Day-39: Real-Time Operating Systems Internals

Table of Contents

- Introduction to RTOS

- RTOS Kernel Architecture

- Task Management and Scheduling

- Interrupt Handling in RTOS

- Timer Management

- Inter-Task Communication

- Memory Management in RTOS

- Performance Considerations

- Conclusion

1. Introduction to RTOS

A Real-Time Operating System (RTOS) is a specialized operating system designed to handle real-time applications that require precise timing and high reliability. Unlike general-purpose operating systems, RTOS ensures deterministic behavior, meaning it guarantees that tasks will complete within a specified time frame. This is critical for applications like automotive systems, medical devices, and industrial automation, where delays can lead to catastrophic outcomes.

Key Characteristics of RTOS

- Deterministic Behavior: RTOS guarantees predictable response times for system calls and interrupts. For example, in an automotive system, the airbag deployment must occur within milliseconds of impact detection.

- Priority-Based Scheduling: Tasks are assigned priorities, and the scheduler ensures that the highest-priority task always gets CPU time. In a medical ventilator, air pressure monitoring must take precedence over display updates.

- Minimal Interrupt Latency: RTOS minimizes the time between an interrupt occurrence and its service routine execution. In industrial automation, an emergency stop signal must be processed immediately to prevent equipment damage.

- Preemptive Multitasking: Higher-priority tasks can interrupt lower-priority ones immediately, ensuring critical operations are never delayed.

2. RTOS Kernel Architecture

The RTOS kernel is the core component that manages system resources and provides services to applications. It consists of several key components:

- Scheduler: Implements the task scheduling algorithm and maintains task states.

- Task Manager: Handles task creation, deletion, and state transitions.

- Interrupt Handler: Manages hardware and software interrupts with minimal latency.

- Timer Services: Provides high-resolution timing services for tasks and system operations.

Task Control Block (TCB) Implementation

The TCB is a data structure that holds task-specific information. Below is a basic implementation of a TCB in C:

typedef struct {

uint32_t *stack_ptr; // Current stack pointer

uint32_t stack_size; // Stack size

uint8_t priority; // Task priority

TaskState_t state; // Current task state

void (*task_function)(void*); // Task function pointer

void *task_parameters; // Task parameters

uint32_t time_slice; // Time slice for round-robin

char task_name[16]; // Task identifier

} TCB_t;

- Stack Pointer: Points to the current stack location of the task.

- Priority: Determines the task’s execution priority.

- Task Function: The function that the task will execute.

- Task Parameters: Parameters passed to the task function.

- Time Slice: The time allocated for the task in a round-robin scheduling scheme.

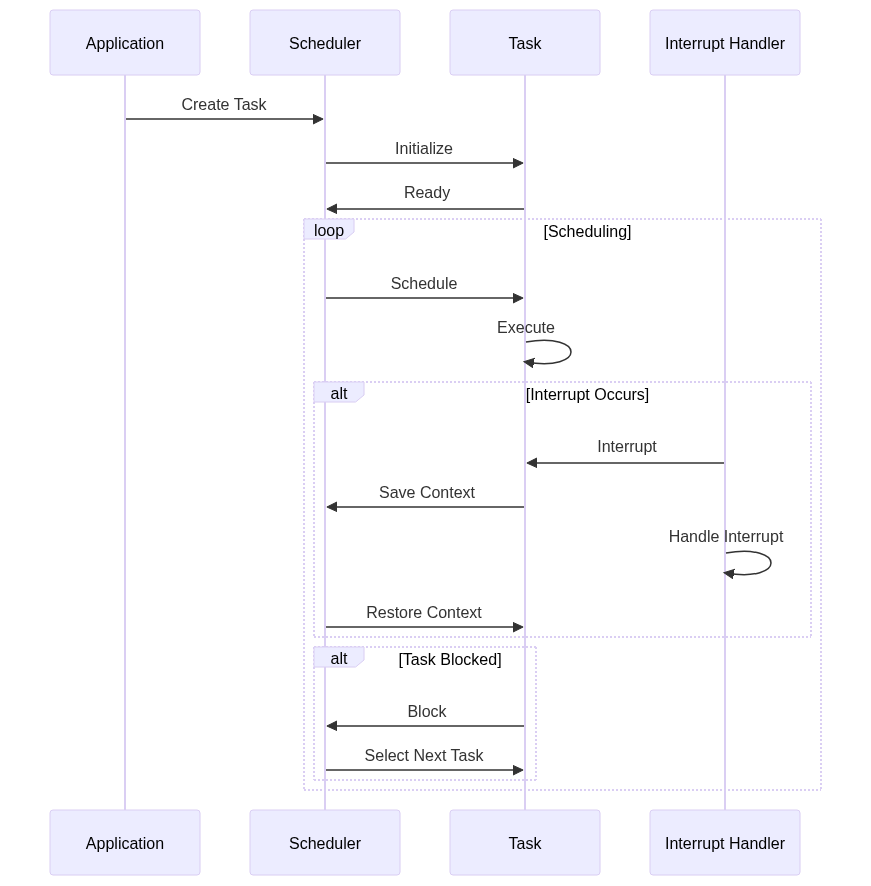

3. Task Management and Scheduling

Task management in RTOS involves creating, scheduling, and maintaining tasks throughout their lifecycle. Tasks can be in one of the following states:

- Running: Currently executing on the CPU.

- Ready: Ready to execute but waiting for CPU.

