Day 51: Kernel Error Handling in Depth - From Exceptions to Recovery

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Fundamentals of Kernel Error Handling

- Exception Handling Architecture

- Kernel Panic and Recovery

- System Call Error Handling

- Error Logging and Debugging

- Implementation Examples

- Performance Considerations

- Best Practices

- Code Examples

- Conclusion

1. Introduction

Error handling in kernel mechanisms is one of the most critical aspects of operating system design. The kernel is the core of the operating system, responsible for managing hardware resources, processes, and memory. When errors occur at this level, they can lead to system crashes, data corruption, or security vulnerabilities. This article explores the intricate details of how modern operating systems handle errors at the kernel level, focusing on exception management, recovery strategies, and best practices for robust error handling.

2. Fundamentals of Kernel Error Handling

Kernel error handling operates on multiple levels, each requiring a different approach to ensure system stability and reliability.

Hardware Level Errors

Hardware-level errors occur at the CPU level and include events like page faults, division by zero, and illegal instructions. These errors are generated directly by the processor and must be handled immediately by the kernel. The handling process involves saving the current state of the CPU, switching to kernel mode, and executing the appropriate exception handler. For example, a page fault might trigger the kernel to load the missing page from disk, while a division by zero might terminate the offending process.

Software Level Errors

Software-level errors occur during kernel execution and include invalid parameters, resource allocation failures, and timing violations. These errors are typically detected by the kernel itself and must be handled gracefully to prevent system crashes. For instance, if a memory allocation fails, the kernel might return an error code to the calling function instead of crashing the system.

System Call Errors

System calls are the interface between user-space applications and the kernel. When a system call fails, the kernel must communicate the error back to the user-space application while maintaining system stability. This involves returning appropriate error codes and ensuring that resources are properly cleaned up.

3. Exception Handling Architecture

Hardware Exception Mechanisms

The x86 architecture provides several mechanisms for handling hardware exceptions, including the Interrupt Descriptor Table (IDT). The IDT contains entries for each exception type, specifying the handler function to be executed when the exception occurs.

// Interrupt Descriptor Table (IDT) structure

struct idt_entry {

uint16_t offset_low;

uint16_t segment_selector;

uint8_t zero;

uint8_t type_attributes;

uint16_t offset_high;

} __attribute__((packed));

// IDT initialization example

void init_idt_entry(struct idt_entry* entry, uint32_t handler, uint16_t selector, uint8_t flags) {

entry->offset_low = handler & 0xFFFF;

entry->segment_selector = selector;

entry->zero = 0;

entry->type_attributes = flags;

entry->offset_high = (handler >> 16) & 0xFFFF;

}

The init_idt_entry function initializes an IDT entry with the address of the exception handler and the necessary flags. This ensures that the CPU can correctly route exceptions to the appropriate handler.

Software Exception Handling

The kernel implements software exception handling through various mechanisms, such as error codes and handler functions. The kernel_error structure represents an error, including the error code, message, and handler function.

// Example of kernel error handling structure

struct kernel_error {

int error_code;

const char* message;

void (*handler)(void*);

void* context;

};

// Error handler registration

static struct kernel_error error_handlers[MAX_ERROR_HANDLERS];

int register_error_handler(int error_code, void (*handler)(void*)) {

if (error_code >= MAX_ERROR_HANDLERS)

return -EINVAL;

error_handlers[error_code].handler = handler;

return 0;

}

The register_error_handler function allows the kernel to register handler functions for specific error codes. When an error occurs, the kernel can invoke the appropriate handler to manage the error.

