Technical Guide To System Calls: Implementation And Signal Handling In Modern Operating systems

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Core Definitions: Fast vs. Slow System Calls

- The Signal Interaction Mechanism

- Code Demonstration

- Gray Areas: The Case of Disk I/O

- System Call Categories in Detail

- Kernel Implementation Details

- Signal Handling in the Kernel

- Practical Applications and Best Practices

- Understanding System Call Implementation at a Lower Level

- System Call Classification in Modern Operating Systems

- The Evolution of System Call Handling

- Summary and Practical Advice

- Conclusion

Introduction

System calls are fundamental interfaces between user applications and the operating system kernel. They allow programs to request services from the operating system, such as file operations, process control, and network access. One important distinction in system calls is between “fast” and “slow” system calls, which affects how they interact with signal handling, process scheduling, and overall system performance.

In this article, we’ll explore:

- The core differences between fast and slow system calls

- The mechanism behind how signals can wake up blocked system calls

- Practical examples with code demonstrations

- How the kernel handles these different types of system calls

Core Definitions: Fast vs. Slow System Calls

Fast System Calls

Fast system calls are operations that can be completed immediately without requiring the kernel to wait for external events. They typically:

- Return quickly, usually within microseconds

- Don’t require the calling process to block or sleep

- Complete with just CPU processing time

- Don’t need to release the CPU to other processes while executing

Common examples include:

getpid(): Retrieves the process IDgettimeofday(): Gets the current timegetuid(),setuid(): Retrieves or sets user IDs- Simple memory operations like

brk()

Slow System Calls

Slow system calls are operations that may need to wait for external events or resources, potentially for an indefinite period. They typically:

- May block the calling process for an unpredictable amount of time

- Often involve waiting for I/O operations or other processes

- Cause the kernel to suspend the calling process until the operation completes

- Allow the CPU to be allocated to other processes while waiting

Common examples include:

read()from a pipe, socket, or terminal (when data isn’t immediately available)accept()waiting for network connectionswait()waiting for a child process to terminatesleep()deliberately pausing execution

The Signal Interaction Mechanism

One of the most important aspects of slow system calls is how they interact with signals, which is the mechanism you specifically asked about.

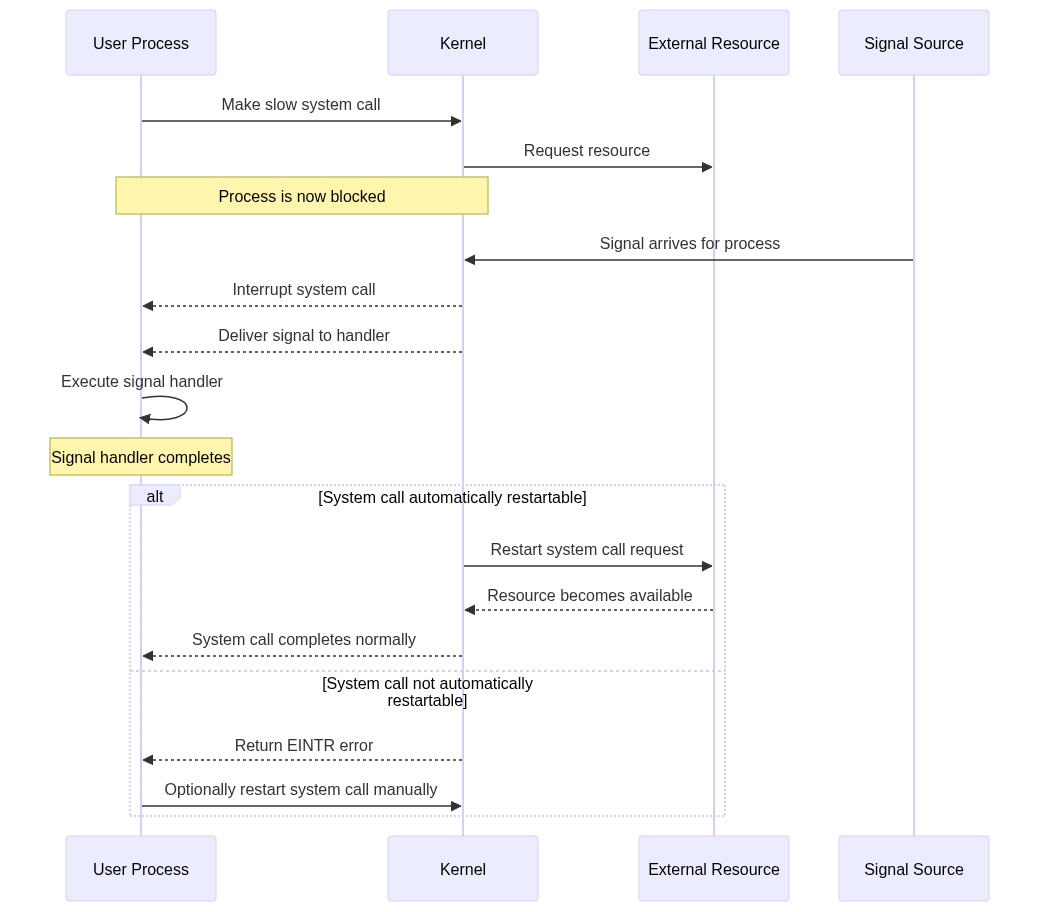

How Signals Work with Blocked System Calls

When a process is blocked in a slow system call and a signal arrives that the process has registered a handler for:

- The kernel interrupts the blocked system call

- The process returns from the system call prematurely

- The signal handler is executed

- After the signal handler completes, the system call typically returns with an error code

EINTR(Interrupted system call)

This behavior is important because it allows long-running or indefinitely blocked system calls to be interrupted, giving the process a chance to handle urgent signals.

Example Scenario

Let’s consider a typical scenario with a slow system call being interrupted by a signal:

- A process calls

read()on a socket with no data available - The process is put to sleep by the kernel (blocked)

- While blocked, a

SIGALRMsignal arrives (perhaps from a timer) - The kernel interrupts the

read()system call - The registered signal handler for

SIGALRMexecutes - After the handler completes, the

read()call returns with-1anderrnoset toEINTR - The application code can check for this error and decide whether to restart the system call

Code Demonstration

Let’s implement a practical example showing how a slow system call (read() from a pipe) interacts with signal handling. This will help clarify the mechanism.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <signal.h>

#include <errno.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <fcntl.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <sys/wait.h>

#include <time.h>

// Global flag to track if a signal was received

volatile sig_atomic_t signal_received = 0;

// Counter to track how many signals have been received

volatile sig_atomic_t signal_count = 0;

// Signal handler for SIGALRM

void signal_handler(int signum) {

signal_received = 1;

signal_count++;

printf("\n[Signal Handler] Received signal %d. Count: %d\n", signum, signal_count);

}

int main() {

int pipefd[2];

char buf[100];

ssize_t bytes_read;

// Create a pipe

if (pipe(pipefd) == -1) {

perror("pipe");

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

// Set up signal handler for SIGALRM

struct sigaction sa;

memset(&sa, 0, sizeof(sa));

sa.sa_handler = signal_handler;

// Using SA_RESTART would make some system calls restart automatically

// We're intentionally not using it to demonstrate EINTR

sa.sa_flags = 0;

sigaction(SIGALRM, &sa, NULL);

printf("Setting up an alarm to trigger in 2 seconds...\n");

printf("Will attempt to read from an empty pipe (this will block)...\n");

// Set alarm to trigger in 2 seconds

alarm(2);

// Try to read from the pipe - this is a slow system call

// that will block until data is available or a signal occurs

printf("\nAttempting read at time: %ld\n", time(NULL));

bytes_read = read(pipefd[0], buf, sizeof(buf));

printf("Read call returned at time: %ld\n", time(NULL));

if (bytes_read == -1) {

if (errno == EINTR) {

printf("\n[Main] Read was interrupted by signal! (EINTR)\n");

} else {

perror("read");

}

} else {

printf("Read %zd bytes\n", bytes_read);

}

printf("\nDemonstrating restartable read...\n");

// Set another alarm

signal_received = 0;

alarm(2);

// Try to read again, but this time manually restart if interrupted

int restart_count = 0;

do {

printf("\nAttempting read (try #%d) at time: %ld\n",

restart_count+1, time(NULL));

bytes_read = read(pipefd[0], buf, sizeof(buf));

if (bytes_read == -1 && errno == EINTR) {

restart_count++;

printf("[Main] Read was interrupted by signal! Restarting...\n");

}

} while (bytes_read == -1 && errno == EINTR && restart_count < 3);

printf("Final read returned at time: %ld with result: %zd\n",

time(NULL), bytes_read);

if (bytes_read == -1) {

printf("Error: %s\n", strerror(errno));

}

// Clean up

close(pipefd[0]);

close(pipefd[1]);

printf("\nNow demonstrating a fast system call...\n");

alarm(2);

// Get process ID - this is a fast system call that won't block

pid_t pid = getpid();

if (signal_received) {

printf("Signal was received during or after getpid(), but getpid() completed anyway\n");

} else {

printf("getpid() completed before signal was received\n");

}

printf("Process ID: %d\n", pid);

return 0;

}

How to Compile and Run the Code

To compile and run this code example:

gcc -o syscall_demo syscall_demo.c

./syscall_demo

Expected Output

Here’s what you can expect to see when running the program:

Setting up an alarm to trigger in 2 seconds...

Will attempt to read from an empty pipe (this will block)...

Attempting read at time: 1711805420

[Signal Handler] Received signal 14. Count: 1

Read call returned at time: 1711805422

[Main] Read was interrupted by signal! (EINTR)

Demonstrating restartable read...

