Everything You Need To Know About Postgresql Locks: Practical Skills You Need

PostgreSQL is a powerful database system that uses special locking methods to keep data safe and allow many users to work with it at the same time. Knowing how these locks work is really important for people who manage databases or build apps, especially if they want their systems to run fast and smooth. This post clearly explains PostgreSQL’s locking system and gives simple SQL commands you can use to check and see each lock working for yourself.

Table of Contents

- Introduction to Locking in PostgreSQL

- Lock Levels in PostgreSQL

- Setting Up a Test Environment

- Observing Locks in PostgreSQL

- Table-Level Locks in PostgreSQL

- Lock Conflicts Matrix

- Testing Lock Conflicts

- Row-Level Locks in PostgreSQL

- Row Lock Conflict Matrix

- Detecting and Resolving Deadlocks

- Page-Level Locks

- Advisory Locks

- PostgreSQL Lock Types Comparison

- Practical Applications of Locking Knowledge

- Impact of Lock Modes on Common Operations

- Best Practices for Handling Locks

- Conclusion

Introduction to Locking in PostgreSQL

Locks in PostgreSQL are essential for concurrency control—they prevent multiple sessions from making conflicting changes to the same data. When we talk about locks, we typically think of them in two categories: shared locks (reader locks) and exclusive locks (writer locks). However, PostgreSQL implements a more nuanced approach with various lock modes at different levels.

Understanding these mechanisms helps in:

- Diagnosing performance issues

- Preventing deadlocks

- Designing applications that scale well under high concurrency

- Ensuring data integrity without sacrificing performance

Let’s explore the different lock levels and their impact on database operations.

Lock Levels in PostgreSQL

PostgreSQL implements locking at three primary levels:

- Table-level locks - Affect entire tables

- Row-level locks - Target specific rows

- Page-level locks - Operate on individual data pages (8KB blocks)

Additionally, PostgreSQL provides advisory locks, which are application-defined locks that don’t correspond to any database object.

Let’s start by setting up our test environment.

Setting Up a Test Environment

First, let’s create a simple database and table to demonstrate locking behavior:

-- Create test database

CREATE DATABASE lock_test;

\c lock_test

-- Create test table

CREATE TABLE accounts (

account_id SERIAL PRIMARY KEY,

account_number VARCHAR(20) UNIQUE,

balance NUMERIC(15,2) NOT NULL,

last_updated TIMESTAMP DEFAULT CURRENT_TIMESTAMP

);

-- Insert sample data

INSERT INTO accounts (account_number, balance)

VALUES

('ACC-1001', 5000.00),

('ACC-1002', 7500.00),

('ACC-1003', 12000.00),

('ACC-1004', 3200.00),

('ACC-1005', 9800.00);

Observing Locks in PostgreSQL

PostgreSQL provides several system views to monitor locks:

pg_locks- Shows all active locks in the systempg_stat_activity- Shows information about current sessions

Let’s create a helper query to observe locks more easily:

-- Create a view to easily see locks with more context

CREATE OR REPLACE VIEW lock_monitor AS

SELECT

l.locktype,

l.relation::regclass AS table_name,

l.page,

l.tuple,

l.virtualxid,

l.transactionid::text,

l.classid,

l.objid,

l.objsubid,

l.mode,

l.granted,

a.application_name,

a.query,

a.pid,

a.usename,

a.client_addr,

a.state,

a.state_change,

a.xact_start

FROM pg_locks l

JOIN pg_stat_activity a ON l.pid = a.pid

WHERE l.pid <> pg_backend_pid() -- Exclude the current session

ORDER BY l.pid, l.relation, l.page, l.tuple;

Now let’s explore each lock type one by one, with practical examples.

Table-Level Locks in PostgreSQL

Table-level locks affect an entire table and come in various modes, each with different behaviors.

Here are the main table-level lock modes in order of increasing exclusivity:

1. ACCESS SHARE Lock

This is the least restrictive lock, acquired by SELECT operations. It only conflicts with ACCESS EXCLUSIVE locks.

Test in terminal 1:

BEGIN;

SELECT * FROM accounts;

-- Keep transaction open

In terminal 2, check the locks:

SELECT * FROM lock_monitor WHERE table_name = 'accounts';

You should see an AccessShareLock on the accounts table.

2. ROW SHARE Lock

Acquired by SELECT FOR UPDATE, SELECT FOR SHARE, etc. Let’s see it in action:

Terminal 1:

BEGIN;

SELECT * FROM accounts WHERE account_id = 1 FOR UPDATE;

-- Keep transaction open

Terminal 2:

SELECT * FROM lock_monitor WHERE table_name = 'accounts';

You should see both AccessShareLock and RowShareLock on the accounts table.

3. ROW EXCLUSIVE Lock

This is acquired by UPDATE, INSERT, and DELETE operations.

