Day 20: Page Replacement Algorithms - A Deep Dive

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Understanding Page Faults

- Page Replacement Algorithms

- Performance Analysis

- Real-world Applications

- Performance Metrics

- Conclusion

- References and Further Reading

1. Introduction

Page replacement algorithms are crucial components of virtual memory management. They determine which page to evict from physical memory when a page fault occurs and a new page needs to be loaded. The primary goal of these algorithms is to minimize the number of page faults, which directly impacts system performance. Different algorithms employ various strategies to predict which pages are least likely to be used in the future.

Effective page replacement algorithms strive to balance complexity with performance. While some algorithms are simple to implement, they may not always provide optimal page fault reduction. More sophisticated algorithms can offer better performance but might introduce higher overhead.

2. Understanding Page Faults

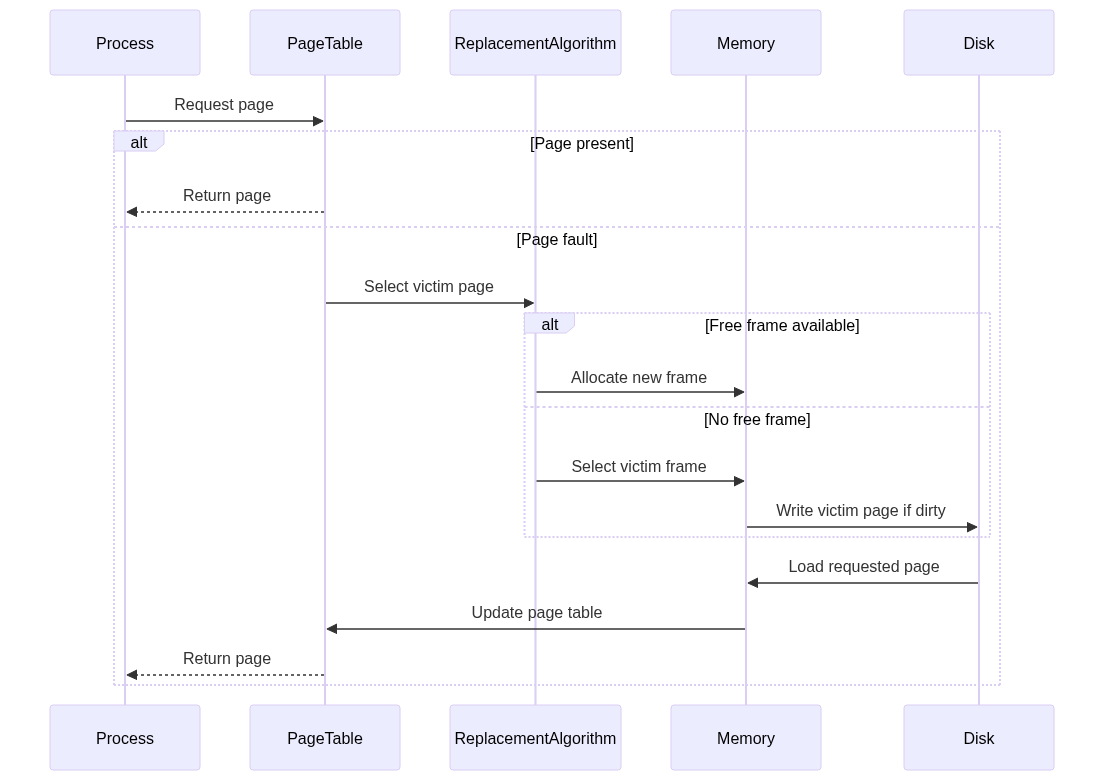

A page fault occurs when a process attempts to access a page that is present in its virtual address space but not currently loaded in physical memory. This triggers a trap to the operating system, which must then load the required page from secondary storage. Understanding the different types of page faults is essential for designing and implementing effective page replacement algorithms.

There are different types of page faults, each with varying implications for system performance. Minor page faults are relatively quick to resolve, often involving only updates to page tables. Major page faults, on the other hand, require disk I/O, resulting in significant delays. Invalid page faults indicate memory access violations and typically lead to program termination.

- Minor Page Fault: Occurs when the page is present in memory but not marked as accessible by the Memory Management Unit (MMU). Resolution is quick and involves updating the page table entries.

- Major Page Fault: Occurs when the page needs to be loaded from disk. This is significantly slower, requiring I/O operations.

- Invalid Page Fault: Occurs when a process attempts to access memory that is not part of its virtual address space. This typically results in a segmentation fault and program termination.

3. Page Replacement Algorithms

3.1 FIFO (First-In-First-Out)

The FIFO algorithm replaces the oldest page in memory. This is simple to implement using a queue data structure. While easy to understand and implement, FIFO can suffer from Belady’s Anomaly, where increasing the number of page frames can sometimes lead to an increase in page faults.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <stdbool.h>

typedef struct {

int *frames;

int capacity;

int size;

int head;

} FIFOQueue;

FIFOQueue* createFIFOQueue(int capacity) {

FIFOQueue* queue = (FIFOQueue*)malloc(sizeof(FIFOQueue));

queue->frames = (int*)malloc(capacity * sizeof(int));

queue->capacity = capacity;

queue->size = 0;

queue->head = 0;

return queue;

}

bool isPagePresent(FIFOQueue* queue, int page) {

for(int i = 0; i < queue->size; i++) {

if(queue->frames[i] == page)

return true;

}

return false;