Attempting read (try #1) at time: 1711805422

[Signal Handler] Received signal 14. Count: 2

[Main] Read was interrupted by signal! Restarting...

Attempting read (try #2) at time: 1711805424

[Main] Read was interrupted by signal! Restarting...

Attempting read (try #3) at time: 1711805424

Final read returned at time: 1711805424 with result: -1

Error: Resource temporarily unavailable

Now demonstrating a fast system call...

Signal was received during or after getpid(), but getpid() completed anyway

Process ID: 12345

Understanding the Output

- In the first part, the program sets up a SIGALRM to trigger after 2 seconds while attempting to read from an empty pipe.

- The read operation blocks, and when the alarm triggers, the signal handler is executed.

- After the signal handler completes, the read call returns with an EINTR error.

- In the second part, we demonstrate manually restarting the interrupted system call.

- Finally, we demonstrate a fast system call (getpid) that completes regardless of signal delivery.

Gray Areas: The Case of Disk I/O

As mentioned in the reference answer, there are some gray areas between fast and slow system calls. Reading from a disk file with read() is an interesting case:

- From the user’s perspective, disk reads are usually considered non-blocking because they typically complete quickly.

- From the kernel’s perspective, disk reads are slow system calls because the process must wait for the disk driver to complete the operation.

Let’s see how the kernel handles this with a practical example:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <signal.h>

#include <errno.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <fcntl.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <time.h>

volatile sig_atomic_t signal_received = 0;

volatile sig_atomic_t signal_count = 0;

void signal_handler(int signum) {

signal_received = 1;

signal_count++;

printf("\n[Signal Handler] Received signal %d. Count: %d\n", signum, signal_count);

}

int main() {

// Create a large temporary file

const char *filename = "large_temp_file.dat";

int fd;

const size_t file_size = 100 * 1024 * 1024; // 100 MB

char buffer[4096];

// Set up signal handler

struct sigaction sa;

memset(&sa, 0, sizeof(sa));

sa.sa_handler = signal_handler;

sa.sa_flags = 0; // Don't use SA_RESTART

sigaction(SIGALRM, &sa, NULL);

// Create a large temporary file for testing

printf("Creating a large temporary file (%zu MB)...\n", file_size / (1024 * 1024));

fd = open(filename, O_WRONLY | O_CREAT | O_TRUNC, 0644);

if (fd == -1) {

perror("open for writing");

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

// Fill with random data

memset(buffer, 'A', sizeof(buffer));

size_t total_written = 0;

while (total_written < file_size) {

ssize_t written = write(fd, buffer, sizeof(buffer));

if (written == -1) {

perror("write");

close(fd);

unlink(filename);

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

total_written += written;

// Show progress

if (total_written % (10 * 1024 * 1024) == 0) {

printf(".");

fflush(stdout);

}

}

printf("\nFile created.\n");

close(fd);

// Now open the file for reading

fd = open(filename, O_RDONLY);

if (fd == -1) {

perror("open for reading");

unlink(filename);

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

// First, read a small chunk normally

printf("\nReading a small chunk first...\n");

if (read(fd, buffer, sizeof(buffer)) == -1) {

perror("read small chunk");

}

// Seek to a random position in the file

off_t random_pos = rand() % (file_size - sizeof(buffer));

if (lseek(fd, random_pos, SEEK_SET) == -1) {

perror("lseek");

}

printf("\nWill now attempt a large disk read operation with signal...\n");

printf("Setting alarm for 0.1 seconds...\n");

// Schedule alarm to trigger during read

alarm(1); // 1 second

// Force sync to flush caches, making the next read slower

sync();

// Try to read a large chunk - this may or may not block long enough

time_t start_time = time(NULL);

printf("Starting read at time: %ld\n", start_time);

// Read the entire file sequentially to increase likelihood of blocking

total_written = 0;

int interrupted = 0;

while (total_written < file_size) {

ssize_t bytes_read = read(fd, buffer, sizeof(buffer));

if (bytes_read == -1) {

if (errno == EINTR) {

printf("\n[Main] Read was interrupted by signal! (EINTR)\n");

interrupted = 1;

break;

} else {

perror("read large chunk");

break;

}

} else if (bytes_read == 0) {

// End of file

break;

}

total_written += bytes_read;

}

time_t end_time = time(NULL);

printf("Read operation finished at time: %ld (took %ld seconds)\n",

end_time, end_time - start_time);

if (!interrupted) {

if (signal_received) {

printf("Signal was received but read was NOT interrupted!\n");

printf("This demonstrates that disk reads may complete despite signals.\n");

} else {

printf("Signal was not received or read completed too quickly.\n");

}

}

// Clean up

close(fd);

unlink(filename);

return 0;

}

How to Compile and Run the Disk I/O Example

gcc -o disk_io_demo disk_io_demo.c

./disk_io_demo

Expected Output for Disk I/O Example

The output may vary depending on your system’s disk speed and caching, but should look something like this:

Creating a large temporary file (100 MB)...