Terminal 1:

BEGIN;

UPDATE accounts SET balance = balance + 100 WHERE account_id = 2;

-- Keep transaction open

Terminal 2:

SELECT * FROM lock_monitor WHERE table_name = 'accounts';

You should see a RowExclusiveLock on the accounts table.

4. SHARE UPDATE EXCLUSIVE Lock

This lock is acquired by VACUUM, ANALYZE, and CREATE INDEX CONCURRENTLY.

Terminal 1:

BEGIN;

ANALYZE accounts;

-- Keep transaction open

Terminal 2:

SELECT * FROM lock_monitor WHERE table_name = 'accounts';

You should see a ShareUpdateExclusiveLock.

5. SHARE Lock

This lock is acquired by CREATE INDEX (non-concurrent).

Terminal 1:

BEGIN;

CREATE INDEX test_index ON accounts(balance);

-- This will hold the lock until committed or rolled back

Terminal 2:

SELECT * FROM lock_monitor WHERE table_name = 'accounts';

You should see a ShareLock on the accounts table.

6. SHARE ROW EXCLUSIVE Lock

This lock is acquired by CREATE TRIGGER and some forms of ALTER TABLE.

Terminal 1:

BEGIN;

CREATE TRIGGER update_timestamp

BEFORE UPDATE ON accounts

FOR EACH ROW EXECUTE FUNCTION trigger_set_timestamp();

-- Keep transaction open

First, let’s create the needed function:

CREATE OR REPLACE FUNCTION trigger_set_timestamp()

RETURNS TRIGGER AS $$

BEGIN

NEW.last_updated = NOW();

RETURN NEW;

END;

$$ LANGUAGE plpgsql;

Terminal 2:

SELECT * FROM lock_monitor WHERE table_name = 'accounts';

You should see a ShareRowExclusiveLock.

7. EXCLUSIVE Lock

This lock is acquired by REFRESH MATERIALIZED VIEW CONCURRENTLY.

Let’s create a materialized view first:

CREATE MATERIALIZED VIEW account_summary AS

SELECT count(*) as total_accounts, sum(balance) as total_balance

FROM accounts;

Terminal 1:

BEGIN;

REFRESH MATERIALIZED VIEW CONCURRENTLY account_summary;

-- Keep transaction open

Terminal 2:

SELECT * FROM lock_monitor WHERE table_name IN ('accounts', 'account_summary');

8. ACCESS EXCLUSIVE Lock

This is the most restrictive lock, acquired by DROP TABLE, TRUNCATE, VACUUM FULL, REINDEX, CLUSTER, etc.

Terminal 1:

BEGIN;

TRUNCATE accounts;

-- Keep transaction open

Terminal 2:

SELECT * FROM lock_monitor WHERE table_name = 'accounts';

You should see an AccessExclusiveLock on the accounts table.

Lock Conflicts Matrix

Here’s a table that shows which lock modes conflict with each other:

-- Create a temporary table to demonstrate lock conflicts

CREATE TEMP TABLE lock_conflicts (

requesting_lock text,

existing_locks text[]

);

INSERT INTO lock_conflicts VALUES

('ACCESS SHARE', ARRAY['ACCESS EXCLUSIVE']),

('ROW SHARE', ARRAY['EXCLUSIVE', 'ACCESS EXCLUSIVE']),

('ROW EXCLUSIVE', ARRAY['SHARE', 'SHARE ROW EXCLUSIVE', 'EXCLUSIVE', 'ACCESS EXCLUSIVE']),

('SHARE UPDATE EXCLUSIVE', ARRAY['SHARE UPDATE EXCLUSIVE', 'SHARE', 'SHARE ROW EXCLUSIVE', 'EXCLUSIVE', 'ACCESS EXCLUSIVE']),

('SHARE', ARRAY['ROW EXCLUSIVE', 'SHARE UPDATE EXCLUSIVE', 'SHARE ROW EXCLUSIVE', 'EXCLUSIVE', 'ACCESS EXCLUSIVE']),

('SHARE ROW EXCLUSIVE', ARRAY['ROW EXCLUSIVE', 'SHARE UPDATE EXCLUSIVE', 'SHARE', 'SHARE ROW EXCLUSIVE', 'EXCLUSIVE', 'ACCESS EXCLUSIVE']),

('EXCLUSIVE', ARRAY['ROW SHARE', 'ROW EXCLUSIVE', 'SHARE UPDATE EXCLUSIVE', 'SHARE', 'SHARE ROW EXCLUSIVE', 'EXCLUSIVE', 'ACCESS EXCLUSIVE']),

('ACCESS EXCLUSIVE', ARRAY['ACCESS SHARE', 'ROW SHARE', 'ROW EXCLUSIVE', 'SHARE UPDATE EXCLUSIVE', 'SHARE', 'SHARE ROW EXCLUSIVE', 'EXCLUSIVE', 'ACCESS EXCLUSIVE']);

-- Query to display the conflicts

SELECT

requesting_lock,

string_agg(el, ', ') AS conflicts_with

FROM lock_conflicts, unnest(existing_locks) el

GROUP BY requesting_lock

ORDER BY requesting_lock;

Testing Lock Conflicts

Let’s test some common lock conflicts to see how they behave.

