Day 60: Kernel Synchronization Primitives - Understanding Spinlocks and RCU

1. Introduction

Kernel synchronization primitives are fundamental mechanisms that ensure data consistency and prevent race conditions in operating system kernels. This guide focuses on spinlocks and RCU (Read-Copy-Update), two critical synchronization mechanisms used in modern kernels. Spinlocks are simple, low-level locks that are efficient for short critical sections, while RCU is a more sophisticated mechanism that allows for highly concurrent read access with minimal overhead.

Understanding these synchronization primitives is essential for developing efficient and reliable kernel code. By leveraging spinlocks and RCU, developers can ensure that their kernel code is both performant and free from race conditions, even in highly concurrent environments.

2. Spinlock Implementation

2.1 Basic Spinlock Implementation

Spinlocks are a type of lock that causes a thread to wait in a loop (or “spin”) while repeatedly checking if the lock is available. They are particularly useful in scenarios where the expected wait time is short, as they avoid the overhead of context switching.

Here’s a basic implementation of a spinlock in C:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <pthread.h>

#include <stdatomic.h>

#include <stdbool.h>

#include <unistd.h>

typedef struct {

atomic_flag locked;

} spinlock_t;

void spinlock_init(spinlock_t *lock) {

atomic_flag_clear(&lock->locked);

}

void spinlock_lock(spinlock_t *lock) {

while (atomic_flag_test_and_set(&lock->locked)) {

// CPU yield to prevent excessive power consumption

__asm__ volatile("pause" ::: "memory");

}

}

void spinlock_unlock(spinlock_t *lock) {

atomic_flag_clear(&lock->locked);

}

// Advanced spinlock with backoff

typedef struct {

atomic_flag locked;

unsigned int backoff_min;

unsigned int backoff_max;

} adaptive_spinlock_t;

void adaptive_spinlock_init(adaptive_spinlock_t *lock) {

atomic_flag_clear(&lock->locked);

lock->backoff_min = 4;

lock->backoff_max = 1024;

}

void adaptive_spinlock_lock(adaptive_spinlock_t *lock) {

unsigned int backoff = lock->backoff_min;

while (1) {

if (!atomic_flag_test_and_set(&lock->locked)) {

return;

}

// Exponential backoff

for (unsigned int i = 0; i < backoff; i++) {

__asm__ volatile("pause" ::: "memory");

}

backoff = (backoff << 1);

if (backoff > lock->backoff_max) {

backoff = lock->backoff_max;

}

}

}

// Example usage with performance monitoring

#include <time.h>

typedef struct {

long long lock_attempts;

long long lock_collisions;

double average_wait_time;

} spinlock_stats_t;

typedef struct {

spinlock_t lock;

spinlock_stats_t stats;

} monitored_spinlock_t;

void monitored_spinlock_lock(monitored_spinlock_t *lock) {

struct timespec start, end;

clock_gettime(CLOCK_MONOTONIC, &start);

lock->stats.lock_attempts++;

while (atomic_flag_test_and_set(&lock->lock.locked)) {

lock->stats.lock_collisions++;

__asm__ volatile("pause" ::: "memory");

}

clock_gettime(CLOCK_MONOTONIC, &end);

double wait_time = (end.tv_sec - start.tv_sec) * 1e9 +

(end.tv_nsec - start.tv_nsec);

lock->stats.average_wait_time =

(lock->stats.average_wait_time * (lock->stats.lock_attempts - 1) +

wait_time) / lock->stats.lock_attempts;

}

In this example, the spinlock_t structure represents a basic spinlock, while the adaptive_spinlock_t structure represents a more advanced spinlock with exponential backoff. The monitored_spinlock_t structure includes performance monitoring capabilities, allowing developers to track lock contention and wait times.

3. RCU (Read-Copy-Update) Implementation

RCU is a synchronization mechanism that allows for highly concurrent read access with minimal overhead. It is particularly useful in scenarios where reads are much more frequent than writes, as it allows readers to proceed without blocking, even while updates are in progress.