..........

File created.

Reading a small chunk first...

Will now attempt a large disk read operation with signal...

Setting alarm for 0.1 seconds...

Starting read at time: 1711805430

[Signal Handler] Received signal 14. Count: 1

Signal was received but read was NOT interrupted!

This demonstrates that disk reads may complete despite signals.

Read operation finished at time: 1711805431 (took 1 seconds)

Understanding the Disk I/O Results

This example shows a key point about disk reads:

- Even though disk reads are technically “slow” system calls from the kernel’s perspective, they often complete quickly enough that the signal doesn’t interrupt them.

- Modern operating systems implement sophisticated caching and I/O scheduling that make disk reads faster.

- Some systems may implement disk reads in a way that doesn’t allow them to be interrupted by signals.

System Call Categories in Detail

Let’s explore the three gradations of system calls mentioned in the reference answer:

1. Non-blocking System Calls (Fast)

These system calls return immediately, only requiring CPU time. They include:

- Information retrieval:

getpid(),getuid(),gettimeofday() - Simple state changes:

setuid(),umask() - Memory operations:

brk(),sbrk() - Simple file operations on already-cached data

- Operations on already-available kernel data structures

2. Potentially Blocking System Calls (Medium)

These can take a while to complete but have a maximum duration:

sleep(),nanosleep(): Timer-based pausesalarm(): Setting up a future signal- Most file system metadata operations:

stat(),access() - Simple network operations with timeouts

- Disk I/O operations (as discussed in the gray area)

3. Indefinitely Blocking System Calls (Slow)

These don’t return until an external event occurs:

read()from pipes, terminals, or sockets with no datawrite()to full pipes or blocked socketsaccept()waiting for network connectionsconnect()establishing network connectionswait()waiting for child processespause()waiting indefinitely for a signalselect(),poll(),epoll_wait()waiting for I/O events