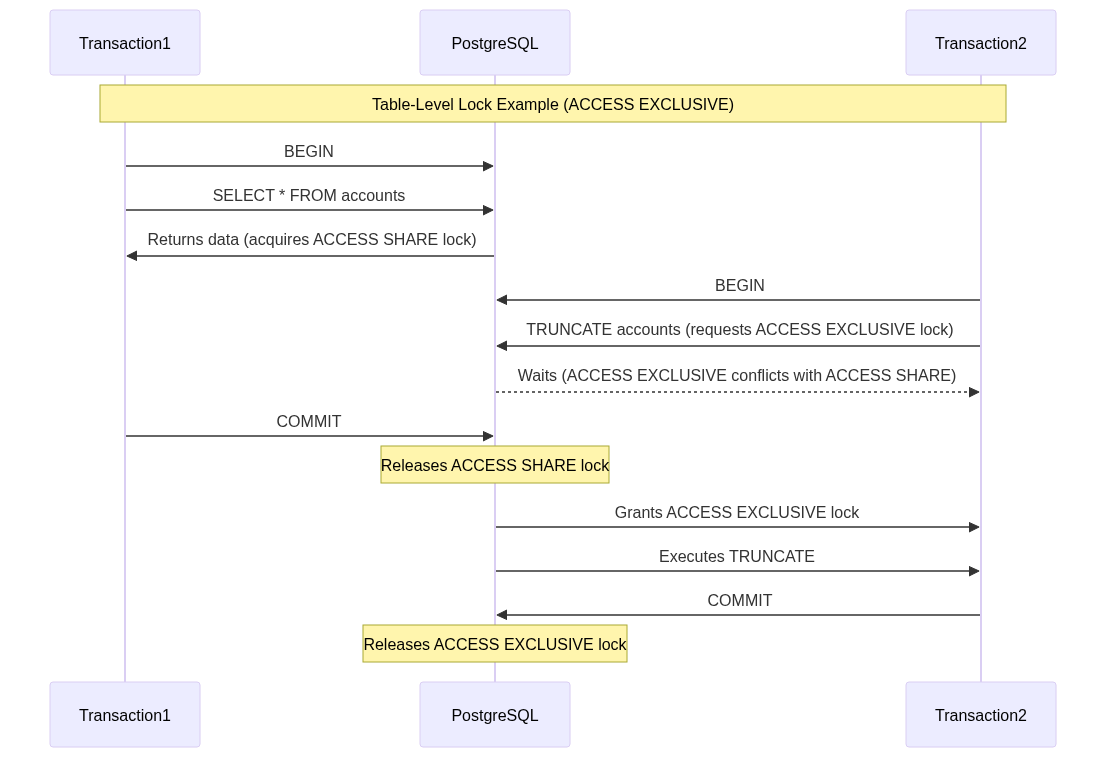

Testing ACCESS EXCLUSIVE vs ACCESS SHARE

Terminal 1:

BEGIN;

SELECT * FROM accounts; -- Acquire ACCESS SHARE

-- Keep transaction open

Terminal 2:

BEGIN;

TRUNCATE accounts; -- Try to acquire ACCESS EXCLUSIVE

-- This will wait

Terminal 3:

SELECT a.pid,

a.usename,

a.query,

a.state,

l.mode,

l.granted

FROM pg_stat_activity a

JOIN pg_locks l ON a.pid = l.pid

WHERE relation = 'accounts'::regclass::oid

ORDER BY l.granted DESC;

You should see that the TRUNCATE command in Terminal 2 is waiting for the ACCESS SHARE lock to be released.

Testing ROW EXCLUSIVE vs SHARE

Terminal 1:

BEGIN;

UPDATE accounts SET balance = balance + 200 WHERE account_id = 3; -- Acquire ROW EXCLUSIVE

-- Keep transaction open

Terminal 2:

BEGIN;

CREATE INDEX balance_idx ON accounts(balance); -- Try to acquire SHARE

-- This will wait

Terminal 3:

SELECT a.pid,

a.usename,

a.query,

a.state,

l.mode,

l.granted

FROM pg_stat_activity a

JOIN pg_locks l ON a.pid = l.pid

WHERE relation = 'accounts'::regclass::oid

ORDER BY l.granted DESC;

Row-Level Locks in PostgreSQL

Row-level locks in PostgreSQL are used to control access to individual rows. They come in four modes:

- FOR UPDATE - Most restrictive, blocks any operation that would modify the locked row

- FOR NO KEY UPDATE - Similar to FOR UPDATE but doesn’t block FOR KEY SHARE

- FOR SHARE - Allows concurrent FOR SHARE but blocks modifications

- FOR KEY SHARE - Least restrictive, only blocks key modifications

Let’s test each one:

