Day 57: Fault Tolerance in Modern Operating Systems: Principles and Practices

Table of Content

- Introduction

- Understanding Fault Tolerance

- Types of Faults

- Recovery Techniques

- System Architecture

- Performance Considerations

- Conclusion

1. Introduction

Fault tolerance is a critical aspect of modern operating systems that ensures system reliability and continuous operation even in the presence of hardware or software failures. This article explores the intricate details of fault tolerance mechanisms, focusing specifically on recovery techniques. Fault tolerance is essential for systems that require high availability, such as financial systems, healthcare systems, and cloud computing platforms.

The primary goal of fault tolerance is to ensure that a system can continue operating correctly even when some components fail. This is achieved through hardware and software techniques that detect, isolate, and recover from faults. By implementing fault tolerance mechanisms, operating systems can provide uninterrupted service, maintain data integrity, and prevent catastrophic failures.

2. Understanding Fault Tolerance

Fault tolerance refers to the ability of a system to continue functioning properly even when one or more of its components fail. The primary objectives are:

-

Service Continuity: Ensuring uninterrupted system operation. This involves maintaining system availability even during component failures through redundancy and failover mechanisms. For example, if a primary server fails, a backup server automatically takes over without service interruption.

-

Data Integrity: Protecting against data corruption or loss. This ensures that all data remains consistent and accurate despite system failures. This is achieved through techniques like checksums, error-correcting codes, and redundant storage.

-

Error Detection: Identifying faults before they cause system failure. Implementing monitoring systems that can detect potential failures through various metrics like CPU usage, memory consumption, and error logs.

Fault tolerance is particularly important in systems where downtime or data loss can have severe consequences. For example, in a banking system, a failure could result in financial losses or compromised customer data. Fault tolerance mechanisms help mitigate these risks by ensuring that the system can recover quickly from failures and continue to operate correctly.

3. Types of Faults

Understanding different types of faults is crucial for implementing appropriate recovery mechanisms:

-

Transient Faults: These are temporary faults that occur once and disappear. Examples include memory bit flips due to cosmic radiation or electromagnetic interference. Detection typically involves retry mechanisms. For example, if a memory read operation fails due to a transient fault, the system can retry the operation, and it may succeed the second time.

-

Intermittent Faults: These faults occur periodically due to unstable hardware or software conditions. They require continuous monitoring and pattern recognition for detection. For example, a faulty network interface card might cause intermittent connectivity issues that are difficult to diagnose.

-

Permanent Faults: These are persistent faults that require component replacement or major system reconfiguration. Examples include hardware failures like disk crashes or CPU failures. Permanent faults typically require manual intervention to resolve, such as replacing a failed hard drive.

Each type of fault requires a different approach to detection and recovery. Transient faults can often be resolved by retrying the operation, while intermittent faults may require more sophisticated monitoring and diagnostic tools. Permanent faults, on the other hand, usually require hardware replacement or system reconfiguration.

4. Recovery Techniques

4.1 Checkpoint-based Recovery

Checkpoint-based recovery involves periodically saving the state of a system so that it can be restored in the event of a failure. This technique is particularly useful for long-running processes that cannot afford to start over from the beginning in case of a failure.

Here’s a basic implementation of a checkpoint mechanism in C:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <signal.h>

#include <string.h>

typedef struct {

int process_state;

void* memory_snapshot;

size_t snapshot_size;

} Checkpoint;

Checkpoint* create_checkpoint(void* data, size_t size) {

Checkpoint* cp = malloc(sizeof(Checkpoint));

cp->process_state = 1;

cp->snapshot_size = size;

cp->memory_snapshot = malloc(size);

memcpy(cp->memory_snapshot, data, size);

return cp;

}

void restore_checkpoint(Checkpoint* cp, void* data) {

if (cp && cp->memory_snapshot) {

memcpy(data, cp->memory_snapshot, cp->snapshot_size);

}

}

void free_checkpoint(Checkpoint* cp) {

if (cp) {

free(cp->memory_snapshot);

free(cp);

}

}

// Example usage

int main() {

int data[5] = {1, 2, 3, 4, 5};

// Create checkpoint

Checkpoint* cp = create_checkpoint(data, sizeof(data));

// Modify data

data[0] = 100;

printf("Modified data: %d\n", data[0]);

// Restore checkpoint

restore_checkpoint(cp, data);

printf("Restored data: %d\n", data[0]);

free_checkpoint(cp);

return 0;

}

In this example, the create_checkpoint function saves the current state of the data array, while the restore_checkpoint function restores the state from the checkpoint. This allows the system to recover from a failure by restoring the state to a previously saved checkpoint.

4.2 Log-based Recovery

Log-based recovery involves recording all changes to the system state in a log file. In the event of a failure, the system can replay the log to restore the state to its last consistent state. This technique is commonly used in database systems to ensure data integrity.

Implementation example of a basic logging mechanism:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <time.h>

#include <string.h>

#define LOG_FILE "system.log"

#define MAX_LOG_SIZE 1024

typedef struct {

time_t timestamp;

char message[256];

int severity;

} LogEntry;

void write_log(const char* message, int severity) {

FILE* file = fopen(LOG_FILE, "a");

if (file) {

LogEntry entry;

entry.timestamp = time(NULL);

strncpy(entry.message, message, sizeof(entry.message) - 1);

entry.severity = severity;

fwrite(&entry, sizeof(LogEntry), 1, file);

fclose(file);

}

}

void recover_from_log() {

FILE* file = fopen(LOG_FILE, "r");

if (file) {

LogEntry entry;

while (fread(&entry, sizeof(LogEntry), 1, file) == 1) {

printf("Timestamp: %ld, Severity: %d, Message: %s\n",

entry.timestamp, entry.severity, entry.message);

}

fclose(file);

}

}

int main() {

write_log("System started", 1);

write_log("Operation completed", 2);

printf("Recovery log:\n");

recover_from_log();

return 0;

}

In this example, the write_log function writes log entries to a file, while the recover_from_log function reads the log entries and prints them. In a real system, the log entries would be used to restore the system state after a failure.