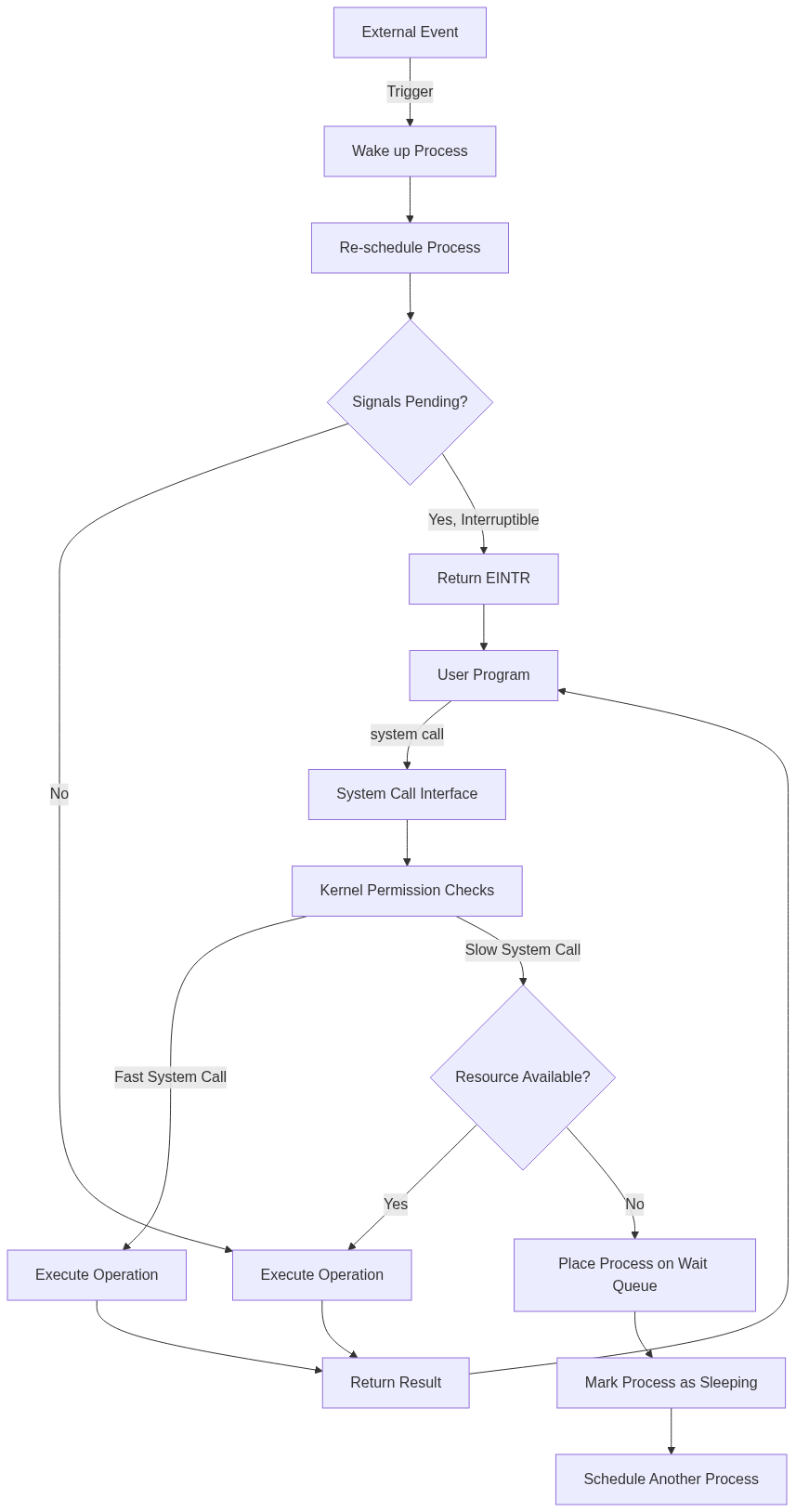

Kernel Implementation Details

To fully understand the differences between fast and slow system calls, let’s look at how the kernel implements them.

Fast System Call Implementation

Fast system calls are implemented with a straightforward approach:

- User code invokes the system call using the appropriate architecture-specific mechanism (e.g.,

syscallinstruction). - The kernel validates arguments and performs permission checks.

- The kernel executes the requested operation directly in the context of the calling process.

- The kernel returns the result to user space.

- The process continues execution.

In this process, the calling thread never relinquishes the CPU, and the system call handler completes without scheduling other tasks.

Slow System Call Implementation

Slow system calls have a more complex implementation:

- User code invokes the system call.

- The kernel validates arguments and performs permission checks.

- If the requested resource/event is unavailable, the kernel: a. Places the process on a wait queue for the resource/event b. Marks the process as being in an interruptible or uninterruptible sleep state c. Invokes the scheduler to select another process to run

- When the event occurs (e.g., data arrives on a socket): a. The kernel marks the waiting process as runnable b. The scheduler eventually selects the process to run again c. The system call handler continues execution

- Before returning to user space, the kernel checks if signals arrived during the wait:

a. If signals are pending and the wait was interruptible, the call returns

EINTRb. Otherwise, the call completes normally

Signal Handling in the Kernel

Understanding how the kernel handles signals is crucial to understanding the interaction with slow system calls:

- When a signal is generated (by another process or the kernel itself), the kernel sets a bit in the target process’s signal pending bitmap.

- Before returning to user space from a system call or interrupt, the kernel checks if any signals are pending for the current process.

- If there are pending signals and the process has registered a handler, the kernel:

a. If the process is blocked in an interruptible system call, wakes up the process

b. Sets up the user stack to execute the signal handler

c. When the handler completes, either restarts the system call or returns with

EINTR

Automatic System Call Restart

Modern UNIX-like systems provide a mechanism to automatically restart certain system calls when interrupted by signals. This is controlled by the SA_RESTART flag when registering signal handlers with sigaction().

When SA_RESTART is set:

- The kernel automatically restarts compatible system calls after the signal handler returns

- The program doesn’t need to handle

EINTRerrors explicitly

When SA_RESTART is not set:

- System calls return with

EINTRwhen interrupted by signals - The program must handle this error and decide whether to restart the call

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <signal.h>

#include <errno.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <fcntl.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <time.h>

volatile sig_atomic_t signal_received = 0;

void signal_handler(int signum) {

signal_received = 1;

printf("\n[Signal Handler] Received signal %d\n", signum);

sleep(1); // Sleep to make the handler take a noticeable amount of time

}

int main() {

int pipefd[2];

char buf[100];

ssize_t bytes_read;

// Create a pipe

if (pipe(pipefd) == -1) {

perror("pipe");

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

printf("Test 1: Without SA_RESTART\n");

// Set up signal handler without SA_RESTART

struct sigaction sa_no_restart;

memset(&sa_no_restart, 0, sizeof(sa_no_restart));

sa_no_restart.sa_handler = signal_handler;

sa_no_restart.sa_flags = 0; // No SA_RESTART flag

sigaction(SIGALRM, &sa_no_restart, NULL);

printf("Reading from empty pipe with alarm (no SA_RESTART)...\n");

alarm(2);

time_t start_time = time(NULL);

printf("Starting read at time: %ld\n", start_time);

bytes_read = read(pipefd[0], buf, sizeof(buf));

time_t end_time = time(NULL);

printf("Read returned at time: %ld (took %ld seconds)\n",

end_time, end_time - start_time);

if (bytes_read == -1) {

if (errno == EINTR) {

printf("[Main] Read was interrupted by signal (EINTR)\n");

} else {

perror("read");

}

}

// Reset for next test

signal_received = 0;

printf("\nTest 2: With SA_RESTART\n");