FOR UPDATE Lock

Terminal 1:

BEGIN;

SELECT * FROM accounts WHERE account_id = 1 FOR UPDATE;

-- Keep transaction open

Terminal 2:

BEGIN;

UPDATE accounts SET balance = balance + 300 WHERE account_id = 1;

-- This will wait

Terminal 3:

SELECT a.pid,

a.usename,

a.query,

a.state,

l.mode,

l.granted

FROM pg_stat_activity a

JOIN pg_locks l ON a.pid = l.pid

WHERE relation = 'accounts'::regclass::oid

ORDER BY l.granted DESC;

FOR NO KEY UPDATE Lock

Terminal 1:

BEGIN;

SELECT * FROM accounts WHERE account_id = 2 FOR NO KEY UPDATE;

-- Keep transaction open

Terminal 2:

BEGIN;

SELECT * FROM accounts WHERE account_id = 2 FOR KEY SHARE;

-- This should not wait

Terminal 3:

BEGIN;

UPDATE accounts SET balance = balance + 400 WHERE account_id = 2;

-- This will wait

FOR SHARE Lock

Terminal 1:

BEGIN;

SELECT * FROM accounts WHERE account_id = 3 FOR SHARE;

-- Keep transaction open

Terminal 2:

BEGIN;

SELECT * FROM accounts WHERE account_id = 3 FOR SHARE;

-- This should not wait

Terminal 3:

BEGIN;

UPDATE accounts SET balance = balance + 500 WHERE account_id = 3;

-- This will wait

FOR KEY SHARE Lock

Terminal 1:

BEGIN;

SELECT * FROM accounts WHERE account_id = 4 FOR KEY SHARE;

-- Keep transaction open

Terminal 2:

BEGIN;

UPDATE accounts SET balance = balance + 600 WHERE account_id = 4;

-- This will wait since it affects a key column

Terminal 3:

BEGIN;

UPDATE accounts SET last_updated = NOW() WHERE account_id = 4;

-- This should proceed if last_updated isn't part of any key

Row Lock Conflict Matrix

Similar to table locks, row locks also have a conflict matrix:

-- Create a temporary table to demonstrate row lock conflicts

CREATE TEMP TABLE row_lock_conflicts (

requesting_lock text,

existing_locks text[]

);

INSERT INTO row_lock_conflicts VALUES

('FOR KEY SHARE', ARRAY['FOR UPDATE']),

('FOR SHARE', ARRAY['FOR UPDATE', 'FOR NO KEY UPDATE']),

('FOR NO KEY UPDATE', ARRAY['FOR UPDATE', 'FOR NO KEY UPDATE', 'FOR SHARE']),

('FOR UPDATE', ARRAY['FOR UPDATE', 'FOR NO KEY UPDATE', 'FOR SHARE', 'FOR KEY SHARE']);

-- Query to display the conflicts

SELECT

requesting_lock,

string_agg(el, ', ') AS conflicts_with

FROM row_lock_conflicts, unnest(existing_locks) el

GROUP BY requesting_lock

ORDER BY requesting_lock;

