Day 40: Linux Kernel Memory Management

Table of Contents

- Introduction to Linux Memory Management

- Physical Memory Management

- Virtual Memory System

- Slab Allocator Deep Dive

- Page Frame Management

- Memory Zones and Node Management

- Kernel Memory Allocation

- Memory Reclamation and Swapping

- Memory Debugging and Monitoring

- Performance Optimization

- Conclusion

1. Introduction to Linux Memory Management

Linux memory management is a complex subsystem responsible for handling everything from physical memory allocation to virtual memory mapping. It ensures efficient memory usage for both user-space and kernel-space operations. The Linux kernel uses a combination of techniques, including page tables, memory zones, and various allocators, to manage memory effectively.

- Page Tables: Maintain mappings between virtual and physical addresses. Linux uses a multi-level page table structure to efficiently manage memory translations.

- Memory Zones: Different regions of memory with specific purposes and accessibility characteristics. For example, DMA zones for device operations and Normal zones for regular memory operations.

- Memory Allocators: Various allocation mechanisms, including the buddy system for page allocation and the slab allocator for kernel objects.

2. Physical Memory Management

The buddy system is the foundation of physical page management in Linux. It divides memory into blocks of varying sizes, allowing efficient allocation and deallocation of memory pages. The buddy system ensures that memory fragmentation is minimized by merging adjacent free blocks.

Buddy System Implementation

Below is a simplified implementation of the buddy system:

#define MAX_ORDER 11

#define PAGE_SIZE 4096

struct free_area {

struct list_head free_list;

unsigned long nr_free;

};

struct zone {

struct free_area free_area[MAX_ORDER];

unsigned long free_pages;

};

void *alloc_pages(unsigned int order) {

struct zone *zone = get_current_zone();

unsigned int current_order;

struct page *page;

for (current_order = order; current_order < MAX_ORDER; current_order++) {

if (!list_empty(&zone->free_area[current_order].free_list)) {

page = list_first_entry(&zone->free_area[current_order].free_list,

struct page, lru);

list_del(&page->lru);

zone->free_area[current_order].nr_free--;

// Split blocks if necessary

while (current_order > order) {

current_order--;

split_page(page, current_order);

}

return page_address(page);

}

}

return NULL;

}

3. Virtual Memory System

Linux implements a demand-paging virtual memory system, which allows processes to use more memory than physically available by swapping pages to and from disk. The virtual memory system also supports shared memory and memory-mapped files.

Page Table Implementation

Below is a simplified implementation of a page table entry:

struct page_table_entry {

unsigned long pfn : 55; // Page Frame Number

unsigned int present : 1;

unsigned int writable : 1;

unsigned int user : 1;

unsigned int accessed : 1;

unsigned int dirty : 1;

unsigned int unused : 4;

};

struct page_table {

struct page_table_entry entries[512];

};

void map_page(unsigned long virtual_addr, unsigned long physical_addr,

unsigned int flags) {

struct page_table *pgt = get_current_page_table();

unsigned int pgt_index = (virtual_addr >> 12) & 0x1FF;

pgt->entries[pgt_index].pfn = physical_addr >> 12;

pgt->entries[pgt_index].present = 1;

pgt->entries[pgt_index].writable = (flags & PAGE_WRITABLE) ? 1 : 0;

pgt->entries[pgt_index].user = (flags & PAGE_USER) ? 1 : 0;

// Flush TLB for this address

flush_tlb_single(virtual_addr);

}

4. Slab Allocator Deep Dive

The slab allocator provides efficient allocation of kernel objects by caching frequently used objects. It reduces fragmentation and improves performance by reusing memory for objects of the same type.

Slab Cache Implementation

Below is a simplified implementation of a slab cache:

struct kmem_cache {

unsigned int object_size; // Size of each object

unsigned int align; // Alignment requirements

unsigned int flags; // Cache flags

const char *name; // Cache name

struct array_cache *array; // Per-CPU object cache

unsigned int buffer_size; // Size of each slab

// Constructors/destructors

void (*ctor)(void *obj);

void (*dtor)(void *obj);

// Slab management

struct list_head slabs_full;

struct list_head slabs_partial;

struct list_head slabs_free;

};

struct kmem_cache *kmem_cache_create(const char *name, size_t size,

size_t align, unsigned long flags,

void (*ctor)(void*)) {

struct kmem_cache *cache;

cache = kzalloc(sizeof(struct kmem_cache), GFP_KERNEL);

if (!cache)

return NULL;

cache->object_size = ALIGN(size, align);

cache->align = align;

cache->flags = flags;

cache->name = name;

cache->ctor = ctor;

INIT_LIST_HEAD(&cache->slabs_full);

INIT_LIST_HEAD(&cache->slabs_partial);

INIT_LIST_HEAD(&cache->slabs_free);

return cache;

}

5. Page Frame Management

Linux maintains detailed information about each physical page frame in the system. The struct page structure is used to track the state of each page.

Page Frame Tracking

Below is a simplified implementation of page frame tracking:

struct page {

unsigned long flags;

atomic_t _count;

atomic_t _mapcount;

unsigned int order;

struct list_head lru;

struct address_space *mapping;

pgoff_t index;

void *virtual; // Page virtual address

};

void init_page_tracking(void) {

unsigned long i;

struct page *page;

for (i = 0; i < num_physpages; i++) {

page = &mem_map[i];

atomic_set(&page->_count, 0);

atomic_set(&page->_mapcount, -1);

page->flags = 0;

page->order = 0;

INIT_LIST_HEAD(&page->lru);

}

}

6. Memory Zones and Node Management

Linux divides physical memory into zones for different purposes, such as DMA, Normal, and HighMem. Each zone has its own characteristics and usage constraints.