// Set up signal handler with SA_RESTART

struct sigaction sa_restart;

memset(&sa_restart, 0, sizeof(sa_restart));

sa_restart.sa_handler = signal_handler;

sa_restart.sa_flags = SA_RESTART; // Use SA_RESTART flag

sigaction(SIGALRM, &sa_restart, NULL);

printf("Reading from empty pipe with alarm (with SA_RESTART)...\n");

alarm(2);

start_time = time(NULL);

printf("Starting read at time: %ld\n", start_time);

bytes_read = read(pipefd[0], buf, sizeof(buf));

end_time = time(NULL);

printf("Read returned at time: %ld (took %ld seconds)\n",

end_time, end_time - start_time);

if (bytes_read == -1) {

if (errno == EINTR) {

printf("[Main] Read was interrupted by signal (EINTR)\n");

} else {

perror("read");

}

} else {

printf("Unexpected: read returned data\n");

}

// Clean up

close(pipefd[0]);

close(pipefd[1]);

return 0;

}

How to Compile and Run the SA_RESTART Example

gcc -o restart_demo restart_demo.c

./restart_demo

Expected Output for SA_RESTART Example

Test 1: Without SA_RESTART

Reading from empty pipe with alarm (no SA_RESTART)...

Starting read at time: 1711805440

[Signal Handler] Received signal 14

Read returned at time: 1711805443 (took 3 seconds)

[Main] Read was interrupted by signal (EINTR)

Test 2: With SA_RESTART

Reading from empty pipe with alarm (with SA_RESTART)...

Starting read at time: 1711805443

[Signal Handler] Received signal 14

Note that in the second test with SA_RESTART, the read operation doesn’t return after the signal handler completes but continues blocking. In a real-world program, you’d need another mechanism to terminate the second read (such as a second alarm or another process writing to the pipe).

Practical Applications and Best Practices

Understanding the distinction between fast and slow system calls has practical implications for software design:

1. Signal Handler Design

When designing signal handlers, consider:

- Keep signal handlers minimal and async-signal-safe

- Use volatile sig_atomic_t for flags modified in signal handlers

- Decide carefully whether to use SA_RESTART based on your application needs

2. Handling EINTR

For robust code, always check for EINTR when using slow system calls:

/* EINTR-safe read function */

ssize_t safe_read(int fd, void *buf, size_t count) {

ssize_t result;

do {

result = read(fd, buf, count);

} while (result == -1 && errno == EINTR);

return result;

}

/* EINTR-safe write function */

ssize_t safe_write(int fd, const void *buf, size_t count) {

ssize_t result;

size_t bytes_written = 0;

while (bytes_written < count) {

result = write(fd, (const char*)buf + bytes_written, count - bytes_written);

if (result == -1) {

if (errno == EINTR)

continue; // Try again

return -1; // Real error

}

if (result == 0)

break; // Can't write any more

bytes_written += result;

}

return bytes_written;

}

/* EINTR-safe wait function */

pid_t safe_wait(int *wstatus) {

pid_t result;

do {

result = wait(wstatus);

} while (result == -1 && errno == EINTR);

return result;

}

3. Using Non-blocking I/O

For responsive applications, consider using non-blocking I/O with polling:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <fcntl.h>

#include <errno.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <poll.h>

int main() {

int pipefd[2];

char buf[100];

ssize_t bytes_read;

// Create a pipe

if (pipe(pipefd) == -1) {

perror("pipe");

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

// Set read end to non-blocking

int flags = fcntl(pipefd[0], F_GETFL, 0);

fcntl(pipefd[0], F_SETFL, flags | O_NONBLOCK);

// Try to read from empty pipe (non-blocking)

printf("Attempting non-blocking read from empty pipe...\n");

bytes_read = read(pipefd[0], buf, sizeof(buf));

if (bytes_read == -1) {

if (errno == EAGAIN || errno == EWOULDBLOCK) {

printf("No data available (EAGAIN/EWOULDBLOCK) - would have blocked\n");

} else {

perror("read");

}

} else {

printf("Read %zd bytes\n", bytes_read);

}

// Now use poll to wait for data with timeout

printf("\nNow using poll() to wait for data with 3-second timeout...\n");

struct pollfd fds[1];

fds[0].fd = pipefd[0];

fds[0].events = POLLIN;

int poll_result = poll(fds, 1, 3000); // 3 second timeout

if (poll_result == -1) {

perror("poll");

} else if (poll_result == 0) {

printf("Poll timed out after 3 seconds\n");

} else {

if (fds[0].revents & POLLIN) {

printf("Data is available for reading!\n");

bytes_read = read(pipefd[0], buf, sizeof(buf));

if (bytes_read == -1) {

perror("read after poll");

} else {

printf("Read %zd bytes\n", bytes_read);

}

}

}

// Clean up

close(pipefd[0]);

close(pipefd[1]);

return 0;

}

4. Using Asynchronous I/O

For highly concurrent applications, asynchronous I/O allows operations to complete without blocking:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <fcntl.h>

#include <errno.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <aio.h>

#include <signal.h>

#include <time.h>

#define BUFFER_SIZE 4096

volatile sig_atomic_t aio_complete = 0;