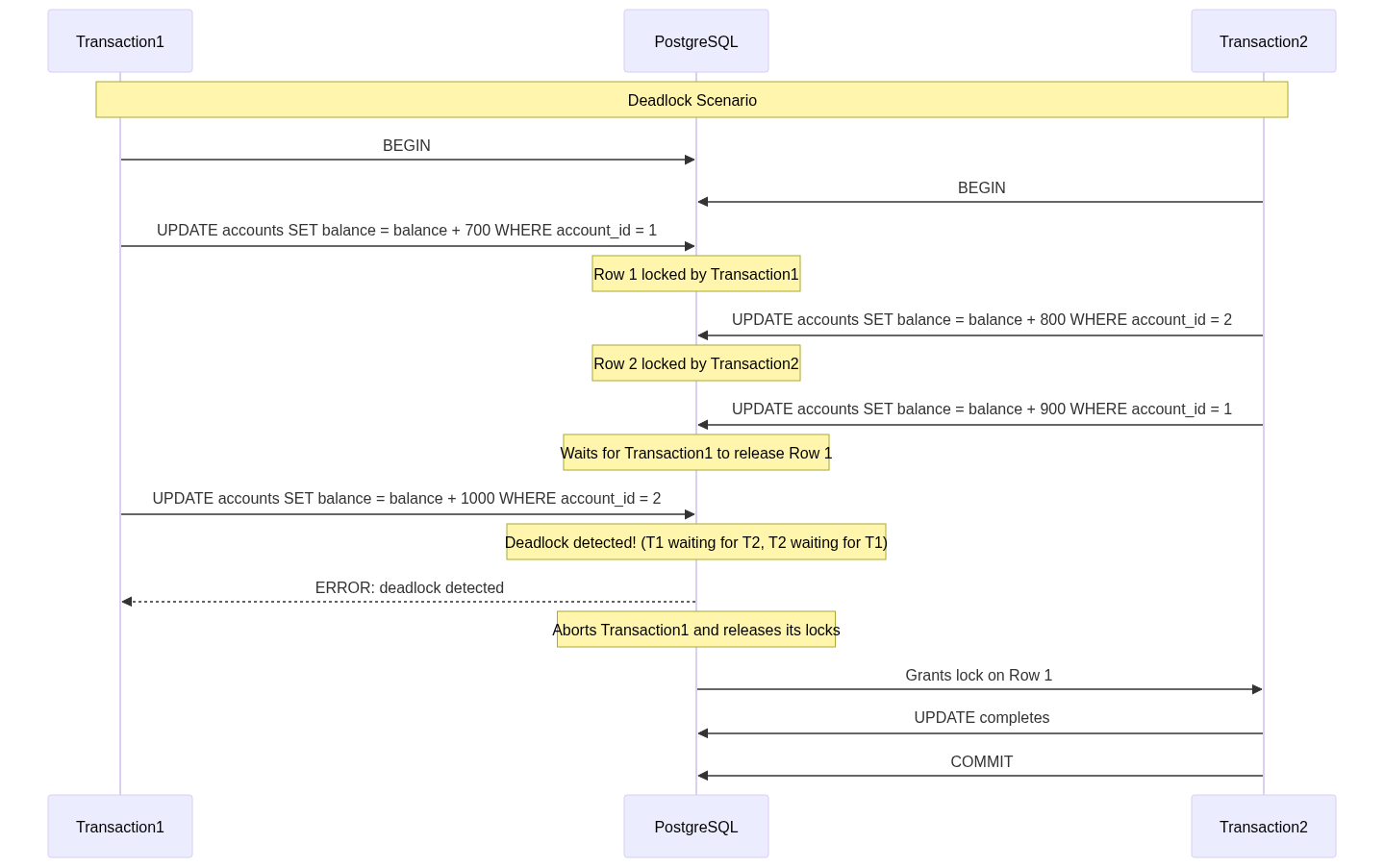

Detecting and Resolving Deadlocks

Deadlocks occur when two or more transactions are waiting for each other to release locks. PostgreSQL automatically detects deadlocks and resolves them by aborting one of the transactions.

Let’s create a deadlock scenario:

Terminal 1:

BEGIN;

UPDATE accounts SET balance = balance + 700 WHERE account_id = 1;

-- Keep transaction open

Terminal 2:

BEGIN;

UPDATE accounts SET balance = balance + 800 WHERE account_id = 2;

-- Keep transaction open

-- Now try to update account_id = 1, which Terminal 1 has locked

UPDATE accounts SET balance = balance + 900 WHERE account_id = 1;

-- This will wait

Terminal 1 (continuing):

-- Now try to update account_id = 2, which Terminal 2 has locked

UPDATE accounts SET balance = balance + 1000 WHERE account_id = 2;

-- This will cause a deadlock

PostgreSQL will detect the deadlock and one of the transactions will be automatically aborted with an error message.

Page-Level Locks

Page-level locks in PostgreSQL are used to control access to shared buffer pool pages. These are typically short-lived and are released immediately after a row is fetched or updated.

Unfortunately, page-level locks are not exposed through PostgreSQL’s system views, so we can’t directly observe them. However, they exist internally and play a crucial role in maintaining data consistency.

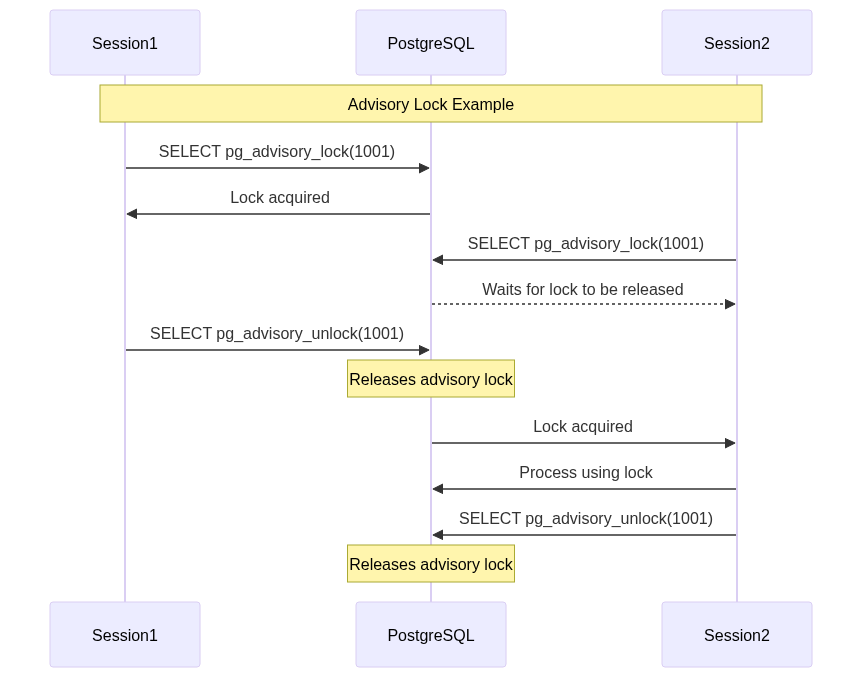

Advisory Locks

Advisory locks are a unique feature in PostgreSQL that allows applications to create locks that have application-defined meaning. They’re not tied to any database object and must be managed correctly by the application.