Zone Management Implementation

Below is a simplified implementation of zone management:

struct zone {

unsigned long watermark[NR_WMARK];

unsigned long nr_pages;

unsigned long spanned_pages;

unsigned long present_pages;

struct free_area free_area[MAX_ORDER];

spinlock_t lock;

// Per-zone statistics

atomic_long_t vm_stat[NR_VM_ZONE_STAT_ITEMS];

// Zone compaction

unsigned long compact_cached_free_pfn;

unsigned long compact_cached_migrate_pfn;

};

void zone_init(struct zone *zone, unsigned long start_pfn,

unsigned long size) {

int i;

zone->nr_pages = size;

zone->spanned_pages = size;

zone->present_pages = size;

for (i = 0; i < MAX_ORDER; i++) {

INIT_LIST_HEAD(&zone->free_area[i].free_list);

zone->free_area[i].nr_free = 0;

}

spin_lock_init(&zone->lock);

}

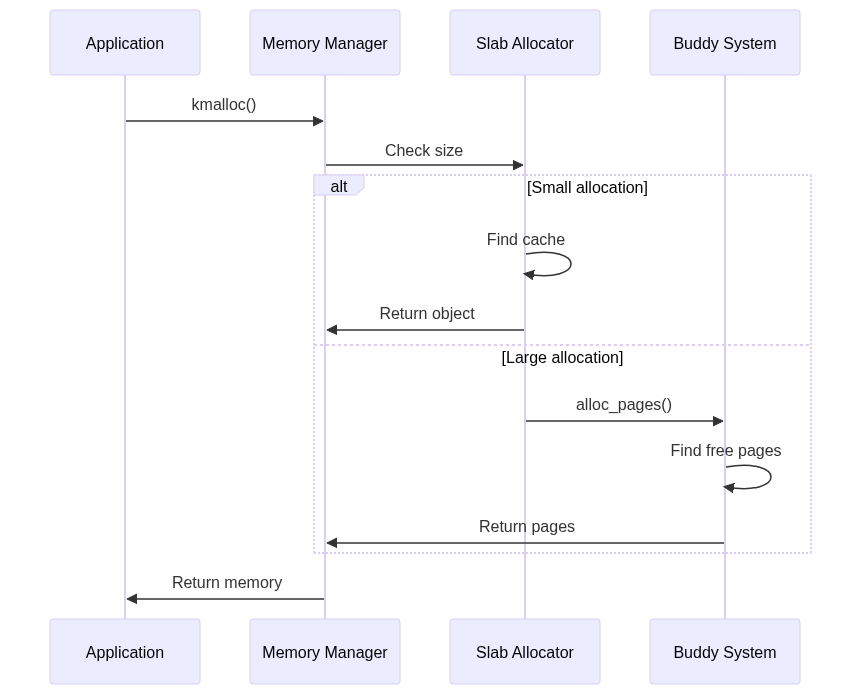

7. Kernel Memory Allocation

The Linux kernel provides various methods for allocating memory, including kmalloc() for small allocations and alloc_pages() for larger allocations.

KMALLOC Implementation

Below is a simplified implementation of kmalloc():

void *kmalloc(size_t size, gfp_t flags) {

struct kmem_cache *cache;

void *ret = NULL;

// Find appropriate cache for this size

if (size <= 8) cache = kmalloc_caches[0];

else if (size <= 16) cache = kmalloc_caches[1];

else if (size <= 32) cache = kmalloc_caches[2];

else if (size <= 64) cache = kmalloc_caches[3];

else if (size <= 128) cache = kmalloc_caches[4];

else {

// Use page allocator for large allocations

int order = get_order(size);

ret = alloc_pages(flags, order);

if (ret)

ret = page_address(ret);

return ret;

}

ret = kmem_cache_alloc(cache, flags);

return ret;

}

8. Memory Reclamation and Swapping

Linux implements various mechanisms to reclaim memory when needed, including swapping and page reclamation.

Page Reclaim Implementation

Below is a simplified implementation of page reclamation:

struct scan_control {

unsigned long nr_to_reclaim;

unsigned long nr_reclaimed;

unsigned long nr_scanned;

unsigned int priority;

unsigned int may_writepage:1;

unsigned int may_unmap:1;

unsigned int may_swap:1;

};

unsigned long try_to_free_pages(struct zone *zone,

unsigned int order,

gfp_t gfp_mask) {

struct scan_control sc = {

.nr_to_reclaim = SWAP_CLUSTER_MAX,

.priority = DEF_PRIORITY,

.may_writepage = 1,

.may_unmap = 1,

.may_swap = 1,

};

unsigned long nr_reclaimed = 0;

do {

nr_reclaimed += shrink_inactive_list(zone, &sc);

if (nr_reclaimed >= sc.nr_to_reclaim)

break;

nr_reclaimed += shrink_active_list(zone, &sc);

} while (nr_reclaimed < sc.nr_to_reclaim);

return nr_reclaimed;

}

9. Memory Debugging and Monitoring

Linux provides tools and mechanisms for debugging and monitoring memory usage, such as vmstat, slabtop, and kmemleak.

Memory Allocation

10. Performance Optimization

Key optimization strategies for Linux memory management include:

- Memory Compaction: Reduces fragmentation by moving pages to create larger contiguous blocks.

- Transparent Huge Pages: Reduces TLB pressure by using larger page sizes for appropriate workloads.

- NUMA Awareness: Ensures memory allocations are made from nodes closest to the CPU using the memory.

- Slab Coloring: Improves cache utilization by adding offsets to object positions within slabs.

11. Conclusion

Linux kernel memory management is a sophisticated system that provides efficient memory allocation and management for both kernel and user space. Understanding its internals is crucial for kernel development and system optimization.