Day 35: Inter-Process Communication (IPC)

Table of Contents

- Introduction to IPC

- Types of IPC Mechanisms

- Pipes in Detail

- Message Queues

- Advanced IPC Concepts

- Error Handling

- Performance Considerations

- Security Aspects

- Conclusion

1. Introduction to IPC

Inter-Process Communication (IPC) is a set of mechanisms that allow processes to communicate and synchronize their actions. IPC is fundamental to modern operating systems and distributed computing. It enables processes to share data, coordinate tasks, and manage resources efficiently.

Key Concepts:

- Process Isolation: Processes have separate memory spaces and cannot directly access each other’s memory. IPC provides a controlled way for processes to share data without violating this isolation.

- Data Exchange: IPC mechanisms allow processes to exchange data in a structured manner, ensuring that information is passed securely and efficiently.

- Synchronization: Processes often need to coordinate their actions, especially in multi-threaded or distributed systems. IPC provides synchronization mechanisms to ensure that processes work together harmoniously.

- Resource Sharing: IPC allows multiple processes to share system resources, such as files, memory, or network connections, in a controlled and efficient manner.

2. Types of IPC Mechanisms

2.1 Pipes

Pipes are one of the simplest forms of IPC, providing a unidirectional communication channel between related processes (typically parent and child processes). Data flows in a First-In-First-Out (FIFO) manner, making pipes ideal for stream-based data transfer.

- Unidirectional Communication: Pipes allow data to flow in one direction only, from the writer to the reader.

- FIFO Data Flow: Data is read in the same order it is written, ensuring consistency.

- Related Processes: Pipes are typically used between processes that have a parent-child relationship.

- Stream-Based Data Transfer: Pipes are well-suited for continuous data streams, such as logging or real-time data processing.

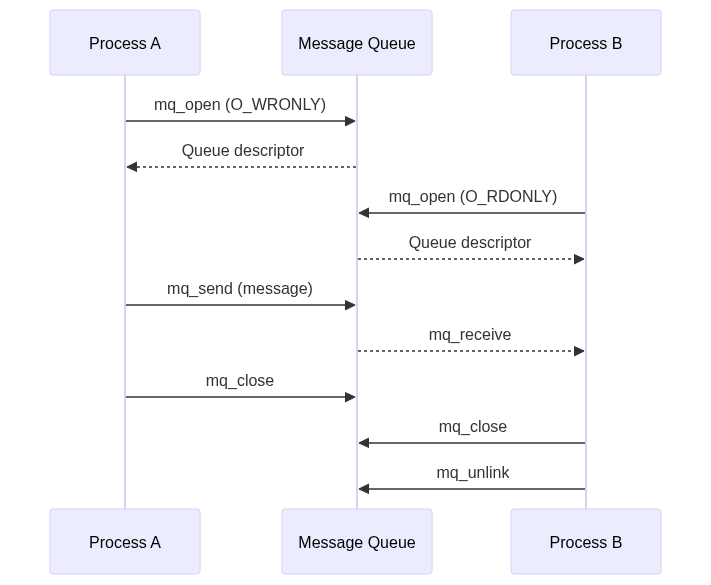

2.2 Message Queues

Message queues provide a more flexible form of IPC, allowing bidirectional communication between processes. Messages are stored in a queue and can be retrieved in order of priority, making message queues ideal for complex communication patterns.

- Bidirectional Communication: Unlike pipes, message queues allow both sending and receiving of messages.

- Message-Based Data Transfer: Data is transferred in discrete messages, which can include metadata such as priority levels.

- Priority Support: Messages can be assigned different priority levels, allowing high-priority messages to be processed first.

- System-Wide Accessibility: Message queues can be accessed by any process with the appropriate permissions, making them suitable for inter-process communication across the system.

3. Pipes in Detail

3.1 Anonymous Pipes Implementation

The following code demonstrates how to create and use an anonymous pipe for communication between a parent and child process.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <sys/wait.h>

#define BUFFER_SIZE 256

int main() {

int pipe_fd[2];

pid_t pid;

char buffer[BUFFER_SIZE];

if (pipe(pipe_fd) == -1) {

perror("pipe");

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

pid = fork();

if (pid == -1) {

perror("fork");

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

if (pid == 0) { // Child process

close(pipe_fd[1]); // Close write end

// Read from pipe

ssize_t bytes_read = read(pipe_fd[0], buffer, BUFFER_SIZE);

if (bytes_read > 0) {

printf("Child received: %s\n", buffer);

}

close(pipe_fd[0]);

exit(EXIT_SUCCESS);

} else { // Parent process

close(pipe_fd[0]); // Close read end

const char *message = "Hello from parent!";

write(pipe_fd[1], message, strlen(message) + 1);

close(pipe_fd[1]);

wait(NULL); // Wait for child to finish

}

return 0;

}

Steps to Run the Code:

- Compile the Code: Save the code in a file named

pipe_example.cand compile it using a C compiler, such asgcc:gcc -o pipe_example pipe_example.c - Run the Executable: Execute the compiled program:

./pipe_example - Expected Output: The child process will receive the message sent by the parent process and print it to the console:

Child received: Hello from parent!

3.2 Named Pipes (FIFOs)

Named pipes, also known as FIFOs, allow communication between unrelated processes. The following code demonstrates how to create and use a named pipe.