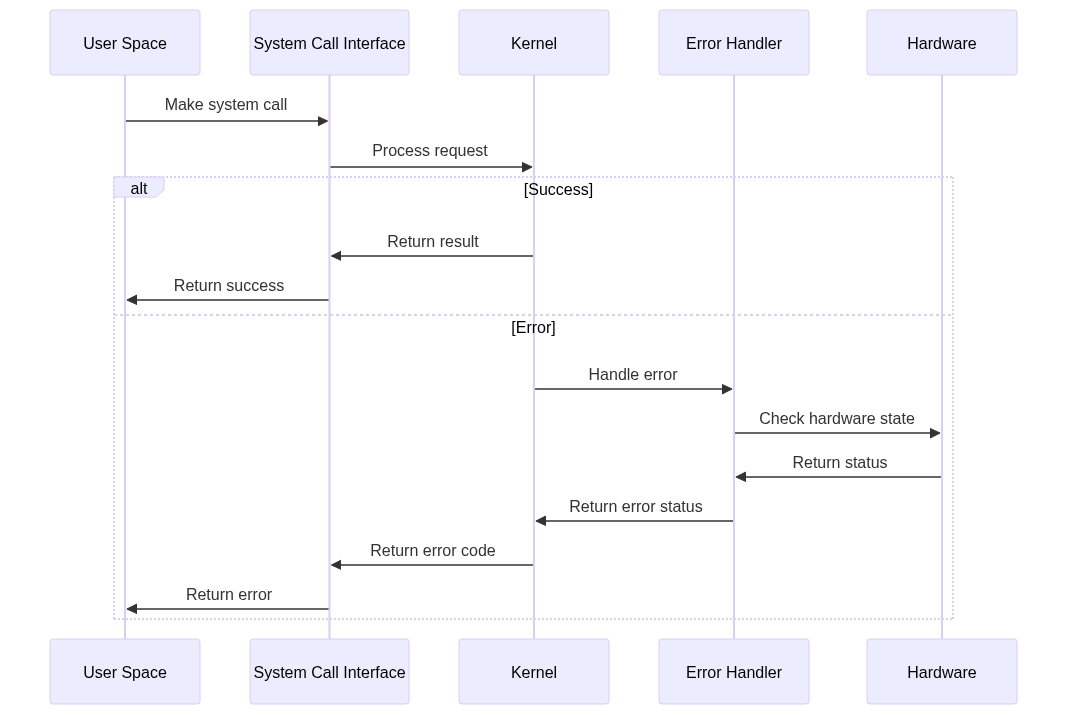

This diagram shows how errors are propagated from user space to the kernel and back, ensuring that errors are handled gracefully.

4. Kernel Panic and Recovery

When severe errors occur, the kernel may enter a panic state. A kernel panic is a safety measure that prevents further damage to the system by halting all operations. The following code demonstrates a basic kernel panic handler:

void kernel_panic(const char* message) {

// Disable interrupts

__asm__ volatile("cli");

// Log the panic message

printk(KERN_EMERG "Kernel panic: %s\n", message);

// Dump stack trace

dump_stack();

// Stop all CPUs

stop_other_cpus();

// Halt the system

while(1) {

__asm__ volatile("hlt");

}

}

The kernel_panic function disables interrupts, logs the panic message, dumps the stack trace, and halts the system. This ensures that the system does not continue executing in an unstable state.

5. System Call Error Handling

System calls must handle errors robustly to ensure that user-space applications receive meaningful feedback and that the system remains stable. The following example demonstrates a system call with error handling:

// Example system call with error handling

long sys_example(int param) {

if (param < 0)

return -EINVAL;

void* mem = kmalloc(param, GFP_KERNEL);

if (!mem)

return -ENOMEM;

// Process the request

int result = process_data(mem);

if (result < 0) {

kfree(mem);

return result;

}

kfree(mem);

return 0;

}

The sys_example function checks for invalid parameters, handles memory allocation failures, and ensures that resources are properly cleaned up. This approach prevents resource leaks and ensures that the system remains stable.

6. Error Logging and Debugging

Error logging is essential for diagnosing and debugging kernel issues. The following code demonstrates a simple kernel logging mechanism:

struct kernel_log_entry {

uint64_t timestamp;

int level;

char message[256];

char function[64];

int line;

};

#define MAX_LOG_ENTRIES 1024

static struct kernel_log_entry log_buffer[MAX_LOG_ENTRIES];

static int log_index = 0;

void kernel_log(int level, const char* func, int line, const char* fmt, ...) {

struct kernel_log_entry* entry = &log_buffer[log_index % MAX_LOG_ENTRIES];

entry->timestamp = get_timestamp();

entry->level = level;

entry->line = line;

strncpy(entry->function, func, sizeof(entry->function) - 1);

va_list args;

va_start(args, fmt);

vsnprintf(entry->message, sizeof(entry->message), fmt, args);

va_end(args);

log_index++;

}

The kernel_log function logs error messages with a timestamp, log level, function name, and line number. This information is invaluable for debugging and diagnosing kernel issues.

