Can I Make My Code Run Faster? Implementing Multithreading And Process Management

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Core Concepts: Processes vs Threads

- Implementation Deep Dive

- Thread Pool Implementation

- Thread Safety and Synchronization

- Performance Considerations

- Best Practices

- Further Reading

- Conclusion

Introduction

In modern computing, understanding the distinction between processes and threads, along with their optimal use cases, is crucial for developing efficient and scalable applications. This article explains the technical aspects of processes and threads, their implementation details, and practical applications in system programming.

Core Concepts: Processes vs Threads

Process Architecture

A process represents a program in execution - the transformation of static code into a dynamic entity. When examining process architecture, several key components come into play:

- Virtual Memory Space:

- Each process receives its own isolated virtual address space

- Typically ranges from 0 to 2^48-1 on modern 64-bit systems

- Divided into segments: text (code), data, heap, and stack

- Process Control Block (PCB):

- Contains essential process metadata

- Stores:

- Process ID (PID)

- Program counter (PC)

- Register contents

- Memory management information

- Scheduling information

- I/O status information

- Resource Ownership:

- File descriptors

- Network sockets

- Memory mappings

- System V IPC structures

Thread Architecture

Threads represent lightweight execution units within a process. Their architecture differs significantly from processes:

- Shared Resources:

- Code segment

- Data segment

- Open file descriptors

- Signals and signal handlers

- Current working directory

- Thread-Specific Elements:

- Stack pointer

- Program counter

- Register set

- Thread ID (TID)

- Signal mask

- errno variable

- Thread-specific data

- Thread Control Block (TCB):

- Lighter than PCB

- Contains:

- Thread identifier

- Stack pointer

- Program counter

- Thread state

- CPU register contents

Implementation Deep Dive

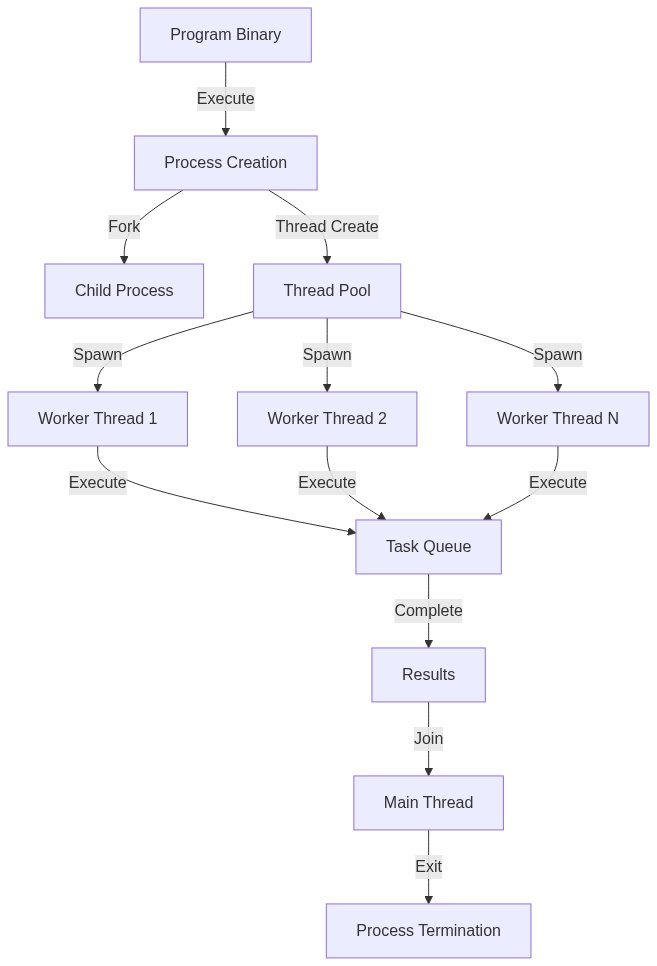

Process Creation

The process creation mechanism involves several complex steps at the kernel level:

- Memory Space Initialization:

void *stack = mmap(NULL, STACK_SIZE, PROT_READ | PROT_WRITE, MAP_PRIVATE | MAP_ANONYMOUS | MAP_STACK, -1, 0); - File Descriptor Table:

- Copying or creating new file descriptors

- Setting up standard streams (stdin, stdout, stderr)

- Process Credentials:

- User ID (UID)

- Group ID (GID)