Here’s an implementation of RCU in C:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <pthread.h>

#include <stdatomic.h>

typedef struct {

atomic_int readers;

pthread_mutex_t mutex;

} rcu_node_t;

typedef struct {

void *data;

atomic_int ref_count;

} rcu_data_t;

void rcu_init(rcu_node_t *rcu) {

atomic_init(&rcu->readers, 0);

pthread_mutex_init(&rcu->mutex, NULL);

}

void rcu_read_lock(rcu_node_t *rcu) {

atomic_fetch_add(&rcu->readers, 1);

__asm__ volatile("" ::: "memory"); // Memory barrier

}

void rcu_read_unlock(rcu_node_t *rcu) {

__asm__ volatile("" ::: "memory"); // Memory barrier

atomic_fetch_sub(&rcu->readers, 1);

}

void rcu_synchronize(rcu_node_t *rcu) {

pthread_mutex_lock(&rcu->mutex);

// Wait for all readers to complete

while (atomic_load(&rcu->readers) > 0) {

__asm__ volatile("pause" ::: "memory");

}

pthread_mutex_unlock(&rcu->mutex);

}

// Advanced RCU implementation with grace period detection

typedef struct {

atomic_int gp_count; // Grace period counter

atomic_int need_gp; // Grace period request flag

pthread_t gp_thread; // Grace period thread

bool shutdown;

} rcu_grace_period_t;

void *grace_period_thread(void *arg) {

rcu_grace_period_t *gp = (rcu_grace_period_t *)arg;

while (!gp->shutdown) {

if (atomic_load(&gp->need_gp)) {

// Start new grace period

atomic_fetch_add(&gp->gp_count, 1);

// Wait for readers

usleep(10000); // 10ms grace period

atomic_store(&gp->need_gp, 0);

}

usleep(1000); // 1ms sleep

}

return NULL;

}

// RCU linked list implementation

typedef struct rcu_list_node {

void *data;

struct rcu_list_node *next;

} rcu_list_node_t;

typedef struct {

rcu_list_node_t *head;

pthread_mutex_t mutex;

rcu_node_t rcu;

} rcu_list_t;

void rcu_list_init(rcu_list_t *list) {

list->head = NULL;

pthread_mutex_init(&list->mutex, NULL);

rcu_init(&list->rcu);

}

void rcu_list_insert(rcu_list_t *list, void *data) {

rcu_list_node_t *new_node = malloc(sizeof(rcu_list_node_t));

new_node->data = data;

pthread_mutex_lock(&list->mutex);

new_node->next = list->head;

list->head = new_node;

pthread_mutex_unlock(&list->mutex);

}

void rcu_list_delete(rcu_list_t *list, void *data) {

pthread_mutex_lock(&list->mutex);

rcu_list_node_t *curr = list->head;

rcu_list_node_t *prev = NULL;

while (curr != NULL) {

if (curr->data == data) {

if (prev == NULL) {

list->head = curr->next;

} else {

prev->next = curr->next;

}

// Schedule node deletion after grace period

rcu_synchronize(&list->rcu);

free(curr);

break;

}

prev = curr;

curr = curr->next;

}

pthread_mutex_unlock(&list->mutex);

}

In this example, the rcu_node_t structure represents an RCU node, while the rcu_data_t structure represents the data protected by RCU. The rcu_list_t structure represents an RCU-protected linked list, demonstrating how RCU can be used to manage concurrent access to data structures.