7. Implementation Examples

The following code demonstrates a complete error handling subsystem:

// Error codes

#define ERR_MEMORY 1

#define ERR_IO 2

#define ERR_PERMISSION 3

#define ERR_TIMEOUT 4

// Error handling context

struct error_context {

int error_code;

void* data;

void (*cleanup)(void*);

};

// Error handler function type

typedef int (*error_handler_t)(struct error_context*);

// Error handler registration

static error_handler_t handlers[MAX_ERROR_CODES];

int register_handler(int error_code, error_handler_t handler) {

if (error_code >= MAX_ERROR_CODES)

return -EINVAL;

handlers[error_code] = handler;

return 0;

}

// Error handling execution

int handle_error(struct error_context* ctx) {

if (!ctx || ctx->error_code >= MAX_ERROR_CODES)

return -EINVAL;

error_handler_t handler = handlers[ctx->error_code];

if (!handler)

return -ENOSYS;

return handler(ctx);

}

This implementation allows the kernel to register handler functions for specific error codes and execute them when errors occur.

8. Performance Considerations

Error handling must be efficient to minimize the impact on system performance. The following code demonstrates a performance-optimized error handler:

// Fast path error checking

static inline int fast_error_check(const void* ptr) {

if (__builtin_expect(!ptr, 0))

return -EINVAL;

return 0;

}

// Performance-optimized error handling

int optimized_error_handler(void* data, size_t size) {

int ret = fast_error_check(data);

if (ret)

return ret;

// Use likely/unlikely macros for better branch prediction

if (__builtin_unlikely(size > MAX_SIZE))

return -EINVAL;

return process_data(data, size);

}

The optimized_error_handler function uses branch prediction hints to minimize the performance impact of error checking.

9. Best Practices

Here are some best practices for kernel error handling:

- Always check return values: Ensure that all function calls are checked for errors.

- Use appropriate error codes: Return meaningful error codes to user-space applications.

- Clean up resources in reverse order: Ensure that resources are properly released in case of an error.

- Log meaningful error messages: Provide detailed error messages for debugging.

- Implement proper error recovery: Attempt to recover from errors whenever possible.

- Consider error propagation: Ensure that errors are propagated correctly through the call stack.

- Handle out-of-memory conditions: Always check for memory allocation failures.

- Implement timeout mechanisms: Prevent infinite loops or hangs by using timeouts.

- Use atomic operations where necessary: Ensure that critical sections are protected from race conditions.

- Maintain error consistency: Ensure that error handling is consistent across the kernel.

10. Code Examples

The following code demonstrates a complete error handling module for the Linux kernel:

#include <linux/kernel.h>

#include <linux/module.h>

#include <linux/slab.h>

#include <linux/errno.h>

MODULE_LICENSE("GPL");

MODULE_AUTHOR("Your Name");

MODULE_DESCRIPTION("Error Handling Example Module");

// Error handling structure

struct error_handler {

struct list_head list;

int error_code;

int (*handler)(void* data);

};

// Global error handler list

static LIST_HEAD(error_handlers);

static DEFINE_SPINLOCK(handlers_lock);

// Register an error handler

int register_error_handler(int error_code, int (*handler)(void* data)) {

struct error_handler* eh;

eh = kmalloc(sizeof(*eh), GFP_KERNEL);

if (!eh)

return -ENOMEM;

eh->error_code = error_code;

eh->handler = handler;

spin_lock(&handlers_lock);

list_add(&eh->list, &error_handlers);

spin_unlock(&handlers_lock);

return 0;

}

// Handle an error

int handle_error(int error_code, void* data) {

struct error_handler* eh;

int ret = -ENOSYS;

spin_lock(&handlers_lock);

list_for_each_entry(eh, &error_handlers, list) {

if (eh->error_code == error_code) {

ret = eh->handler(data);

break;

}

}

spin_unlock(&handlers_lock);

return ret;

}

// Example error handler

static int example_handler(void* data) {

printk(KERN_INFO "Handling error with data: %p\n", data);

return 0;

}

// Module initialization

static int __init error_handler_init(void) {

int ret;

ret = register_error_handler(1, example_handler);

if (ret)

return ret;

printk(KERN_INFO "Error handling module initialized\n");

return 0;

}

// Module cleanup

static void __exit error_handler_exit(void) {

struct error_handler *eh, *tmp;

spin_lock(&handlers_lock);

list_for_each_entry_safe(eh, tmp, &error_handlers, list) {

list_del(&eh->list);

kfree(eh);

}

spin_unlock(&handlers_lock);

printk(KERN_INFO "Error handling module unloaded\n");

}

module_init(error_handler_init);

module_exit(error_handler_exit);

This module demonstrates how to register and handle errors in the Linux kernel.

11. Conclusion

Error handling in kernel mechanisms is a critical component of operating system design. Proper implementation ensures system stability, reliability, and security. The techniques and patterns discussed in this article provide a foundation for robust error handling in kernel development. By following best practices and leveraging the provided code examples, developers can create resilient and efficient kernel error handling mechanisms.