There are two types of advisory locks:

- Session-level advisory locks - Held until explicitly released or the session ends

- Transaction-level advisory locks - Released automatically at the end of the transaction

Let’s test both types:

Session-Level Advisory Lock

Terminal 1:

-- Acquire a session-level advisory lock with ID 1001

SELECT pg_advisory_lock(1001);

-- Keep session open

Terminal 2:

-- Try to acquire the same lock

SELECT pg_advisory_lock(1001);

-- This will wait

Terminal 3:

-- Check lock status

SELECT * FROM pg_locks WHERE locktype = 'advisory';

Terminal 1 (continuing):

-- Release the lock

SELECT pg_advisory_unlock(1001);

Terminal 2 should now acquire the lock.

Transaction-Level Advisory Lock

Terminal 1:

BEGIN;

-- Acquire a transaction-level advisory lock with ID 2001

SELECT pg_advisory_xact_lock(2001);

-- Keep transaction open

Terminal 2:

BEGIN;

-- Try to acquire the same lock

SELECT pg_advisory_xact_lock(2001);

-- This will wait

Terminal 1 (continuing):

-- Commit the transaction (this will release the lock)

COMMIT;

Terminal 2 should now acquire the lock.

PostgreSQL Lock Types Comparison

Table-Level Locks

| Lock Mode | Acquired By | Conflicts With | Purpose | Blocking Behavior |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACCESS SHARE | SELECT |

ACCESS EXCLUSIVE | Protects table from being dropped while reading | Least restrictive, only blocks schema changes |

| ROW SHARE | SELECT FOR UPDATE/SHARE |

EXCLUSIVE, ACCESS EXCLUSIVE | Protects rows being modified from concurrent schema changes | Allows most concurrent operations except some schema changes |

| ROW EXCLUSIVE | UPDATE, DELETE, INSERT |

SHARE, SHARE ROW EXCLUSIVE, EXCLUSIVE, ACCESS EXCLUSIVE | Protects table for write operations | Allows concurrent data modifications but blocks schema changes |

| SHARE UPDATE EXCLUSIVE | VACUUM, ANALYZE, CREATE INDEX CONCURRENTLY |

SHARE UPDATE EXCLUSIVE, SHARE, SHARE ROW EXCLUSIVE, EXCLUSIVE, ACCESS EXCLUSIVE | Protects against concurrent schema changes and VACUUM | Allows concurrent reads and writes |

| SHARE | CREATE INDEX |

ROW EXCLUSIVE, SHARE UPDATE EXCLUSIVE, SHARE ROW EXCLUSIVE, EXCLUSIVE, ACCESS EXCLUSIVE | Protects table from concurrent modifications during index creation | Blocks data modification but allows reads |

| SHARE ROW EXCLUSIVE | CREATE TRIGGER, some forms of ALTER TABLE |

ROW EXCLUSIVE, SHARE UPDATE EXCLUSIVE, SHARE, SHARE ROW EXCLUSIVE, EXCLUSIVE, ACCESS EXCLUSIVE | Protects table from concurrent data modifications and reads | More restrictive than SHARE |

| EXCLUSIVE | REFRESH MATERIALIZED VIEW CONCURRENTLY |

ROW SHARE, ROW EXCLUSIVE, SHARE UPDATE EXCLUSIVE, SHARE, SHARE ROW EXCLUSIVE, EXCLUSIVE, ACCESS EXCLUSIVE | Allows only reads from the table | Blocks most operations except simple SELECT |

| ACCESS EXCLUSIVE | DROP TABLE, TRUNCATE, VACUUM FULL, REINDEX, CLUSTER |

ALL LOCK TYPES | Complete control over the table | Most restrictive, blocks all concurrent access |

Row-Level Locks

| Lock Mode | Acquired By | Conflicts With | Purpose | Blocking Behavior |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FOR KEY SHARE | SELECT FOR KEY SHARE |

FOR UPDATE | Protects rows from having their key values modified | Least restrictive, blocks only key modifications |

| FOR SHARE | SELECT FOR SHARE |

FOR UPDATE, FOR NO KEY UPDATE | Protects rows from modification | Allows concurrent FOR SHARE but blocks modifications |

| FOR NO KEY UPDATE | UPDATE (non-key columns) |

FOR UPDATE, FOR NO KEY UPDATE, FOR SHARE | Protects rows from modification except key shares | More restrictive than FOR KEY SHARE |

| FOR UPDATE | SELECT FOR UPDATE, UPDATE |

ALL ROW LOCK TYPES | Full control over the row | Most restrictive, blocks any operation on the row |