- Supplementary groups

Here’s a complete implementation demonstrating process creation:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <sys/wait.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

int main() {

pid_t pid = fork();

if (pid < 0) {

perror("Fork failed");

exit(1);

}

if (pid == 0) {

// Child process

printf("Child process (PID: %d)\n", getpid());

printf("Parent PID: %d\n", getppid());

// Demonstrate virtual memory isolation

int *ptr = malloc(sizeof(int));

*ptr = 42;

printf("Child memory address: %p, value: %d\n",

(void*)ptr, *ptr);

free(ptr);

exit(0);

} else {

// Parent process

printf("Parent process (PID: %d)\n", getpid());

// Demonstrate separate memory space

int *ptr = malloc(sizeof(int));

*ptr = 100;

printf("Parent memory address: %p, value: %d\n",

(void*)ptr, *ptr);

// Wait for child to complete

int status;

waitpid(pid, &status, 0);

free(ptr);

}

return 0;

}

To compile and run:

gcc -o process_demo process_demo.c

./process_demo

Expected output:

Parent process (PID: 1234)

Parent memory address: 0x55555576b2a0, value: 100

Child process (PID: 1235)

Parent PID: 1234

Child memory address: 0x55555576b2a0, value: 42

Key assembly instructions (x86_64):

; Process creation (fork)

mov rax, 57 ; sys_fork system call number

syscall ; Execute system call

; Memory allocation

mov edi, 4 ; Size argument for malloc

call malloc ; Call malloc function

Thread Implementation

Thread creation involves different mechanisms than process creation. Here’s a detailed implementation showcasing thread creation and synchronization:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <pthread.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#define NUM_THREADS 4

#define ITERATIONS 1000000

// Shared resource

long shared_counter = 0;

pthread_mutex_t mutex = PTHREAD_MUTEX_INITIALIZER;

void* thread_function(void* arg) {

int thread_id = *(int*)arg;

for (int i = 0; i < ITERATIONS; i++) {

pthread_mutex_lock(&mutex);

shared_counter++;

pthread_mutex_unlock(&mutex);

}

printf("Thread %d completed\n", thread_id);

return NULL;

}

int main() {

pthread_t threads[NUM_THREADS];

int thread_ids[NUM_THREADS];

// Create threads

for (int i = 0; i < NUM_THREADS; i++) {

thread_ids[i] = i;

if (pthread_create(&threads[i], NULL,

thread_function,

&thread_ids[i]) != 0) {

perror("Thread creation failed");

exit(1);

}

}

// Wait for threads to complete

for (int i = 0; i < NUM_THREADS; i++) {

pthread_join(threads[i], NULL);

}

printf("Final counter value: %ld\n", shared_counter);

pthread_mutex_destroy(&mutex);

return 0;

}

To compile and run:

gcc -o thread_demo thread_demo.c -pthread

./thread_demo

Expected output:

Thread 2 completed

Thread 0 completed

Thread 3 completed

Thread 1 completed

Final counter value: 4000000

Thread Pool Implementation

A thread pool is an essential pattern for managing thread lifecycle and task execution. Here’s a complete implementation:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <pthread.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#define POOL_SIZE 4

#define QUEUE_SIZE 1000

typedef struct {

void (*function)(void*);

void* argument;

} task_t;

typedef struct {

task_t* tasks;

int front;

int rear;

int count;

int size;

pthread_mutex_t mutex;

pthread_cond_t not_empty;

pthread_cond_t not_full;

int shutdown;

} task_queue_t;

typedef struct {

pthread_t* threads;

task_queue_t* queue;

int thread_count;

} thread_pool_t;

// Task queue operations

void task_queue_init(task_queue_t* queue, int size) {

queue->tasks = malloc(sizeof(task_t) * size);

queue->size = size;

queue->front = queue->rear = queue->count = 0;

queue->shutdown = 0;

pthread_mutex_init(&queue->mutex, NULL);

pthread_cond_init(&queue->not_empty, NULL);

pthread_cond_init(&queue->not_full, NULL);

}

int task_queue_push(task_queue_t* queue, task_t task) {

pthread_mutex_lock(&queue->mutex);

while (queue->count == queue->size && !queue->shutdown) {

pthread_cond_wait(&queue->not_full, &queue->mutex);

}

if (queue->shutdown) {

pthread_mutex_unlock(&queue->mutex);

return -1;

