Day 59: Containerization Internals - Deep Dive into Namespace Implementation

1. Introduction

Containerization internals, particularly namespace implementation, form modern container technologies’ backbone. This article explores the low-level details of how namespaces are implemented in the Linux kernel and how they enable container isolation. Namespaces are a fundamental feature of Linux that allow the partitioning of kernel resources so that one set of processes sees one set of resources while another set of processes sees a different set of resources.

Namespaces are essential for creating lightweight, isolated environments that are the foundation of containerization technologies like Docker and Kubernetes. By understanding how namespaces work at a deep level, developers and system administrators can better manage and optimize containerized applications.

2. Namespace Fundamentals

Core concepts of namespace implementation:

-

Namespace Structure: A namespace wraps global system resources in an abstraction that makes it appear to processes within the namespace that they have their own isolated instance of the resource. The kernel maintains separate data structures for each namespace type. For example, each PID namespace has its own process ID space, allowing processes in different namespaces to have the same PID without conflict.

-

Resource Isolation: Each namespace creates a new view of specific system resources, allowing processes within the namespace to operate independently without interfering with processes in other namespaces. This isolation is crucial for ensuring that containers do not interfere with each other or with the host system.

-

Namespace Hierarchy: Namespaces can be nested, creating a hierarchical structure where child namespaces inherit properties from their parents but can be configured independently. This allows for more complex and flexible container configurations, such as nested containers or multi-tenant environments.

Understanding these core concepts is essential for working with namespaces and containerization technologies. By leveraging namespaces, developers can create isolated environments that are both secure and efficient.

3. Types of Namespaces

3.1 Implementation Example of Mount Namespace

Mount namespaces isolate the set of filesystem mount points seen by a group of processes. This allows each container to have its own filesystem view, independent of the host and other containers.

Here’s an example of creating a new mount namespace:

#include <sched.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <sys/wait.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <sys/mount.h>

#include <sys/stat.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

#define STACK_SIZE (1024 * 1024)

// Function to be executed in new namespace

static int child_func(void* arg) {

printf("Child process PID: %d\n", getpid());

// Create a new mount point

mkdir("/mnt/new_root", 0755);

// Mount a tmpfs filesystem

if (mount("none", "/mnt/new_root", "tmpfs", 0, NULL) == -1) {

perror("mount");

return 1;

}

printf("New mount namespace created\n");

// Keep the process running

sleep(60);

return 0;

}

int main() {

char* stack = malloc(STACK_SIZE);

if (!stack) {

perror("malloc");

exit(1);

}

printf("Parent process PID: %d\n", getpid());

// Create new namespace

pid_t pid = clone(child_func,

stack + STACK_SIZE,

CLONE_NEWNS | SIGCHLD,

NULL);

if (pid == -1) {

perror("clone");

exit(1);

}

// Wait for child process

waitpid(pid, NULL, 0);

free(stack);

return 0;

}

In this example, the clone system call is used to create a new mount namespace. The child process creates a new mount point and mounts a tmpfs filesystem, which is isolated from the parent process. This demonstrates how mount namespaces can be used to create isolated filesystem views for containers.

3.2 Network Namespace Implementation

Network namespaces isolate network interfaces, IP addresses, routing tables, and other network resources. This allows each container to have its own network stack, independent of the host and other containers.

Here’s an example of creating a new network namespace:

#include <sched.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <sys/wait.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <net/if.h>

#include <arpa/inet.h>

#include <sys/ioctl.h>

#define STACK_SIZE (1024 * 1024)

static int child_func(void* arg) {

printf("Network namespace child PID: %d\n", getpid());

// Create a network interface structure

struct ifreq ifr;

int sockfd = socket(AF_INET, SOCK_DGRAM, 0);

if (sockfd < 0) {

perror("socket");

return 1;

}

// Get list of interfaces in new namespace

memset(&ifr, 0, sizeof(ifr));

strcpy(ifr.ifr_name, "lo");

// Bring up loopback interface

ifr.ifr_flags |= IFF_UP;

if (ioctl(sockfd, SIOCSIFFLAGS, &ifr) < 0) {

perror("ioctl");

return 1;

}

printf("Loopback interface configured in new namespace\n");

close(sockfd);

sleep(60);

return 0;