- Blocked: Waiting for an event or resource.

- Suspended: Temporarily inactive.

- Terminated: Completed execution.

Task Creation Implementation

Below is an example of how to create a task in an RTOS:

typedef enum {

TASK_RUNNING,

TASK_READY,

TASK_BLOCKED,

TASK_SUSPENDED,

TASK_TERMINATED

} TaskState_t;

TCB_t* create_task(void (*task_func)(void*),

void* parameters,

uint8_t priority,

uint32_t stack_size) {

TCB_t* new_task = (TCB_t*)malloc(sizeof(TCB_t));

if (new_task == NULL) return NULL;

// Allocate stack

new_task->stack_ptr = malloc(stack_size);

if (new_task->stack_ptr == NULL) {

free(new_task);

return NULL;

}

// Initialize TCB

new_task->stack_size = stack_size;

new_task->priority = priority;

new_task->state = TASK_READY;

new_task->task_function = task_func;

new_task->task_parameters = parameters;

new_task->time_slice = DEFAULT_TIME_SLICE;

// Initialize stack frame

initialize_stack_frame(new_task);

return new_task;

}

4. Interrupt Handling in RTOS

Interrupt handling is crucial for real-time systems. The RTOS must manage interrupts efficiently while maintaining deterministic behavior. Below is an implementation of a basic interrupt handler:

typedef struct {

void (*isr)(void);

uint8_t priority;

} ISR_Entry_t;

#define MAX_INTERRUPTS 256

ISR_Entry_t isr_table[MAX_INTERRUPTS];

void register_interrupt(uint8_t vector, void (*isr)(void), uint8_t priority) {

if (vector < MAX_INTERRUPTS) {

__disable_interrupts();

isr_table[vector].isr = isr;

isr_table[vector].priority = priority;

__enable_interrupts();

}

}

void interrupt_handler(uint8_t vector) {

if (vector < MAX_INTERRUPTS && isr_table[vector].isr != NULL) {

isr_table[vector].isr();

}

}

- Interrupt Registration: The

register_interrupt()function registers an ISR for a specific interrupt vector. - Interrupt Handling: The

interrupt_handler()function executes the ISR when an interrupt occurs.

5. Timer Management

RTOS timer management provides precise timing services for tasks and system operations. Below is an implementation of a basic timer:

typedef struct {

uint32_t interval;

uint32_t remaining;

bool periodic;

void (*callback)(void*);

void* callback_param;

} Timer_t;

#define MAX_TIMERS 32

Timer_t timer_pool[MAX_TIMERS];

Timer_t* create_timer(uint32_t interval,

bool periodic,

void (*callback)(void*),

void* param) {

Timer_t* timer = NULL;

for (int i = 0; i < MAX_TIMERS; i++) {

if (timer_pool[i].callback == NULL) {

timer = &timer_pool[i];

timer->interval = interval;

timer->remaining = interval;

timer->periodic = periodic;

timer->callback = callback;

timer->callback_param = param;

break;

}

}

return timer;

}

6. Inter-Task Communication

RTOS provides mechanisms for tasks to communicate and synchronize. Below is an implementation of a message queue:

typedef struct {

void* buffer;

size_t msg_size;

size_t queue_length;

size_t count;

size_t head;

size_t tail;

} MessageQueue_t;

MessageQueue_t* create_queue(size_t msg_size, size_t length) {

MessageQueue_t* queue = malloc(sizeof(MessageQueue_t));

if (queue == NULL) return NULL;

queue->buffer = malloc(msg_size * length);

if (queue->buffer == NULL) {

free(queue);

return NULL;

}

queue->msg_size = msg_size;

queue->queue_length = length;

queue->count = 0;

queue->head = 0;

queue->tail = 0;

return queue;

}

7. Memory Management in RTOS

RTOS memory management focuses on deterministic allocation and deallocation. Below is an implementation of a memory pool:

typedef struct {

void* pool;

size_t block_size;

size_t num_blocks;

uint8_t* block_status;

} MemoryPool_t;

MemoryPool_t* create_memory_pool(size_t block_size, size_t num_blocks) {

MemoryPool_t* pool = malloc(sizeof(MemoryPool_t));

if (pool == NULL) return NULL;

pool->pool = malloc(block_size * num_blocks);

if (pool->pool == NULL) {

free(pool);

return NULL;

}

pool->block_status = calloc(num_blocks, sizeof(uint8_t));

if (pool->block_status == NULL) {

free(pool->pool);

free(pool);

return NULL;

}

pool->block_size = block_size;

pool->num_blocks = num_blocks;

return pool;

}

8. Performance Considerations

Key metrics for RTOS performance include:

- Context Switch Time: The time taken to save and restore task contexts during task switching. Typically under 1 microsecond for embedded systems.

- Interrupt Latency: The delay between interrupt occurrence and ISR execution. Should be predictable and minimal, usually less than 100 nanoseconds.

- Task Switch Time: Total time to switch between tasks, including context switching and scheduling overhead. Should be consistent and typically under 5 microseconds.

- Memory Footprint: RTOS kernel size should be minimal, typically 10-100KB depending on features included.

9. Conclusion

RTOS internals form the foundation of reliable real-time systems. Understanding these concepts is crucial for developing deterministic and reliable embedded systems. The key aspects covered—task management, interrupt handling, timing services, and memory management—all work together to provide predictable behavior essential for real-time applications.