Advisory Locks

| Lock Type | Acquired By | Scope | Release Mechanism | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Session-level | pg_advisory_lock() |

Database session | pg_advisory_unlock() or session end |

Application-defined locks, held until explicitly released |

| Transaction-level | pg_advisory_xact_lock() |

Transaction | Automatic at transaction end | Application-defined locks, automatically released at transaction end |

Practical Applications of Locking Knowledge

Understanding PostgreSQL’s locking mechanisms is invaluable for several practical applications:

1. Optimizing VACUUM operations

VACUUM is crucial for PostgreSQL’s performance, as it reclaims space and updates visibility information. Understanding that VACUUM (without FULL) acquires only a SHARE UPDATE EXCLUSIVE lock means it can run concurrently with most operations except schema changes and other VACUUM operations.

-- Check if VACUUM is blocked

SELECT blocked_activity.pid AS blocked_pid,

blocked_activity.query AS blocked_query,

blocking_activity.pid AS blocking_pid,

blocking_activity.query AS blocking_query

FROM pg_catalog.pg_locks AS blocked_locks

JOIN pg_catalog.pg_stat_activity AS blocked_activity ON blocked_activity.pid = blocked_locks.pid

JOIN pg_catalog.pg_locks AS blocking_locks ON blocking_locks.locktype = blocked_locks.locktype

AND blocking_locks.database IS NOT DISTINCT FROM blocked_locks.database

AND blocking_locks.relation IS NOT DISTINCT FROM blocked_locks.relation

AND blocking_locks.page IS NOT DISTINCT FROM blocked_locks.page

AND blocking_locks.tuple IS NOT DISTINCT FROM blocked_locks.tuple

AND blocking_locks.virtualxid IS NOT DISTINCT FROM blocked_locks.virtualxid

AND blocking_locks.transactionid IS NOT DISTINCT FROM blocked_locks.transactionid

AND blocking_locks.classid IS NOT DISTINCT FROM blocked_locks.classid

AND blocking_locks.objid IS NOT DISTINCT FROM blocked_locks.objid

AND blocking_locks.objsubid IS NOT DISTINCT FROM blocked_locks.objsubid

AND blocking_locks.pid != blocked_locks.pid

JOIN pg_catalog.pg_stat_activity AS blocking_activity ON blocking_activity.pid = blocking_locks.pid

WHERE NOT blocked_locks.granted

AND blocked_activity.query LIKE '%vacuum%';

2. Managing long-running transactions

Long-running transactions can cause various issues including table bloat and lock contention.

-- Find long-running transactions

SELECT pid,

usename,

application_name,

state,

query_start,

NOW() - query_start AS duration,

query

FROM pg_stat_activity

WHERE state != 'idle'

AND NOW() - query_start > interval '5 minutes'

ORDER BY duration DESC;

3. Handling deadlocks effectively

When designing applications, consider how to handle deadlocks gracefully:

-- Check deadlock history (requires pg_stat_statements extension)

SELECT substring(query, 1, 100) AS query_snippet,

calls,

total_time,

min_time,

max_time,

mean_time,

rows

FROM pg_stat_statements

WHERE query LIKE '%deadlock%'

ORDER BY total_time DESC;

4. Using advisory locks for distributed coordination

Advisory locks are perfect for implementing distributed coordination without external tools:

-- Function to attempt to acquire an advisory lock with a timeout

CREATE OR REPLACE FUNCTION try_advisory_lock(lock_id bigint, timeout_seconds int)

RETURNS boolean AS $$

DECLARE

start_time timestamp;

result boolean;

BEGIN

start_time := clock_timestamp();

LOOP

-- Try to get the lock

SELECT pg_try_advisory_lock(lock_id) INTO result;

-- If we got it, return success

IF result THEN

RETURN true;

END IF;

-- Check if we've exceeded the timeout

IF clock_timestamp() - start_time > (timeout_seconds || ' seconds')::interval THEN

RETURN false;

END IF;

-- Sleep for a bit before trying again

PERFORM pg_sleep(0.1);

END LOOP;

END;

$$ LANGUAGE plpgsql;

-- Example usage

SELECT try_advisory_lock(3001, 5); -- Try for 5 seconds

Impact of Lock Modes on Common Operations

Let’s examine how different operations are affected by locks:

1. VACUUM and concurrent operations

VACUUM (without FULL) can run concurrently with most operations:

-- Start a VACUUM

VACUUM accounts;

-- In another session, these operations should succeed:

SELECT * FROM accounts;

INSERT INTO accounts (account_number, balance) VALUES ('ACC-1006', 15000.00);

UPDATE accounts SET balance = balance * 1.05 WHERE account_id = 1;

2. CREATE INDEX and concurrent operations

Non-concurrent CREATE INDEX blocks most write operations:

-- Start a CREATE INDEX

CREATE INDEX balance_idx ON accounts(balance);

-- In another session, these operations will wait:

INSERT INTO accounts (account_number, balance) VALUES ('ACC-1007', 22000.00);

UPDATE accounts SET balance = balance * 1.10 WHERE account_id = 2;

-- But reads will succeed:

SELECT * FROM accounts;

3. CREATE INDEX CONCURRENTLY and operations

CREATE INDEX CONCURRENTLY allows most operations to continue:

-- Start a CREATE INDEX CONCURRENTLY

CREATE INDEX CONCURRENTLY account_number_idx ON accounts(account_number);

-- In another session, these operations should succeed:

SELECT * FROM accounts;

INSERT INTO accounts (account_number, balance) VALUES ('ACC-1008', 18000.00);

UPDATE accounts SET balance = balance * 1.15 WHERE account_id = 3;

Best Practices for Handling Locks

Based on our understanding of PostgreSQL locks, here are some best practices:

1. Keep transactions short

Short transactions reduce the likelihood of lock contention:

-- Instead of this:

BEGIN;

-- Do some work

-- Wait for user input or external process (potentially minutes)

-- Do more work

COMMIT;

-- Do this:

BEGIN;

-- Do all the work in one go

COMMIT;

2. Use appropriate isolation levels

Choose the right isolation level for your needs:

-- For read-only operations that don't need complete consistency:

SET TRANSACTION ISOLATION LEVEL READ COMMITTED;

-- For operations that need repeatable reads:

SET TRANSACTION ISOLATION LEVEL REPEATABLE READ;

-- For operations that need full serialization:

SET TRANSACTION ISOLATION LEVEL SERIALIZABLE;

3. Consider using FOR UPDATE SKIP LOCKED for queue-like operations

BEGIN;

-- Get the first unlocked row

SELECT * FROM task_queue

WHERE status = 'pending'

FOR UPDATE SKIP LOCKED

LIMIT 1;

-- Process the task

UPDATE task_queue SET status = 'processing' WHERE current of <cursor>;

COMMIT;

4. Monitor lock contention regularly

-- Create a view for monitoring lock contention

CREATE OR REPLACE VIEW lock_contention AS

SELECT blocked_locks.pid AS blocked_pid,

blocked_activity.usename AS blocked_user,

blocking_locks.pid AS blocking_pid,

blocking_activity.usename AS blocking_user,

blocked_activity.query AS blocked_statement,

blocking_activity.query AS blocking_statement,

blocked_activity.application_name AS blocked_application,

blocking_activity.application_name AS blocking_application,

now() - blocked_activity.xact_start AS blocked_transaction_duration,

now() - blocking_activity.xact_start AS blocking_transaction_duration

FROM pg_catalog.pg_locks blocked_locks

JOIN pg_catalog.pg_stat_activity blocked_activity ON blocked_activity.pid = blocked_locks.pid

JOIN pg_catalog.pg_locks blocking_locks

ON blocking_locks.locktype = blocked_locks.locktype

AND blocking_locks.database IS NOT DISTINCT FROM blocked_locks.database

AND blocking_locks.relation IS NOT DISTINCT FROM blocked_locks.relation

AND blocking_locks.page IS NOT DISTINCT FROM blocked_locks.page

AND blocking_locks.tuple IS NOT DISTINCT FROM blocked_locks.tuple

AND blocking_locks.virtualxid IS NOT DISTINCT FROM blocked_locks.virtualxid

AND blocking_locks.transactionid IS NOT DISTINCT FROM blocked_locks.transactionid

AND blocking_locks.classid IS NOT DISTINCT FROM blocked_locks.classid

AND blocking_locks.objid IS NOT DISTINCT FROM blocked_locks.objid

AND blocking_locks.objsubid IS NOT DISTINCT FROM blocked_locks.objsubid

AND blocking_locks.pid != blocked_locks.pid

JOIN pg_catalog.pg_stat_activity blocking_activity ON blocking_activity.pid = blocking_locks.pid

WHERE NOT blocked_locks.granted;

-- Query the view

SELECT * FROM lock_contention;

Conclusion

PostgreSQL’s locking mechanisms provide a powerful system for maintaining data consistency while maximizing concurrency. Understanding the various lock modes and their interactions is essential for building high-performance database applications.

By testing and observing lock behavior directly in PostgreSQL, we gain practical knowledge that helps us:

- Diagnose and resolve locking issues

- Design applications that handle concurrency effectively

- Optimize database performance under load

- Implement appropriate error handling for lock-related scenarios

The commands and examples in this guide provide a hands-on approach to mastering PostgreSQL locks, allowing you to apply this knowledge directly to your own database systems.

Remember that while locks are necessary for data integrity, excessive locking can lead to performance degradation. Always aim for the minimal locking strategy that meets your consistency requirements, and monitor your systems regularly for lock contention.