}

int main() {

char* stack = malloc(STACK_SIZE);

if (!stack) {

perror("malloc");

exit(1);

}

printf("Parent process PID: %d\n", getpid());

// Create new network namespace

pid_t pid = clone(child_func,

stack + STACK_SIZE,

CLONE_NEWNET | SIGCHLD,

NULL);

if (pid == -1) {

perror("clone");

exit(1);

}

waitpid(pid, NULL, 0);

free(stack);

return 0;

}

In this example, the clone system call is used to create a new network namespace. The child process configures the loopback interface within the new namespace, demonstrating how network namespaces can be used to create isolated network environments for containers.

4. Namespace API Implementation

The Linux kernel provides a set of system calls and APIs for managing namespaces. These APIs allow developers to create, manage, and manipulate namespaces programmatically.

Here’s a comprehensive example of namespace management:

#include <sched.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <sys/wait.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <fcntl.h>

#include <string.h>

#define STACK_SIZE (1024 * 1024)

struct namespace_config {

int flags;

char* hostname;

char* root_dir;

};

static int setup_namespace(struct namespace_config* config) {

// Set hostname in UTS namespace

if (config->flags & CLONE_NEWUTS) {

if (sethostname(config->hostname, strlen(config->hostname)) == -1) {

perror("sethostname");

return -1;

}

}

// Setup mount namespace

if (config->flags & CLONE_NEWNS) {

if (mount(NULL, "/", NULL, MS_REC | MS_PRIVATE, NULL) == -1) {

perror("mount");

return -1;

}

if (chroot(config->root_dir) == -1) {

perror("chroot");

return -1;

}

}

return 0;

}

static int child_func(void* arg) {

struct namespace_config* config = (struct namespace_config*)arg;

if (setup_namespace(config) == -1) {

return 1;

}

printf("Child process in new namespace\n");

printf("Hostname: %s\n", config->hostname);

printf("Root directory: %s\n", config->root_dir);

// Execute shell in new namespace

execl("/bin/bash", "/bin/bash", NULL);

perror("execl");

return 1;

}

int create_namespace(struct namespace_config* config) {

char* stack = malloc(STACK_SIZE);

if (!stack) {

perror("malloc");

return -1;

}

printf("Creating new namespace with flags: %d\n", config->flags);

pid_t pid = clone(child_func,

stack + STACK_SIZE,

config->flags | SIGCHLD,

config);

if (pid == -1) {

perror("clone");

free(stack);

return -1;

}

waitpid(pid, NULL, 0);

free(stack);

return 0;

}

int main() {

struct namespace_config config = {

.flags = CLONE_NEWUTS | CLONE_NEWNS | CLONE_NEWPID,

.hostname = "container",

.root_dir = "/container_root"

};

return create_namespace(&config);

}

In this example, the create_namespace function creates a new namespace with the specified configuration. The setup_namespace function configures the namespace by setting the hostname and mounting a new root filesystem. The child process then executes a shell within the new namespace, demonstrating how namespaces can be used to create isolated environments.