4.3 Process Pairs

Process pairs involve running two identical processes in parallel, with one acting as the primary and the other as the backup. If the primary process fails, the backup process can take over immediately. This technique is commonly used in high-availability systems where downtime is not acceptable.

4.4 N-Version Programming

N-version programming involves running multiple versions of the same software in parallel and comparing their outputs. If one version produces an incorrect result, the system can use the result from another version. This technique is particularly useful for critical systems where software bugs could have severe consequences.

5. System Architecture

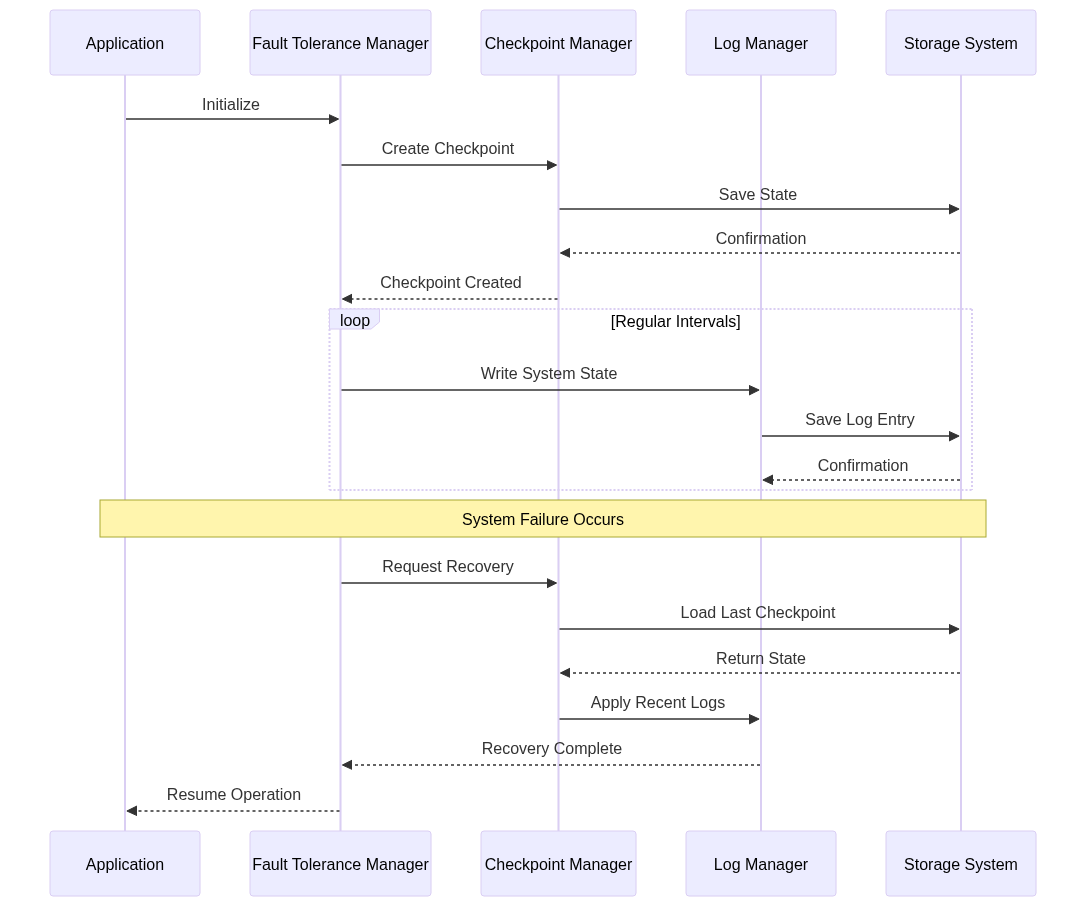

The system architecture for fault tolerance typically includes several components, such as a fault tolerance manager, checkpoint manager, log manager, and storage system. These components work together to detect faults, save system state, and recover from failures.

In this architecture, the fault tolerance manager coordinates the checkpoint and log managers to save the system state and recover from failures. The storage system is used to store checkpoints and log entries, ensuring that the system can recover even after a complete failure.

6. Performance Considerations

Key metrics for fault tolerance mechanisms:

-

Recovery Time Objective (RTO): This is the maximum acceptable time required to restore system operation after a failure. For critical systems, RTO might be measured in seconds or minutes.

-

Recovery Point Objective (RPO): This defines the maximum acceptable data loss measured in time. For example, an RPO of 5 minutes means you might lose up to 5 minutes of data in case of failure.

-

Overhead Impact: The performance impact of fault tolerance mechanisms during normal operation. This includes CPU usage, memory consumption, and storage requirements for checkpoints and logs.

These metrics are crucial for designing fault tolerance mechanisms that meet the requirements of the system. For example, a system with a low RTO might require more frequent checkpoints, while a system with a low RPO might require more detailed logging.

7. Conclusion

Fault tolerance mechanisms are essential for building reliable and robust operating systems. The combination of checkpoint-based and log-based recovery techniques, along with proper monitoring and error detection, provides a comprehensive approach to handling system failures. By implementing these mechanisms, operating systems can ensure service continuity, maintain data integrity, and prevent catastrophic failures.