and software mechanisms that control access to memory locations. Base and limit registers define the boundaries of a process’s allocated memory, while access rights specify the type of operations (read, write, execute) allowed within those boundaries. This prevents processes from accessing memory outside their designated areas, enhancing system security and stability.

6. Basic Implementation

The code demonstrates how to manage memory regions with different access permissions and how to enforce these permissions during memory access.

The ProtectedMemoryManager struct integrates the memory management functions with a protection table that stores the access rights for each memory region. This example illustrates how a more robust and secure memory management system can be built upon the principles of contiguous allocation.

typedef struct {

size_t base_address;

size_t limit;

int protection_bits; // 1: read, 2: write, 4: execute

} MemoryProtection;

typedef struct {

MemoryManager* memory_manager;

MemoryProtection* protection_table;

int num_regions;

} ProtectedMemoryManager;

ProtectedMemoryManager* initProtectedMemoryManager(size_t size, int strategy) {

ProtectedMemoryManager* pmm = (ProtectedMemoryManager*)malloc(

sizeof(ProtectedMemoryManager)

);

pmm->memory_manager = initMemoryManager(size, strategy);

pmm->protection_table = (MemoryProtection*)malloc(

sizeof(MemoryProtection) * 100

);

pmm->num_regions = 0;

return pmm;

}

bool checkMemoryAccess(ProtectedMemoryManager* pmm,

size_t address,

int access_type) {

for(int i = 0; i < pmm->num_regions; i++) {

MemoryProtection* mp = &pmm->protection_table[i];

if(address >= mp->base_address &&

address < mp->base_address + mp->limit) {

return (mp->protection_bits & access_type) != 0;

}

}

return false;

}

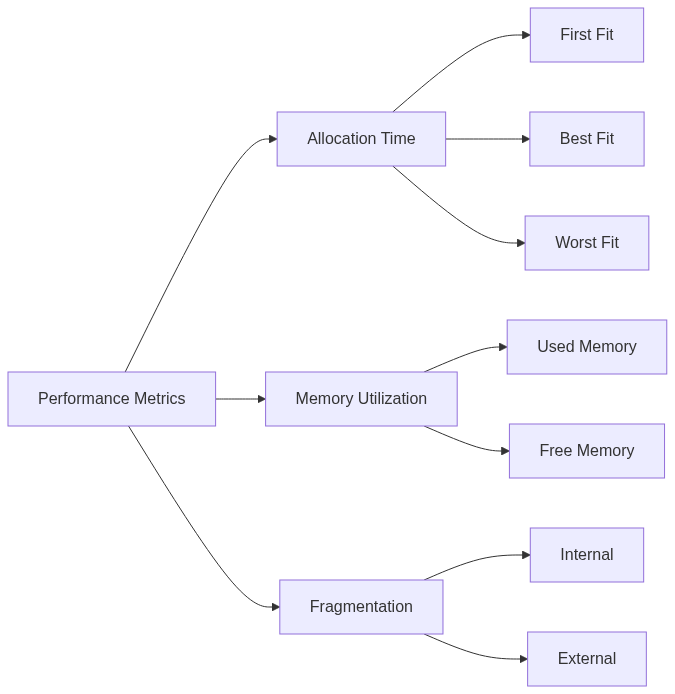

7. Performance Analysis

Analyzing the performance of different memory allocation strategies is essential for choosing the most suitable approach for a given workload. Metrics like allocation time, memory utilization, and fragmentation provide insights into the efficiency of each strategy. Understanding these metrics helps optimize memory management for specific application requirements.

Different workloads and memory access patterns benefit from different allocation strategies. Analyzing performance characteristics like allocation time, memory utilization, and fragmentation allows for informed decisions about which strategy best suits the specific requirements of a system.

8. Best Practices

- Choose appropriate allocation strategy based on workload: Consider factors like request size distribution and frequency to select the most efficient strategy.

- Implement regular memory compaction: Periodic compaction reduces external fragmentation and improves memory utilization.

- Monitor fragmentation levels: Tracking fragmentation helps identify potential issues and trigger compaction when necessary.

- Use protection mechanisms: Employ base/limit registers and access control lists to ensure memory security.

- Optimize block sizes: Choosing appropriate minimum block sizes can minimize internal fragmentation.

9. Conclusion

Contiguous memory allocation, despite its limitations, remains relevant in specific use cases. Its simplicity and speed make it suitable for certain embedded systems or real-time applications with predictable memory requirements. However, its susceptibility to fragmentation makes it less suitable for dynamic environments. Modern systems often combine contiguous allocation with other techniques like paging or segmentation for more efficient and flexible memory management.

While contiguous allocation offers simplicity and fast access, its limitations regarding fragmentation make it less suitable for modern general-purpose operating systems. Its principles, however, continue to be relevant in specialized systems and as a foundation for understanding more complex memory management techniques.