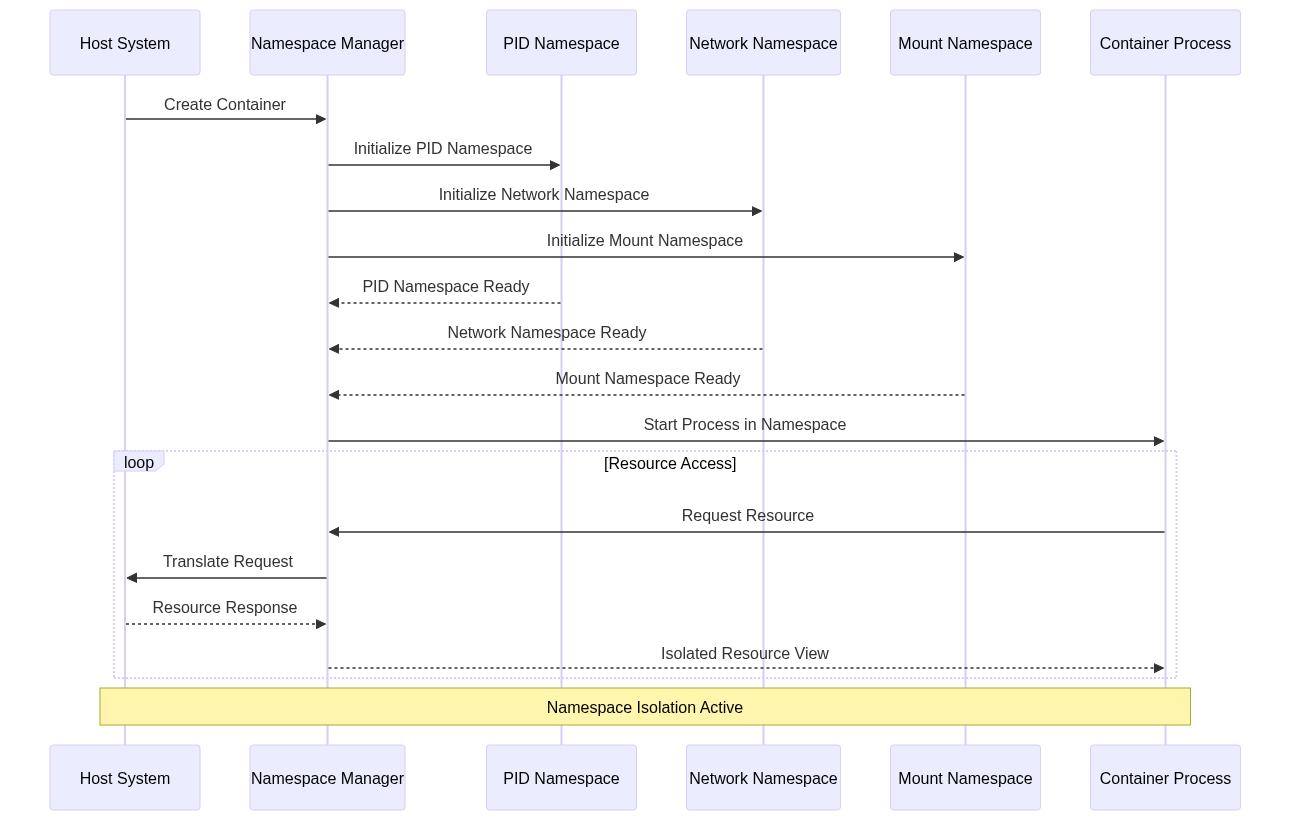

5. System Architecture

The system architecture for namespace management typically involves several components, including the host system, namespace manager, and various namespaces (e.g., PID, network, mount). These components work together to create and manage isolated environments for containers.

In this architecture, the namespace manager coordinates creating and initializing various namespaces. Once the namespaces are ready, the container process is started within the isolated environment. The namespace manager handles resource requests from the container process, ensuring that they are translated and isolated from the host system.

6. Performance Considerations

Key aspects of namespace performance:

-

Creation Overhead: The time and resource cost of creating new namespaces, including memory allocation and initialization of namespace-specific data structures. This impacts container startup time.

-

Context Switching: The overhead of switching between different namespaces when processes need to access resources. This includes the cost of namespace lookup and permission checking.

-

Resource Isolation Impact: The performance impact of maintaining separate resource views for each namespace, including memory overhead and CPU cycles used for namespace management.

These performance considerations are crucial for optimizing containerized applications. By minimizing the overhead of namespace creation and context switching, developers can improve the performance and scalability of their container environments.

7. Security Considerations

Critical security aspects:

-

Privilege Separation: Ensuring proper isolation between namespaces to prevent unauthorized access to resources. This includes implementing proper capability checks and security contexts.

-

Resource Limits: Implementing and enforcing resource limits within namespaces to prevent denial-of-service attacks and resource exhaustion.

-

Namespace Escape Prevention: Implementing safeguards to prevent processes from breaking out of their assigned namespaces through various attack vectors.

Security is a critical consideration when working with namespaces and containerization technologies. By implementing proper isolation and resource limits, developers can ensure that their container environments are secure and resilient to attacks.

8. Conclusion

Understanding namespace implementation is crucial for working with container technologies. The proper implementation of namespaces provides the foundation for secure and efficient container isolation. By leveraging namespaces, developers can create isolated environments that are both secure and efficient, enabling the development of robust and scalable containerized applications.