// Signal handler for AIO completion

void aio_completion_handler(int signo, siginfo_t *info, void *context) {

if (info->si_signo == SIGRTMIN) {

aio_complete = 1;

printf("\n[AIO Handler] Asynchronous I/O operation completed\n");

}

}

int main() {

int fd;

struct aiocb my_aiocb;

struct sigaction sa;

char *buffer;

// Allocate a buffer

buffer = malloc(BUFFER_SIZE);

if (buffer == NULL) {

perror("malloc");

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

// Open a file for reading

fd = open("/etc/passwd", O_RDONLY);

if (fd == -1) {

perror("open");

free(buffer);

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

// Set up the AIO request

memset(&my_aiocb, 0, sizeof(struct aiocb));

my_aiocb.aio_fildes = fd;

my_aiocb.aio_buf = buffer;

my_aiocb.aio_nbytes = BUFFER_SIZE;

my_aiocb.aio_offset = 0;

// Set up the signal handler for AIO completion

memset(&sa, 0, sizeof(sa));

sa.sa_flags = SA_SIGINFO;

sa.sa_sigaction = aio_completion_handler;

sigemptyset(&sa.sa_mask);

sigaction(SIGRTMIN, &sa, NULL);

// Set up the AIO control block

my_aiocb.aio_sigevent.sigev_notify = SIGEV_SIGNAL;

my_aiocb.aio_sigevent.sigev_signo = SIGRTMIN;

// Initiate asynchronous read

printf("Starting asynchronous read operation...\n");

if (aio_read(&my_aiocb) == -1) {

perror("aio_read");

close(fd);

free(buffer);

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

// Main program can continue doing other work

printf("Asynchronous read initiated. Main program continues...\n");

// Simulate doing other work

int i;

for (i = 0; i < 3; i++) {

printf("Main program: Doing other work... (%d/3)\n", i+1);

sleep(1);

}

// Check if AIO has completed

if (aio_complete) {

printf("AIO completed via signal notification\n");

} else {

printf("AIO hasn't completed yet, waiting for completion...\n");

// Wait for completion if not already done

const struct aiocb *aiocb_list[1] = {&my_aiocb};

aio_suspend(aiocb_list, 1, NULL);

printf("AIO completed via aio_suspend\n");

}

// Check the status

int ret = aio_error(&my_aiocb);

if (ret) {

if (ret == EINPROGRESS) {

printf("Operation still in progress\n");

} else {

fprintf(stderr, "AIO error: %s\n", strerror(ret));

}

} else {

// Get the return status

ssize_t bytes_read = aio_return(&my_aiocb);

printf("Read completed successfully with %zd bytes\n", bytes_read);

// Print the first few bytes of data

if (bytes_read > 0) {

buffer[bytes_read < 50 ? bytes_read : 50] = '\0';

printf("First bytes: %.50s...\n", buffer);

}

}

// Clean up

close(fd);

free(buffer);

return 0;

}

Understanding System Call Implementation at a Lower Level

To gain an even deeper understanding of how the kernel differentiates between fast and slow system calls, let’s examine a simplified implementation of both types.

Fast System Call: getpid()

/* Simplified implementation of getpid() system call in the Linux kernel */

SYSCALL_DEFINE0(getpid)

{

/* Simply return the process ID from the current task structure */

return task_tgid_vnr(current);

}

This is a very simple implementation that just returns the current process ID from the task structure. There’s no need to block or wait for anything.

Slow System Call: read()

/* Simplified implementation of read() system call in the Linux kernel */

SYSCALL_DEFINE3(read, unsigned int, fd, char __user *, buf, size_t, count)

{

struct file *file;

ssize_t ret = -EBADF;

/* Get the file structure for this file descriptor */

file = fget(fd);

if (!file)

return ret;

/* Verify user buffer is valid */

if (!access_ok(buf, count)) {

ret = -EFAULT;

goto out;

}

/* Call the file's read operation */

ret = vfs_read(file, buf, count, &file->f_pos);

out:

fput(file);

return ret;

}

/* Inside vfs_read for a pipe or socket */

static ssize_t pipe_read(struct file *file, char __user *buf, size_t count, loff_t *ppos)

{

struct pipe_inode_info *pipe = file->private_data;

ssize_t ret;

/* Lock the pipe */

mutex_lock(&pipe->mutex);

/* If pipe is empty and not O_NONBLOCK, wait for data */

while (pipe_empty(pipe)) {

/* If non-blocking, return immediately */

if (file->f_flags & O_NONBLOCK) {

ret = -EAGAIN;

goto out;

}

/* Release lock and prepare to sleep */

mutex_unlock(&pipe->mutex);

/* Wait on the pipe's wait queue */

ret = wait_event_interruptible(pipe->wait, !pipe_empty(pipe));