}

void fifoPageReplacement(int pages[], int n, int capacity) {

FIFOQueue* queue = createFIFOQueue(capacity);

int page_faults = 0;

for(int i = 0; i < n; i++) {

if(!isPagePresent(queue, pages[i])) {

page_faults++;

if(queue->size < queue->capacity) {

queue->frames[queue->size++] = pages[i];

} else {

queue->frames[queue->head] = pages[i];

queue->head = (queue->head + 1) % queue->capacity;

}

printf("Page fault occurred for page %d\n", pages[i]);

}

}

printf("Total page faults: %d\n", page_faults);

free(queue->frames);

free(queue);

}

3.2 LRU (Least Recently Used)

The LRU algorithm replaces the page that has not been used for the longest time. This is based on the principle of locality of reference, assuming that recently used pages are more likely to be used again in the near future. While LRU generally performs well, it can be more complex to implement efficiently.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <limits.h>

typedef struct {

int page;

int last_used;

} PageFrame;

void lruPageReplacement(int pages[], int n, int capacity) {

PageFrame* frames = (PageFrame*)malloc(capacity * sizeof(PageFrame));

int page_faults = 0;

int current_size = 0;

for(int i = 0; i < capacity; i++) {

frames[i].page = -1;

frames[i].last_used = -1;

}

for(int i = 0; i < n; i++) {

int page = pages[i];

bool page_found = false;

// Check if page already exists

for(int j = 0; j < current_size; j++) {

if(frames[j].page == page) {

frames[j].last_used = i;

page_found = true;

break;

}

}

if(!page_found) {

page_faults++;

if(current_size < capacity) {

frames[current_size].page = page;

frames[current_size].last_used = i;

current_size++;

} else {

// Find least recently used page

int lru_index = 0;

int min_last_used = INT_MAX;

for(int j = 0; j < capacity; j++) {

if(frames[j].last_used < min_last_used) {

min_last_used = frames[j].last_used;

lru_index = j;

}

}

frames[lru_index].page = page;

frames[lru_index].last_used = i;

}

printf("Page fault occurred for page %d\n", page);

}

}

printf("Total page faults: %d\n", page_faults);

free(frames);

}

3.3 Optimal Algorithm

The Optimal algorithm replaces the page that will not be used for the longest time in the future. This provides the theoretically optimal performance but is not practical in real-world systems as it requires knowledge of future memory access patterns. It serves as a benchmark for evaluating other algorithms.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <limits.h>

int findFarthest(int pages[], int n, int current_index, int* frames, int capacity) {

int farthest = -1;

int farthest_index = -1;

for(int i = 0; i < capacity; i++) {

int j;

for(j = current_index; j < n; j++) {

if(frames[i] == pages[j]) {

if(j > farthest) {

farthest = j;

farthest_index = i;

}

break;

}

}

if(j == n) return i; // Page not referenced in future

}

return (farthest_index == -1) ? 0 : farthest_index;

}

void optimalPageReplacement(int pages[], int n, int capacity) {

int* frames = (int*)malloc(capacity * sizeof(int));

int page_faults = 0;

int current_size = 0;

for(int i = 0; i < capacity; i++)

frames[i] = -1;

for(int i = 0; i < n; i++) {

bool page_found = false;

for(int j = 0; j < current_size; j++) {

if(frames[j] == pages[i]) {

page_found = true;

break;

}

}

if(!page_found) {

page_faults++;

if(current_size < capacity) {

frames[current_size++] = pages[i];

} else {

int replace_index = findFarthest(pages, n, i + 1, frames, capacity);

frames[replace_index] = pages[i];

}

printf("Page fault occurred for page %d\n", pages[i]);

}

}

printf("Total page faults: %d\n", page_faults);

free(frames);

}

4. Performance Analysis

Comparing the performance of different page replacement algorithms requires running them with representative workloads and measuring metrics such as the number of page faults. The provided example demonstrates a basic comparison using a sample page access sequence. More comprehensive analysis would involve more extensive testing and statistical analysis.

int main() {

int pages[] = {7, 0, 1, 2, 0, 3, 0, 4, 2, 3, 0, 3, 2};

int n = sizeof(pages)/sizeof(pages[0]);

int capacity = 4;

printf("FIFO Algorithm:\n");

fifoPageReplacement(pages, n, capacity);

printf("\nLRU Algorithm:\n");

lruPageReplacement(pages, n, capacity);

printf("\nOptimal Algorithm:\n");

optimalPageReplacement(pages, n, capacity);

return 0;

}

5. Real-world Applications

Operating systems like Linux and Windows employ variations of these algorithms, often incorporating optimizations and adaptations to suit specific hardware and workload characteristics. Understanding these real-world implementations provides valuable insights into the practical application of page replacement algorithms.

- Linux: Uses a modified version of LRU called the Clock algorithm, along with page frame reclaiming and multiple LRU lists.

- Windows: Uses a modified Clock algorithm, working set trimming, and priority-based page replacement.

6. Performance Metrics

- Page Fault Rate: Number of page faults per memory access. A lower rate is better.

- Memory Utilization: Percentage of memory frames in use. Higher utilization is generally desirable.

- Response Time: Time taken to handle a page fault. This is crucial for interactive applications.

7. Conclusion

Each page replacement algorithm has its strengths and weaknesses. FIFO is simple but can be inefficient. LRU performs well but can be complex. The Optimal algorithm is a theoretical ideal. Real-world systems often use hybrid approaches or approximations to balance performance and complexity. Choosing the right algorithm depends on the specific workload and system requirements.

8. References and Further Reading

- “The Evolution of the Unix Time-sharing System” by Dennis M. Ritchie

- “Page Replacement in Linux 2.4 Memory Management” by Rik van Riel