}

queue->tasks[queue->rear] = task;

queue->rear = (queue->rear + 1) % queue->size;

queue->count++;

pthread_cond_signal(&queue->not_empty);

pthread_mutex_unlock(&queue->mutex);

return 0;

}

int task_queue_pop(task_queue_t* queue, task_t* task) {

pthread_mutex_lock(&queue->mutex);

while (queue->count == 0 && !queue->shutdown) {

pthread_cond_wait(&queue->not_empty, &queue->mutex);

}

if (queue->shutdown && queue->count == 0) {

pthread_mutex_unlock(&queue->mutex);

return -1;

}

*task = queue->tasks[queue->front];

queue->front = (queue->front + 1) % queue->size;

queue->count--;

pthread_cond_signal(&queue->not_full);

pthread_mutex_unlock(&queue->mutex);

return 0;

}

// Thread pool worker function

void* worker(void* arg) {

thread_pool_t* pool = (thread_pool_t*)arg;

task_t task;

while (1) {

if (task_queue_pop(pool->queue, &task) < 0) {

break;

}

(task.function)(task.argument);

}

return NULL;

}

// Thread pool operations

thread_pool_t* thread_pool_create(int thread_count) {

thread_pool_t* pool = malloc(sizeof(thread_pool_t));

pool->thread_count = thread_count;

pool->threads = malloc(sizeof(pthread_t) * thread_count);

pool->queue = malloc(sizeof(task_queue_t));

task_queue_init(pool->queue, QUEUE_SIZE);

for (int i = 0; i < thread_count; i++) {

pthread_create(&pool->threads[i], NULL, worker, pool);

}

return pool;

}

void thread_pool_destroy(thread_pool_t* pool) {

pool->queue->shutdown = 1;

pthread_cond_broadcast(&pool->queue->not_empty);

for (int i = 0; i < pool->thread_count; i++) {

pthread_join(pool->threads[i], NULL);

}

free(pool->queue->tasks);

free(pool->queue);

free(pool->threads);

free(pool);

}

// Example usage

void example_task(void* arg) {

int id = *(int*)arg;

printf("Task %d executing\n", id);

usleep(100000); // Simulate work

}

int main() {

thread_pool_t* pool = thread_pool_create(POOL_SIZE);

int* task_ids = malloc(sizeof(int) * 20);

// Submit tasks

for (int i = 0; i < 20; i++) {

task_ids[i] = i;

task_t task = {example_task, &task_ids[i]};

task_queue_push(pool->queue, task);

}

sleep(3); // Allow tasks to complete

thread_pool_destroy(pool);

free(task_ids);

return 0;

}

Thread Safety and Synchronization

Thread safety is crucial when working with shared resources. Key concepts include:

- Mutex Operations:

- Lock acquisition

- Lock release

- Deadlock prevention

- Priority inheritance

- Condition Variables:

- Signal/broadcast mechanisms

- Waiting on conditions

- Spurious wakeups

- Memory Barriers:

- Read barriers

- Write barriers

- Full memory fences

Performance Considerations

When implementing threaded applications, consider:

- Context Switching Overhead:

- CPU cache effects

- TLB flush costs

- Register save/restore

- Memory Access Patterns:

- False sharing

- Cache line bouncing

- Memory ordering

- Thread Pool Sizing:

- CPU core count

- I/O vs CPU bound tasks

- Work queue depth

Best Practices

- Thread Creation:

- Use thread pools for recurring tasks

- Limit thread count to CPU cores * 2

- Consider thread stack size

- Synchronization:

- Use the smallest possible critical sections

- Prefer reader-writer locks for read-heavy workloads

- Implement proper error handling

- Resource Management:

- Clean up thread-local storage

- Properly destroy synchronization primitives

- Handle thread cancellation points

Further Reading

For more detailed information on specific topics:

- POSIX Threads Programming Guide

- Linux System Programming (O’Reilly)

- Understanding the Linux Kernel

- Advanced Programming in the UNIX Environment

Conclusion

Understanding threads and processes is fundamental to systems programming. While threads offer advantages in terms of resource sharing and context switching overhead, they come with complexities in terms of synchronization and debugging. Careful consideration of use cases and proper implementation of thread safety mechanisms is crucial for building reliable multi-threaded applications. The code examples provided demonstrate practical implementations of these concepts, while the theoretical discussion provides the necessary foundation for understanding their behavior and optimal usage patterns.