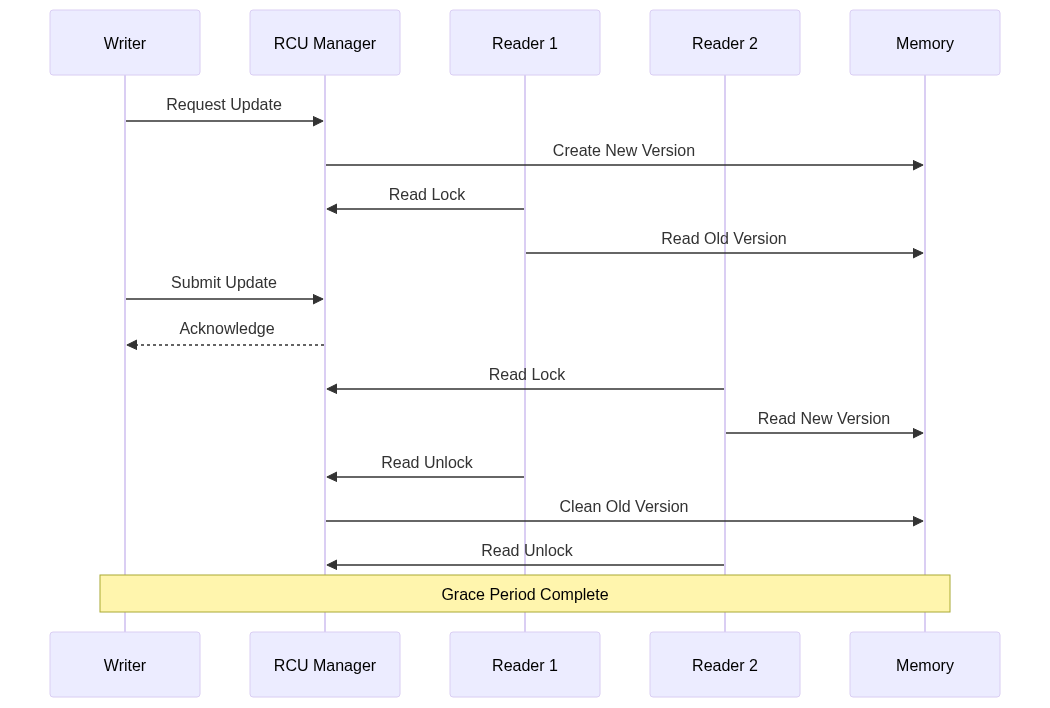

4. System Architecture

The system architecture for RCU typically involves several components, including writers, readers, and an RCU manager. These components work together to ensure that updates to shared data are performed safely and efficiently.

In this architecture, the RCU manager coordinates updates to shared data, ensuring that readers can continue to access the old version of the data while the update is in progress. Once all readers have finished accessing the old version, the RCU manager cleans it up, ensuring that memory is freed safely.

5. Performance Analysis

Key performance metrics for synchronization primitives:

-

Lock Contention: The amount of time spent waiting to acquire locks. High contention indicates potential bottlenecks in the system and may require redesign of the locking strategy.

-

Cache Line Bouncing: The effect of multiple cores attempting to access the same cache line, causing it to bounce between processor caches. This can significantly impact performance in spinlock implementations.

-

RCU Overhead: The additional memory and processing overhead required to maintain multiple versions of data structures and manage grace periods in RCU implementations.

These performance considerations are crucial for optimizing kernel code. By minimizing lock contention and cache line bouncing, developers can improve the performance of their spinlock implementations. Similarly, by carefully managing RCU overhead, developers can ensure that their RCU implementations are both efficient and scalable.

6. Debugging Tools

Debugging synchronization issues can be challenging, but there are tools and techniques that can help. Here’s an example of a debug-enabled spinlock implementation:

// Debug-enabled spinlock implementation

typedef struct {

atomic_flag locked;

const char *owner_file;

int owner_line;

pid_t owner_thread;

unsigned long lock_time;

} debug_spinlock_t;

#define LOCK_TIMEOUT_MS 1000

void debug_spinlock_lock(debug_spinlock_t *lock,

const char *file,

int line) {

unsigned long start_time = time(NULL);

while (atomic_flag_test_and_set(&lock->locked)) {

if (time(NULL) - start_time > LOCK_TIMEOUT_MS) {

fprintf(stderr, "Lock timeout at %s:%d\n", file, line);

fprintf(stderr, "Last acquired at %s:%d by thread %d\n",

lock->owner_file, lock->owner_line,

lock->owner_thread);

abort();

}

__asm__ volatile("pause" ::: "memory");

}

lock->owner_file = file;

lock->owner_line = line;

lock->owner_thread = pthread_self();

lock->lock_time = time(NULL);

}

#define DEBUG_LOCK(lock) \

debug_spinlock_lock(lock, __FILE__, __LINE__)

In this example, the debug_spinlock_t structure includes additional fields for tracking the owner of the lock and the time it was acquired. The DEBUG_LOCK macro is used to automatically capture the file and line number where the lock was acquired, making it easier to diagnose lock-related issues.

7. Best Practices

Critical considerations for synchronization primitive usage:

-

Lock Granularity: Choose the appropriate level of locking granularity to balance between concurrency and overhead. Fine-grained locking allows more parallelism but increases complexity and overhead.

-

RCU Usage Guidelines: Use RCU for read-mostly workloads where readers can tolerate accessing slightly stale data. Ensure proper grace period management to prevent memory leaks.

-

Error Handling: Implement robust error handling and timeout mechanisms to prevent deadlocks and detect lock acquisition failures early.

By following these best practices, developers can ensure that their synchronization primitives are both efficient and reliable, even in highly concurrent environments.

8. Conclusion

Understanding and properly implementing kernel synchronization primitives is crucial for developing efficient and reliable operating system components. Both spinlocks and RCU serve different purposes and should be chosen based on specific use cases and performance requirements. By leveraging these synchronization mechanisms, developers can ensure that their kernel code is both performant and free from race conditions, even in highly concurrent environments.