Writer Process:

// fifo_writer.c

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <fcntl.h>

#include <sys/stat.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <string.h>

#define FIFO_PATH "/tmp/myfifo"

int main() {

mkfifo(FIFO_PATH, 0666);

printf("Opening FIFO for writing...\n");

int fd = open(FIFO_PATH, O_WRONLY);

const char *message = "Message through FIFO";

write(fd, message, strlen(message) + 1);

close(fd);

return 0;

}

Reader Process:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <fcntl.h>

#include <sys/stat.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

#define FIFO_PATH "/tmp/myfifo"

#define BUFFER_SIZE 256

int main() {

char buffer[BUFFER_SIZE];

printf("Opening FIFO for reading...\n");

int fd = open(FIFO_PATH, O_RDONLY);

read(fd, buffer, BUFFER_SIZE);

printf("Received: %s\n", buffer);

close(fd);

unlink(FIFO_PATH);

return 0;

}

Steps to Run the Code:

- Compile the Code: Save the writer and reader code in separate files (

fifo_writer.candfifo_reader.c) and compile them:gcc -o fifo_writer fifo_writer.c gcc -o fifo_reader fifo_reader.c - Run the Writer: Start the writer process:

./fifo_writer - Run the Reader: In a separate terminal, start the reader process:

./fifo_reader - Expected Output: The reader process will receive the message sent by the writer process and print it to the console:

Received: Message through FIFO

4. Message Queues

4.1 POSIX Message Queue Implementation

The following code demonstrates how to create and use a POSIX message queue for communication between processes.

Sender Process:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <mqueue.h>

#include <sys/stat.h>

#include <fcntl.h>

#define QUEUE_NAME "/test_queue"

#define MAX_MSG_SIZE 256

#define MSG_PRIO 1

int main() {

mqd_t mq;

struct mq_attr attr;

// Set queue attributes

attr.mq_flags = 0;

attr.mq_maxmsg = 10;

attr.mq_msgsize = MAX_MSG_SIZE;

attr.mq_curmsgs = 0;

mq = mq_open(QUEUE_NAME, O_CREAT | O_WRONLY, 0644, &attr);

if (mq == (mqd_t)-1) {

perror("mq_open");

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

const char *message = "Test message";

if (mq_send(mq, message, strlen(message) + 1, MSG_PRIO) == -1) {

perror("mq_send");

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

mq_close(mq);

return 0;

}

Receiver Process:

// mqueue_receiver.c

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <mqueue.h>

#include <sys/stat.h>

#include <fcntl.h>

#define QUEUE_NAME "/test_queue"

#define MAX_MSG_SIZE 256

int main() {

mqd_t mq;

char buffer[MAX_MSG_SIZE];

unsigned int prio;

mq = mq_open(QUEUE_NAME, O_RDONLY);

if (mq == (mqd_t)-1) {

perror("mq_open");

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

ssize_t bytes_read = mq_receive(mq, buffer, MAX_MSG_SIZE, &prio);

if (bytes_read == -1) {

perror("mq_receive");

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

printf("Received message: %s (priority: %u)\n", buffer, prio);

mq_close(mq);

mq_unlink(QUEUE_NAME);

return 0;

}

Steps to Run the Code:

- Compile the Code: Save the sender and receiver code in separate files (

mqueue_sender.candmqueue_receiver.c) and compile them:gcc -o mqueue_sender mqueue_sender.c -lrt gcc -o mqueue_receiver mqueue_receiver.c -lrt - Run the Sender: Start the sender process:

./mqueue_sender - Run the Receiver: In a separate terminal, start the receiver process:

./mqueue_receiver - Expected Output: The receiver process will receive the message sent by the sender process and print it to the console along with its priority:

Received message: Test message (priority: 1)

5. Advanced IPC Concepts

5.1 Message Queue Attributes

Message queues have several attributes that can be configured to control their behavior. These attributes include the maximum number of messages, the maximum message size, and the current number of messages in the queue.

struct mq_attr {

long mq_flags; /* Message queue flags */

long mq_maxmsg; /* Maximum number of messages */

long mq_msgsize; /* Maximum message size */

long mq_curmsgs; /* Number of messages currently queued */

};

5.2 Non-blocking Operations

Message queues can be configured to operate in non-blocking mode, allowing processes to continue execution even if no messages are available.

mqd_t mq = mq_open(QUEUE_NAME, O_RDONLY | O_NONBLOCK);

6. Error Handling

Proper error handling is essential when working with IPC mechanisms. The following code demonstrates a common error handling pattern.

#include <errno.h>

void handle_error(const char *msg) {

perror(msg);

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

if (mq_send(mq, message, strlen(message) + 1, prio) == -1) {

handle_error("mq_send");

}

7. Performance Considerations

- Message Size: Larger messages increase overhead and may impact performance.

- Queue Length: Longer queues consume more system resources and may lead to delays.

- Blocking vs Non-blocking: Blocking operations can impact system responsiveness, while non-blocking operations allow for more efficient resource utilization.

- Priority Handling: Higher priority messages are processed first, which can affect the overall performance of the system.

8. Security Aspects

- Access Control: Use appropriate permissions for message queues to prevent unauthorized access.

- Resource Limits: Set proper limits for queue size and message count to prevent resource exhaustion.

- Cleanup: Always remove message queues when they are no longer needed to free up system resources.

- Validation: Verify message integrity and sender authenticity to prevent security breaches.

9. Conclusion

IPC mechanisms, particularly pipes and message queues, are essential tools for inter-process communication in Unix-like systems. Understanding these mechanisms and their proper implementation is crucial for developing robust and efficient multi-process applications.