/* If we were interrupted by a signal */

if (ret)

return ret; /* Returns -ERESTARTSYS or -EINTR */

/* Reacquire the lock */

mutex_lock(&pipe->mutex);

}

/* Now data is available, copy it to user space */

ret = pipe_do_read(pipe, buf, count);

out:

mutex_unlock(&pipe->mutex);

return ret;

}

This simplified implementation shows the key differences:

getpid()simply accesses data already in memory and returns immediately.read()must:- Check if data is available

- If no data is available and O_NONBLOCK is not set, put the process to sleep

- Wake up when data becomes available or a signal arrives

- Check for signals that might have interrupted the wait

- Finally, perform the read operation

System Call Classification in Modern Operating Systems

Modern operating systems have evolved to include more nuanced categories of system calls:

1. Fully Synchronous (Fast) System Calls

These execute entirely within the context of the calling process:

- Information retrieval (

getpid,getuid) - Simple state changes (

setuid) - Memory operations (

brk)

2. Asynchronous System Calls

These start an operation but return immediately:

aio_read,aio_write(POSIX AIO)io_submit(Linux AIO)sendwith MSG_DONTWAIT flag

3. Blocking with Timeout System Calls

These block but have a maximum wait time:

poll,select,epoll_waitwith timeoutrecvwith timeoutsem_timedwait

4. Indefinitely Blocking System Calls

These may block indefinitely:

readwithout O_NONBLOCKaccepton a listening socketwaitfor a child process

5. Restartable System Calls

These can be automatically restarted after signal handling:

- Most blocking system calls with SA_RESTART flag

The Evolution of System Call Handling

Over time, operating systems have evolved more sophisticated mechanisms for handling system calls:

1. Traditional Blocking I/O

The oldest approach simply blocks threads until operations complete.

2. Non-blocking I/O with Polling

Allows a thread to check for readiness without blocking.

3. I/O Multiplexing

Enables a single thread to monitor multiple file descriptors:

select(),poll(),epoll()- Efficient for handling many connections

4. Signal-Driven I/O

Uses signals to notify when I/O is possible:

SIGIOsignal indicates I/O readiness- Can be used with

F_SETSIGfcntl

5. Asynchronous I/O

Allows operations to complete in the background:

- POSIX AIO (

aio_*functions) - Linux-specific AIO (

io_*functions)

6. I/O Uring (Linux)

The newest approach combining the best features:

- Submission and completion queues

- Batched operations

- Minimized system call overhead

graph TB

A[Traditional Blocking I/O] -->|Add O_NONBLOCK| B[Non-blocking I/O]

B -->|Centralize monitoring| C[I/O Multiplexing]

C -->|Add notifications| D[Signal-Driven I/O]

D -->|Background completion| E[Asynchronous I/O]

E -->|Optimize for performance| F[I/O Uring]

subgraph "Blocking Paradigm"

A

end

subgraph "Non-Blocking Paradigm"

B

C

D

end

subgraph "Asynchronous Paradigm"

E

F

end

style A fill:#FFEEEE

style B fill:#EEEEFF

style C fill:#EEEEFF

style D fill:#EEEEFF

style E fill:#EEFFEE

style F fill:#EEFFEE

Summary and Practical Advice

To summarize the key differences between fast and slow system calls:

Fast System Calls:

- Return immediately with just CPU time

- Don’t block the calling process

- Can’t be interrupted by signals

- Examples:

getpid(),gettimeofday(),getuid()

Slow System Calls:

- May block indefinitely waiting for external events

- Allow the CPU to be used by other processes while waiting

- Can be interrupted by signals, returning

EINTR - Examples:

read()from pipes/sockets,accept(),wait()

Best Practices:

- Handle EINTR properly: Always check for and handle

EINTRreturns from slow system calls - Use SA_RESTART when appropriate: For simplicity, consider using

SA_RESTARTwhen registering signal handlers - Consider non-blocking I/O: For responsive applications, non-blocking I/O with

select()/poll()/epoll()can be more efficient - Use the right tool for the job: Match your I/O paradigm to your application’s needs:

- Simple sequential operations: Blocking I/O

- Interactive applications: Non-blocking with polling

- High-performance servers: I/O multiplexing or asynchronous I/O

By understanding the differences between fast and slow system calls and how they interact with signals, you can write more robust and efficient systems software.

Conclusion

The distinction between fast and slow system calls is fundamental to understanding how operating systems handle process scheduling, signal delivery, and I/O operations. While the terminology might vary (non-blocking vs. blocking, fast vs. slow), the underlying concepts remain consistent across UNIX-like operating systems.

Modern operating systems have evolved sophisticated mechanisms for dealing with different types of system calls, from simple fast calls to complex asynchronous operations. Understanding these mechanisms is essential for developing robust, high-performance applications that interact with the operating system efficiently.

By properly handling signal interruptions, choosing appropriate I/O models, and understanding the implementation details of system calls, programmers can write more reliable and efficient code that gracefully handles the complex interactions between processes, signals, and the kernel.